Seattle critic Elizabeth Bryant tends to write about art at the margins of the Seattle experience. If she were in New York or LA, she’d find the less likely there too. Ditto North Dakota. Whatever is central in North Dakota would be unlikely to move her, but a North Dakota follower of Italian Futurism who paints in a sagging house off a rutted road and fails to notice that Futurism is a century past its pull date might well become the subject of her illuminated scrutiny.

Here she is on painter David Kane:

“Farewell to Mars and Other Paintings” is Kane’s first show “since all that happened,” (meaning his diagnosis, treatment, and recovery from lung and thyroid cancer…) Some of the canvases in the show were begun ten years ago, set aside and picked up again; others are entirely new. Allusions to the battle with cancer can be read throughout the show in saucers, moons and suns that look like cells, in the scorched earth and the struggle of flesh and technology.

In “Farewell to Mars”, a priapic alien herma gives a three-fingered wave to a trio of flying saucers soaring like so many platelets in the purple skies of a red planet. It’s a hopeful sign.

Kane’s painting, as always, is intellectually and pictorially brilliant, going far beyond the personal. He plays with spatial recession, atmospheric effects, and deceptively tight compositions, pulling from 18th-century Venetian vedute painters (think Canaletto), depression-era regionalism (think Benton and Hopper), ’50s pulp sci-fi illustration, and apocalyptic fundamentalist religious tracts (rapture merges with alien abduction) to reference classical myth and rationalism, post-war atomic-age conformity, environmental disaster, and the war-ravaged sands of the Middle East. (more)

Canaletto? Not even a little bit. I can see Benton without the rhythm and Hopper without the light, however. Kane’s paintings look as if he made them with caked powders on sandpaper. In their choked aridities, in their coarse forms and muddy colors, there is something genuine, a real toad in his imaginary garden. Bryant is thunderously wrong in what she sees in him, but I enjoyed reading every word. She’s that rare critic who lives not because of her judgments but in spite of them.

Canaletto? Not even a little bit. I can see Benton without the rhythm and Hopper without the light, however. Kane’s paintings look as if he made them with caked powders on sandpaper. In their choked aridities, in their coarse forms and muddy colors, there is something genuine, a real toad in his imaginary garden. Bryant is thunderously wrong in what she sees in him, but I enjoyed reading every word. She’s that rare critic who lives not because of her judgments but in spite of them.

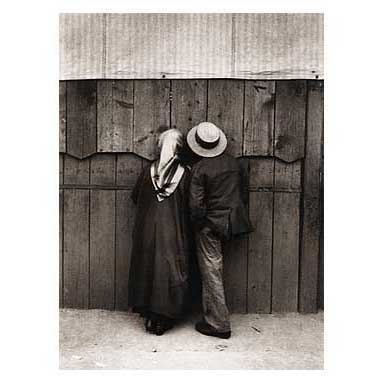

The photos reveal different aspects of the character: the modest concrete and the marquee.

The photos reveal different aspects of the character: the modest concrete and the marquee.

Through Dec. 19.

Through Dec. 19.

From

From On Facebook,

On Facebook,

I’m not sure if the piece passed the Woody Allen test. Allen hates lawns too. Nevertheless, Kelly continues to define her position. From 2009, No Tofu, No Yoga Matt.

I’m not sure if the piece passed the Woody Allen test. Allen hates lawns too. Nevertheless, Kelly continues to define her position. From 2009, No Tofu, No Yoga Matt.