One step up from a Cracker Jack toy, Diana cameras entered the U.S. market from China in the late 1950s and were a novelty hit through the 1960s.

The Diana is a very simply constructed box camera with a mechanical film

advance, spring-loaded shutter, and a plastic viewfinder of

questionable utility. It is constructed primarily of low-quality

phenolic plastics of the type commonly found in toys imported from Asia

during the 1960s. Because of wide variances in production quality,

combined with a poorly-designed camera body latching mechanism, Diana

cameras are predisposed to light leaks onto the exposed film.

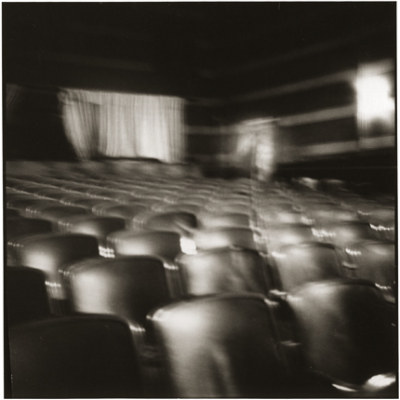

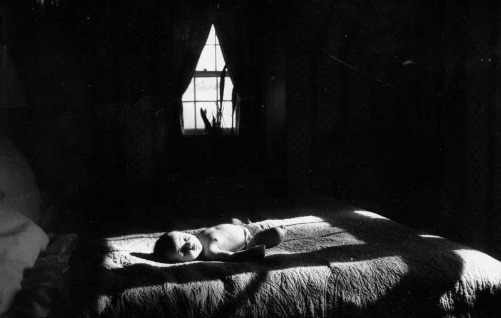

In the 1970s, riding on a river of chance, Nancy Rexroth began to make the most of the camera’s unpredictable disadvantages. (1975, 8 x10 inches, vintage silver print)

Rexroth:

Rexroth:

Diana images are often something you might see faintly in the background

of a photograph… sometimes, I feel I could step over the edge of a

frame and walk backwards into this unknown region. Then I would keep

right on walking…

Her figures are standing there, but they’re already gone.

Amy Blakemore began using the Diana in graduate school in the 1980s at the University of Texas. Unlike Rexroth, who stuck to black and white, Blakemore quickly switched to color. And while Rexroth’s prints are otherworldly, related to late 19th Century Pictorialism, Blakemore’s have an internal precision inside the blur.

For her, clicking the shutter produces a rough draft. What’s important about her prints she achieves in the darkroom. There is nothing accidental about her compositions or her tonal orchestration. And while Rexroth’s landscapes and figures fragile, shot full of light, Blakemore’s are oddly sturdy. She makes them by hand, and her constructions favor the solid. One more thing: While Rexroth’s is a silent world, Blakemore’s tends toward the convivial. Her figures frequently face the camera and look as if they are about to greet the viewer.

Steph, 1995

A 20-year survey of her work is at the Seattle Art Museum courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, curated by Alison de Lima Greene. At James Harris Gallery is a selection of recent work.

A 20-year survey of her work is at the Seattle Art Museum courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, curated by Alison de Lima Greene. At James Harris Gallery is a selection of recent work.

Green’s show is gorgeous, but its installation at SAM is a problem. The problem isn’t necessarily the corridor where it hangs. That particular corridor worked well for Everything Under The Sun: Photographs of Imogen Cunningham and the lovely little Tack & Jibe, art about sailing. But Blakemore’s photos look as if they’re still in storage. Why paid pay to ship 40 framed photos, take them out of a box and put them in another box? They need more room to breath, and so does the viewer.

Blakemore deserves more and gets it at James Harris – small gallery in the back but well-lit, well-hung and not crowded.

I love her historical resonance. Take, for instance, W. Eugene Smith’s A Walk To Paradise Garden, 1946.

Blakemore strips the image of its sentimentality, its holy hush. She lights the before of the passage as well as the after and lays a whip strap of a shadow across the boy’s back.

Blakemore strips the image of its sentimentality, its holy hush. She lights the before of the passage as well as the after and lays a whip strap of a shadow across the boy’s back.

Boy in Woods, 2010

Chromogenic Print Ed. of 10

19″ x 19″

A shadow expands to cover most of her mother’s stoic face but everything is visible inside it. The composition centers on a tension-release narrative, as the hands of the man holding the wheelchair are white along their edges. (Although he’s the one driving her into the dark, she’s ready and he’s not.)

A shadow expands to cover most of her mother’s stoic face but everything is visible inside it. The composition centers on a tension-release narrative, as the hands of the man holding the wheelchair are white along their edges. (Although he’s the one driving her into the dark, she’s ready and he’s not.)

Mom, 2009

Chromogenic Print Ed. of 10

19″ x 19″

In spirit, her work is closest to Neil Goldberg‘s.

In spirit, her work is closest to Neil Goldberg‘s.

Goldberg, My Father Breathing into a Mirror

Single channel video

2005

1:00 min

Silent

Both Blakemore and Goldberg relate to the final lines of John Cheever’s Falconer:

Both Blakemore and Goldberg relate to the final lines of John Cheever’s Falconer:

Farragut walked to the front of the bus and got off at the next stop.

Stepping onto the street he saw he had lost his fear of falling (he had

forgotten how to walk as a free man). He held his head high, his back

straight and walked along nicely. Rejoice, he thought. Rejoice.

Blakemore through Feb. 13 at SAM; through Oct. 9 at James Harris.

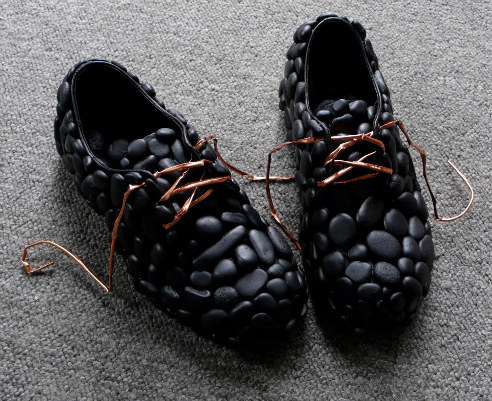

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals ( I also like the hat, via

I also like the hat, via

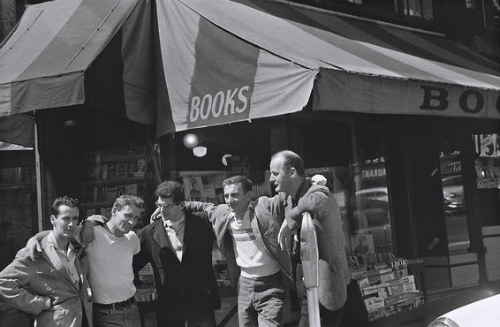

When was it taken? In

When was it taken? In  Standing in the parking lot, we’re sitting on the edge of our imaginary seats. As befits everyone’s busy schedule, we enjoy the beginning and end without having to suffer through the middle. The curtain offers what

Standing in the parking lot, we’re sitting on the edge of our imaginary seats. As befits everyone’s busy schedule, we enjoy the beginning and end without having to suffer through the middle. The curtain offers what  In the video gallery,

In the video gallery,  About that light going on and off (Work No. 227) –

About that light going on and off (Work No. 227) –  By solitude:

By solitude: By force:

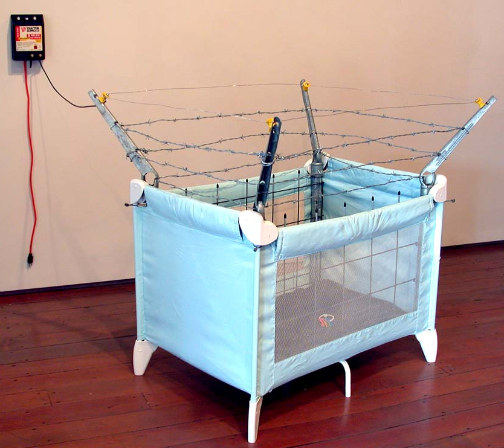

By force: By restriction:

By restriction: By projection:

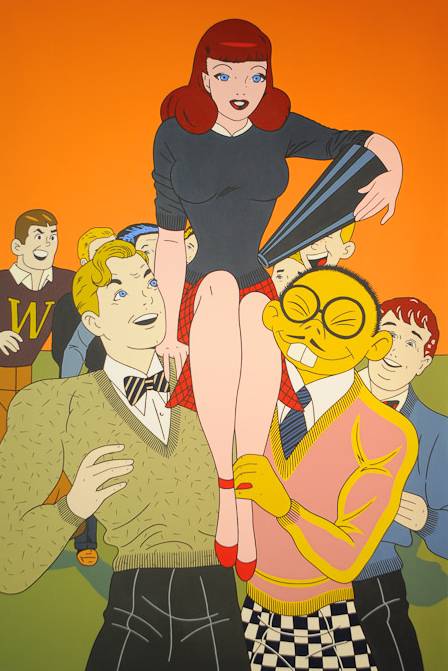

By projection: By an excess of self-regard: (USA! USA!)

By an excess of self-regard: (USA! USA!) By bad choices:

By bad choices:  By malign intent:

By malign intent:

Opening Oct. 2 at

Opening Oct. 2 at