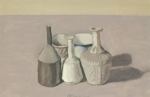

Giorgio Mordandi was not easily distracted. When fascism wreaked havoc in his

Giorgio Mordandi was not easily distracted. When fascism wreaked havoc in his

country and for decades after, he painted the same cluster of bottles, plates and tins in his studio. For

each small painting he found a rhythm, as if each were a universe that

could hum.

The artists in Target Practice: Painting Under Attack 1949-78

tend to be tone-deaf to that hum. They see what it leaves out, the

world brutally making and unmaking itself in a chaos of repression,

beauty, murder and freedom. Nor were they persuaded by the paint-driven

ambitions of the New York School, those who rode into history after

World War II as abstract expressionists. The giants of ApEx looked

inward and advanced the idea of timeless aesthetic values.

By 1949, time was up on timeless values. Curated by Michael Darling, Target Practice

at the Seattle Art Museum is a survey of the means, motives

and results of a global generation questioning the

lofty aspirations of painting as well as painting itself.

Scorched-earth

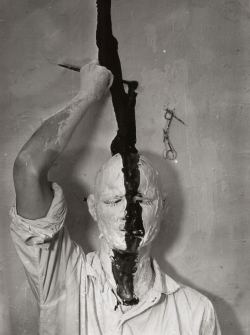

gardeners, they hoped to make way for a bloom. Darling picked not only

key work from key figures, he included a host of artists who are less familiar but hold up well in the context of the famous, such as Gunter Brus, using his body as canvas on the left, below.

Sharing space in the galleries, art from disparate sources clicks in place to generate the passion of a critical moment, dispensing with the usual thing –

Sharing space in the galleries, art from disparate sources clicks in place to generate the passion of a critical moment, dispensing with the usual thing –

scholarly dissection and imposition of hierarchy.

As a survey, it’s

wide but deep, and nobody in it comes up empty. The artists are as they

saw themselves, or, as Alan Ginsberg wrote about William Carlos

Williams, what “he tried to be among the bastards out there.”

Darling opens with Lucio Fontana‘s Concetto spaziale

from 1949. Fontana punched holes in the canvas as a means of marking

it. Aside from the novelty of his approach, his effect fits comfortably

inside the all-over realm familiar from ApEx. He tore into the canvas,

but nicely chewed what had already been chewed by others.

In the work of Shuzo Shimamoto, however, the innovative makes an appearance. In his Work (Holes)

from 1950, tears in whitewashed layers of newsprint approach their own

kind of tragic, and his scribbles in pencil on what is left of the

ground anticipate Cy Twombly.

Still, Shimamoto is firmly within ApEX, with new means to old results.

Back to Fontana, whose Concetto Spaziale from 1952 evokes Arthur Dove’s Fog Horns from 1929. Fontana’s single echoing circle stands in place of Dove’s three, but with the same reverberating lightness.

Who will look at Niki de Saint Phalle‘s ripe and juicy Tir neuf trous from 1964 (left) and not think of Joan Synder, who came later?

Who will look at Niki de Saint Phalle‘s ripe and juicy Tir neuf trous from 1964 (left) and not think of Joan Synder, who came later?

Unlike de Saint Phalle, Synder needs no guns in her studio. Her holes dripping paint are

made of paint, but both de Saint Phalle’s small canvas and Synder’s many

larger ones are not about their means of production. They are about female sexuality, and a ripeness that is past its peak.

Art comes from art, even when it doesn’t come from painting. Jasper Johns’ iconic Targets

from 1958 is rooted in early 20th-century ideas, especially Duchamp’s.

I’m rarely moved by Johns, the ice man of contemporary art, but in this

exhibit, the brilliant humor intrinsic to his endeavor is in high relief.

Fontano and to a lesser extent Alberto Burri made careers out of tearing up canvas, and Johns put the capstone on

Fontano and to a lesser extent Alberto Burri made careers out of tearing up canvas, and Johns put the capstone on

it and similar efforts in 1964, with a small pencil on paper

demonstration, Untitled (Cut, Tear, Scrap, Erase.) In vertical

columns, it does all those things, foreclosing on the option of doing

them again outside the repeat mode. How concise Johns is, and how

powerfully his work unfolds in the company of those who also tried to

make it new in the mid-20th century.

Sam Gilliam‘s Bow Form Construction, from his best period, the late 1960s and early 1970s, hangs near Lynda Benglis‘s Chi

from 1973. His painting-on-canvas sagging against the wall functions as a giant shawl, and hers as a tumorous type of

jewelry.

With his modesty, Richard Tuttle engaged the abject

with an elegance few equal, but who isn’t sick of Arman? Unlike Mordandi,

who traversed a tiny amount of ground without repeating himself,

Arman’s mounds of similar objects wear out their welcome quickly. Not the one in this show, which is a one-piece Arman rehabilitation

project: Ochre from 1967.

More than 200 tubes of paint

vomit their color, both tubes and paint squiggles trapped in clear

resin. Each squiggle is a gesture, and a gesture is, in Roland Barthes’

phrase (quoted in the catalog), “something like the surplus of an

action.”

The Japanese are a strong presence in this show,

especially Ushio Shinohara, whose performances (seen in large photos)

with paint are the equal of anything happening in Europe and America at

the time.

Shinohara:

Not content just to

use brushes, we came up with ways that would shock, aiming to evoke an

effect on those who would appreciate it.

Those who would appreciate it. He wasn’t trying to unnerve outsiders but to delight those who are capable of being delighted by him.

Johns’ Cut, Tear, Scape Erase is the cool end of Target Practice. Otto Muehl‘s Untitled

from 1963 (below, left) is one of the sensations on its hot end. Made of sand,

plaster, stockings and emulsion on sackcloth, with gaping holes bound by dark, ropey knots, its golds and blacks gleam like old jewels.

A word (or two) about the aesthetics of violence, celebrated in Target Practice. Walter Benjamin dealt with the subject in his much-celebrated 1936 essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, here.

A word (or two) about the aesthetics of violence, celebrated in Target Practice. Walter Benjamin dealt with the subject in his much-celebrated 1936 essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, here.

Benjamin wasn’t impressed by the manifestos of the Italian Futurists,

fascist to their cores. He must have thought that quoting from Futurist fascist poet Marinetti was sufficient to discredit him.

Apparently

not, but in light of this exhibit, Marinetti’s point of view is the

elephant in the gallery. Isn’t it more interesting to acknowledge it as

a kind of disgraced roots music? I like a machine-gunned canvas as much as the

next person, but what was the back story from the artists’ point of view?

Marinetti:

War

is beautiful because it enriches a flowery meadow with the fiery

orchids of machine guns…War is beautiful because it combines the

gunfire, the cannonades, the cease fire, the scents and the stench of

putrefaction into a symphony.

More on this exhibit to follow. It’s the single best survey of contemporary art ever mounted by the Seattle Art Museum.