The stately spiderwebs in the corners of Miss Havisham’s mansion are evidence of industry. Miss Havisham’s decay allowed fictional insects to work unhindered, their nets and clumps as intricate as any artifice of eternity.

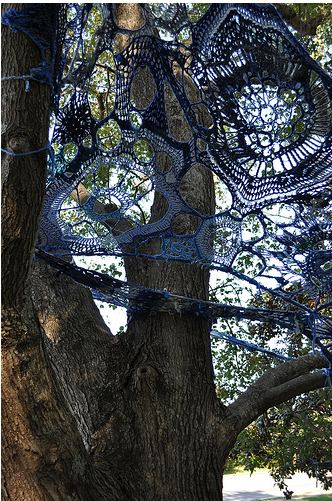

Mandy Greer crocheted the weedy banks of a urban river and floated them high in the trees. Filtered through forest light, her webbing became a kind of stained glass even as insects were eating it away.

From last summer’s performance, Mater Matrix Mother and Medium, Greer constructed her current exhibit of performance artifacts at Ohge Ltd. Gallery, obscurely titled Zuster Sweostor Systir, it’s a crocheted installation that overwhelms a dresser’s dummy and runs up a wall, along with photos, a documentary film, paper quilts and sculptures made of sewn leaves.

From last summer’s performance, Mater Matrix Mother and Medium, Greer constructed her current exhibit of performance artifacts at Ohge Ltd. Gallery, obscurely titled Zuster Sweostor Systir, it’s a crocheted installation that overwhelms a dresser’s dummy and runs up a wall, along with photos, a documentary film, paper quilts and sculptures made of sewn leaves.

It’s hard to collaborate with nature when nature has the home field advantage, out in the stage-set semi-wilds of a park, and even harder to assemble fragments from that engagement into an exhibit inside a small gallery.

Greer breezed through both challenges. Born too late to participate in the back-to-the-land communes that sprang up across Europe and the Americas in the late 1960s, Greer embodies the spirit of that time as an aesthetic but not just an aesthetic. She’s a mother-earth hippie, the sort of person who has become a sitcom figure of fun. The ideas her work espouses cue the laugh track in our heads, but her work shakes off cynical reactions like a dog bounding back with a stick shakes off the sea.

Greer breezed through both challenges. Born too late to participate in the back-to-the-land communes that sprang up across Europe and the Americas in the late 1960s, Greer embodies the spirit of that time as an aesthetic but not just an aesthetic. She’s a mother-earth hippie, the sort of person who has become a sitcom figure of fun. The ideas her work espouses cue the laugh track in our heads, but her work shakes off cynical reactions like a dog bounding back with a stick shakes off the sea.

Nature was not her only collaborator. She made the film that features performances of Zoe Scofield and Morgan Henderson with Ian Lucero; the photos with Jennifer Zwick (performance photos by Juniper Shuey), and sculptures with her husband Paul Margolis and her son Hazel.

Nature was not her only collaborator. She made the film that features performances of Zoe Scofield and Morgan Henderson with Ian Lucero; the photos with Jennifer Zwick (performance photos by Juniper Shuey), and sculptures with her husband Paul Margolis and her son Hazel.

Greer:

During my six weeks of residency at Camp Long in Seattle, spending long hours crocheting a fabricated river into the trees, I spent a great deal of time in quiet, face pressed to bark, watching ants travel, ducks tend to ducklings and watching small changes take place every day in my pond. A giant Barred Owl watched me, and it all felt very viscerally wild. But in between the quiet was the blast of horns from ships, a low hum of cars on the interstate and the weekly visit of the grounds keep with a leaf blower.

This forest, like most in Seattle — save for a few trees in Seward Park, has nothing to do with the deep mystery of the forest that was once here. It is fabricated, tended, groomed, minded, the old pond filled with a hose when it gets too low. An early photograph in the lodge shows the landscape barren, stripped of its organic past.

Zoe Scofield, on an early site visit, astutely observed how like a stage set it all was, and we intended to draw that out. The theatricality of the park is like that of a 18th-century folly, a ruin, at once referencing a romantic vision of nature as well as the human longing to experience something more sublime. I felt something of that sublime, following that great owl that watched me midday, I went off trail until I stood below it. And when its head glided around so that it could glare at me, warn me, I felt a jolt of instinct or electricity.

In the fabricated, tiny forests we tend, there is still buried the pull the human animal has always felt, to go back. As the summer came to ending, and I cut down the river, folded it up, I came back to my site over and over again as the forest turned to fall. With my son, I sifted for skeletal leaves on my hands and knees, just as we had sifted through dead leaves at the bottom of the pond looking for salamander egg sacks, finding the perfect lacy forms like Scandinavian lace discarded after a flood. I wanted to sew the forest together into a blanket, organize it all, to prepare for the winter, the leaves the same color as my hair, everything going red to brown.

We found nurse logs feeding Turkey Tail fungus like crocheted ruffles, and orange mushrooms under which we buried a mouse. On our hands and knees, it wasn’t urban recreation, but fairy tale. I collected my hair and Hazel’s hair, had it spun into yarn, and we each took on our roles in a landscape both out of our reach and right there with us, as organic as it is artificial.

Note: In the original draft, Miss Havisham was mistyped as Havishman.

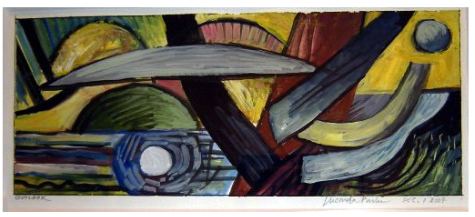

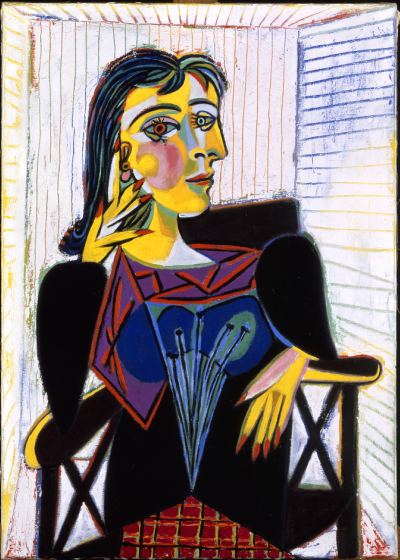

Weiner – The Crimes of Paris (Pink Hair Gel), 2008, oil on canvas, 64 x 197 inches

Weiner – The Crimes of Paris (Pink Hair Gel), 2008, oil on canvas, 64 x 197 inches

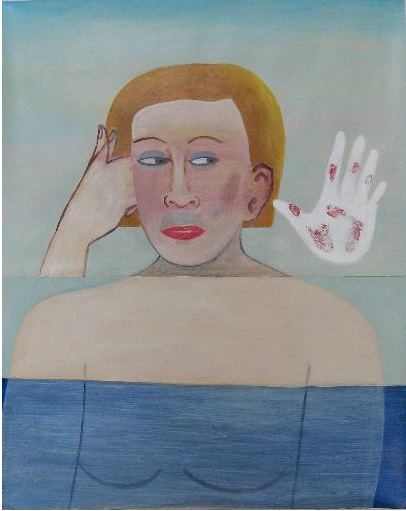

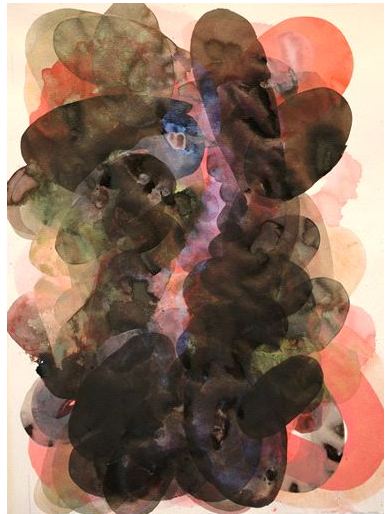

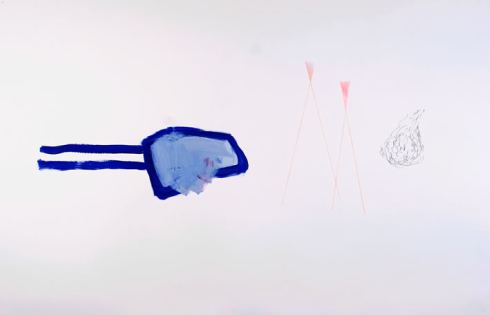

Fay Jones, Forget, Forgotten, acrylic/paper, 2009

Fay Jones, Forget, Forgotten, acrylic/paper, 2009 Gregory Grenon Me and My Ethereal Dress oil on plexiglas 2008

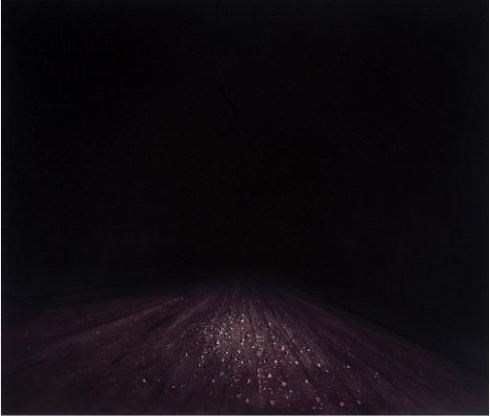

Gregory Grenon Me and My Ethereal Dress oil on plexiglas 2008 Michael Brophy, Silence 2, oil/canvas 2009

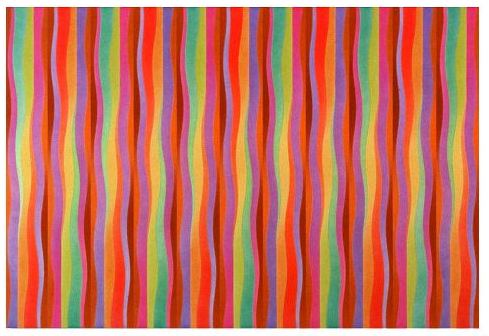

Michael Brophy, Silence 2, oil/canvas 2009 Francis Celentano Cirque Variation 11 acrylic on canvas 2006

Francis Celentano Cirque Variation 11 acrylic on canvas 2006  Jan Reaves Dutchman’s Britches mixed media on flax paper 2009

Jan Reaves Dutchman’s Britches mixed media on flax paper 2009

For more information, go

For more information, go

Its colors were

Its colors were

Fitch has a

Fitch has a MANTEL PIECE #2

MANTEL PIECE #2 For FM (nightshade),

For FM (nightshade), She is one of ten new

She is one of ten new