1. Eat only in your dreams. Bed and Board 2. Don’t bring your head to the table. (Or your hands.) Bad Manners, detail.

2. Don’t bring your head to the table. (Or your hands.) Bad Manners, detail.

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

1. Eat only in your dreams. Bed and Board 2. Don’t bring your head to the table. (Or your hands.) Bad Manners, detail.

2. Don’t bring your head to the table. (Or your hands.) Bad Manners, detail.

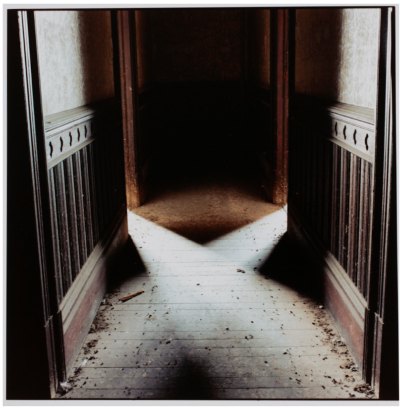

Spike Mafford takes photographs to erase himself. His claim is a romantic one, that wherever he is, he isn’t there. Because his subjects define themselves, they are not limited to theme or style. Mafford is nothing but the projectionist in a theater, running their movies. No one believes that a photograph has nothing to do with the photographer, any more than a painted ship upon a painted ocean owes nothing to the person standing in a studio holding the brush.

And yet, in shrinking his role, Mafford has managed to enlarge the remote purity of a remote world.

Paul Krassner once described a way to tell the difference between

news and dreaming. If you think what you’re reading is unlikely, flap

your arms. If you fly, you’re dreaming. Mafford’s prints fly.

Currently, he’s offering for sale 47 prints for $47 each, size variable. Details at the Spike Shop.

Examples:

They’d be accordions.

Drew Daly, COMPRESSION, 2006

One bureau, adhesive, lacquer

34 x 36 x 20.5 inches

Photo credit: Eric Eley

Peter Millett LEVERAGE, 2010

Peter Millett LEVERAGE, 2010

Welded steel

70 x 120 x 24 inches

Can measure his life.

John Kirchner My Sad Daily Life as Measured in

the Daily Paper, Newspaper, rain coat and steel

1994-2005

From muscle tissue with bacon scarf to smoke…

Derrick Jefferies

Anatomy (Muscle)

Polyethylene and tube lamps

2010

Backlight inkjet print & lightbox

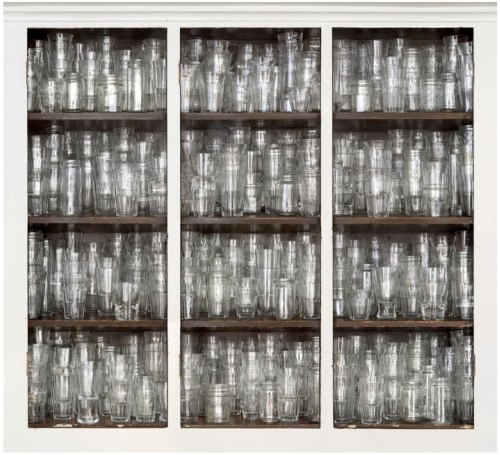

When I asked an addict what she got out of heroin, she said, “a shot of sainthood.” I thought of her when looking at Isaac Layman’s photographs at Lawrimore Project, the addict who has my face and sounds like I do on phone, sober now a long time and younger than I am but wrecked, always more wrecked.

Inside a drugged stupor, grace can deliver a hallucinated clarity. It’s only the world in Isaac Layman’s large prints, common as dirt, but his delivery has the force of revelation. Were you Saul, these photos would knock you off your horse.

Because everything he shoots is too real to be real, the exhibit’s title is, 110 Percent.

Because everything he shoots is too real to be real, the exhibit’s title is, 110 Percent.

From Flannery O’Conner’s A Good Man Is Hard To Find:

His voice seemed about to crack and the grandmother’s head cleared for an instant. She saw the man’s face twisted close to her own as if he were going to cry and she murmured, “Why you’re one of my babies. You’re one of my own children !” She reached out and touched him on the shoulder. The Misfit sprang back as if a snake had bitten him and shot her three times through the chest. Then he put his gun down on the ground and took off his glasses and began to clean them.

Hiram and Bobby Lee returned from the woods and stood over the ditch, looking down at the grandmother who half sat and half lay in a puddle of blood with her legs crossed under her like a child’s and her face smiling up at the cloudless sky.

Without his glasses, The Misfit’s eyes were red-rimmed and pale and defenseless-looking. “Take her off and thow her where you thown the others,” he said, picking up the cat that was rubbing itself against his leg.

“She was a talker, wasn’t she?” Bobby Lee said, sliding down the ditch with a yodel.

“She would of been a good woman,” The Misfit said, “if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.”

The moment that the grandmother is a good woman is the moment when the drug settles into the bloodstream and clears the mind, the moment when God speaks in the wilderness: the moment of transfixed understanding.

Working digitally, Layman combines layers of long exposures to get the same image stuck in a crater of a deepening visual repetition. It’s something like the idea of a rose is a rose, only simultaneously, as if everyone in a crowded room suddenly said “rose.” Everybody would say it a little differently.

Working digitally, Layman combines layers of long exposures to get the same image stuck in a crater of a deepening visual repetition. It’s something like the idea of a rose is a rose, only simultaneously, as if everyone in a crowded room suddenly said “rose.” Everybody would say it a little differently.

Below, Layman’s kitchen cabinet. He doesn’t own that many glasses.The photo is a long scan of the image, many exposures digitally stitched

together, like a quilt.

Max Beckmann said he didn’t need to abstract things, because “each object is unreal

Max Beckmann said he didn’t need to abstract things, because “each object is unreal

enough already.” Or, for Layman, too real.

More praise for Lawrimore Project: Curator Dan Cameron was in town for a lecture recently and took a day to look around with artists Gretchen Bennett and Joey Veltkamp.

Cameron’s Seattle report here. Below, what he had to say about LP:

Owned by Scott Lawrimore, a former Kucera protégé, the gallery is probably the most visually stunning commercial art space in the US, outstripping any comparable venue in either Chelsea or Culver City. The space is huge, and, more importantly, has been broken up by the Seattle firm Lead Pencil Studios into a cluster of rooms, each of which has an extremely precise character. Tall ceilings and indirect natural light are balanced by a renovation that leaves just enough of the original building’s quirks intact so that walking into Lawrimore feels like stepping into every artist’s ideal vision of an art gallery.

Lawrimore opened just in time for the recession. It’s still here, but this year is his financial best. He’s in the biz for the long haul, although his “visually stunning” venue is not. His lease is up next Halloween, his wife’s birthday. Anyone who bets on him signing another in that space will lose money. Layman closes on Aug. 14. Lawrimore has yet to schedule a show to follow it. If you want to see the place that beats the competition in Chelsea or Culver City, go now.

When in Tacoma, the last place on my list is the Museum of Glass. Its exhibits tend toward the didactic and its galleries have no natural light source, remarkable for a glass museum. With their low ceilings, they look like storage units.

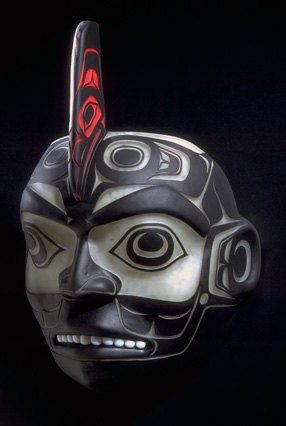

Even so, I intended to see Preston Singletary: Echoes, Fire, and Shadows long before now. (It closes Sept. 19.) It’s hard to admit I was hesitant to see what MOG would do with this artist, but there it is. Fortunately, I was wrong. Not once inside this mid-career survey did I think about the limitations of the galleries. Credit goes to curator Melissa G. Post and the museum’s design crew. The show looks terrific.

(All images reproduce sculpture by Singletary, taken from his website. Part of this post comes from a 2002 profile published in the PI. )

Singletary belongs to two tribes — the Tlingit nation into which he was born on his mother’s side, and glass, because glass at its core is tribal. In high school Singletary met lifelong friend Dante Marioni, whose father Paul took the boys to the counter-culture experiment in the woods that became Pilchuck Glass School. First generation artists in the studio glass movement were

Singletary belongs to two tribes — the Tlingit nation into which he was born on his mother’s side, and glass, because glass at its core is tribal. In high school Singletary met lifelong friend Dante Marioni, whose father Paul took the boys to the counter-culture experiment in the woods that became Pilchuck Glass School. First generation artists in the studio glass movement were

frequently at the house, and Singletary met them all.

After high school, glass offered an escape from college. Marioni managed to get his friend a job as night watchman at the Glass Eye. Thanks to his previous Pilchuck experience, he quickly moved onto the floor, blowing Christmas ornaments and other less seasonal decorations.

Glass was beginning to take off, and Singletary found himself along for

the ride.

What he liked best was the company. No other form of contemporary art is such a clan venture. With music

What he liked best was the company. No other form of contemporary art is such a clan venture. With music

blaring and heat pouring out of the furnaces, glass artists root for

each other, criticize, applaud and collaborate.

In 1984, after two years of glass factory work, Singletary became Ben Moore‘s gaffer. Moore’s studio offered not only a paycheck but the chance to blow with some of the best glass artists in

the world.

At Pilchuck, Singletary met Tony Jojola, who encouraged him to find a

At Pilchuck, Singletary met Tony Jojola, who encouraged him to find a

way to express his tribal heritage in the context of

contemporary glass.

In Alaska, he met David Svenson, a non-Native artist who opened up elements of Tlingit style Singletary hadn’t previously considered. Back in Seattle, Singletary thought the

hot glass bubble hanging precariously in front of him looked like a

Tlingit rain hat woven in cedar bark.

Eventually, he turned that shape upside down, transforming it into a

vase that all by itself would strike a familiar chord in Tlingit

circles.

Using a sandblasting and

Using a sandblasting and

stenciling technique he developed himself, he carved Tlingit designs on

the outer surface.

As Ramona Gault observed in a 1998 cover article in the magazine,

“Indian Artist,” the result is a “conical shape that opens upward like a

lily, its undersurface carved with an animal image that is split like a

Rorschach inkblot. When a light source is positioned above the vessel,

the carved image is cast in shadow on the surface where the vessel

sits.”

Beneath the stark, crisp clarity of his line, blunt old harmonies assert themselves. He

uses glass to express his Tlingit heritage, merging the ancient art of

glass blowing with even more ancient artistic practices of his people in

order to create a 21st-century version of tribal aesthetics.

He’s grateful for the Indian artists working in glass who came

He’s grateful for the Indian artists working in glass who came

before him, including Larry Ahvakana, Joe David, John Hagen, the late

Conrad House, Marvin Oliver and Susan A. Point, as well as his

contemporaries, such as Ed Archie Noisecat, who carved the masks

Singletary has used as molds.

Thirteen years before 1963, when Singletary was born, Robert Bruce Inverarity wrote that the art of the Northwest

Coast Native Americans was “flourishing when Captain Cook, on his last

voyage, reached the coast in 1778; it had passed its peak by 1910 and is

almost dead today.” Were he still alive, Inverarity would be happy to have been proved wrong. The glass end of the Northwest Coast tradition that began in Seattle has inspired Native artists around the world, and Singletary is among its leaders.

For those who need another reason to visit the Museum of Glass, Martin Blank‘s installation in the courtyard plays like frozen music.

There’s a one-word hint in Michiko Kakutani opening paragraph that her review of Laurence Gonzales’ novel will take a disparaging tone:

Think of a contemporary version of Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” in which an egotistical scientist’s creation is not a hideous-looking monster but a well-mannered teenage girl who quotes Shakespeare, listens to Tom Petty and uses Facebook and YouTube. This is the high-concept premise of Laurence Gonzales’s lumpy new novel, “Lucy.” (more)

Right. It’s “lumpy.” When lumpy is the first descriptive in a book review, that review will fall short of rave. The same can’t be said in visual art, where a critic might easily use the word as praise. In visual art, silky is not a top and lumpy a bottom. They are just another spectrum across which artists secure a place.

(Via)

Click here, via Molly Norris.

From a physical understanding of volume, Peter Millett built a cake.

His triangles join, like cupped hands, to make a bowl.

His triangles join, like cupped hands, to make a bowl.

FEAST BOWL, 2009

Painted wood

25 x 21 x 8 inches

$7,500

He moves back and forth between wood and steel, from carving into a solid to manipulating the empty skin of metal. In metal he can extend and twist a triangle. When triangles try to become a square, they fail, just as, in Millett’s mind, the American effort to remake Iraq in its image will fail.

He moves back and forth between wood and steel, from carving into a solid to manipulating the empty skin of metal. In metal he can extend and twist a triangle. When triangles try to become a square, they fail, just as, in Millett’s mind, the American effort to remake Iraq in its image will fail.

OPEN SQUARE, 2009

Welded steel

38 x 40 x 6 inches

He makes no models or drawings for his sculpture, preferring to work directly with what he calls the “real stuff.” While real stuff is in his hands, real stuff is in his head. His current exhibit at Greg Kucera Gallery, titled Skyscrapers, is a tribute to architects who blur the line between sculpture and buildings, making art that people inhabit high in the sky. With a tough elegance that compromises on nothing, his sculptures and

He makes no models or drawings for his sculpture, preferring to work directly with what he calls the “real stuff.” While real stuff is in his hands, real stuff is in his head. His current exhibit at Greg Kucera Gallery, titled Skyscrapers, is a tribute to architects who blur the line between sculpture and buildings, making art that people inhabit high in the sky. With a tough elegance that compromises on nothing, his sculptures and

drawings collaborate to create a weathered sense of place.

Lisa Corrin called his

work “disembodied architecture,” and that’s certainly part of it.

In HOTSEAT (2010

Welded steel

60 x 22 x 12 inches), his imaginary architecture becomes an emblem of mourning. The moire-pattern of its skin function as windows, something like the Bridge of Sighs but more what prisoners in their Guantánamo Bay holding cells might see through chain-link. The few accused with evidence of substantial crimes mingle with those who were in the wrong place at the wrong time and those who are guilty of thought crimes.

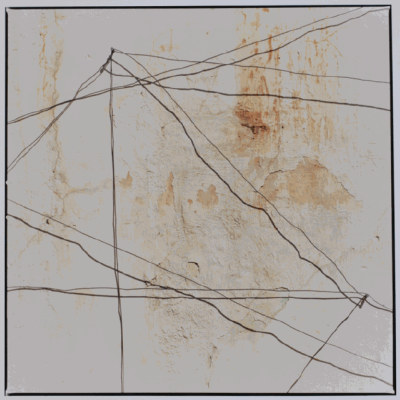

Decades ago, traveling in Iran, Millett was struck with the spare

Decades ago, traveling in Iran, Millett was struck with the spareThat admiration is the subtext of his modernist

form. Following Brancusi and Noguchi, his work is more elemental than

minimalist, rooted not just in nature but in human

nature. Millett has his rich color sense largely in check, giving free rein

only to rust. The range of his rust tonalities is a marvel, from cold

and dark to dappled across a fluid expanse and warm in places as

oven-baked bread.

Through August 14.

an ArtsJournal blog