A quick way to kill interest in a contemporary painting is to call it Abstract Expressionist, even neo-AbEx or in the tradition. As a tradition, it played itself out more than half a century ago. From dominant it fell to irretrievably historical, rooted in post-World War II New York with variants in other places (Paris, San Francisco, Seattle), all of which are also signed, sealed and delivered into the past.

Before AbEx, abstraction was reductive. ApbEx gave flesh to those bones. Exuberant, intuitive and of-the-moment, it allowed the hand and arm to speak for mind and represent matter. Pop pushed the movement aside by making the passions of the second generation look hysterical, ego-driven and (worst of all) contrived. Pop was cool and fun-loving. AbEx was neither. Its pioneers held their own, but artists interested in carrying it forward risk being accused of playing “torch songs on dead batteries,” as David Thomson unfairly wrote about Chet Baker.

The dead-battery-torch-song theory has only one flaw: It isn’t true. AbEx’s powerful progeny are everywhere, doing their bit for overall fields and the pleasures of push/pull, but the ones who rise to prominence refer to their family tree at their peril.

Here are a few:

Susan Rothenberg (Image via)

Susan Rothenberg (Image via)

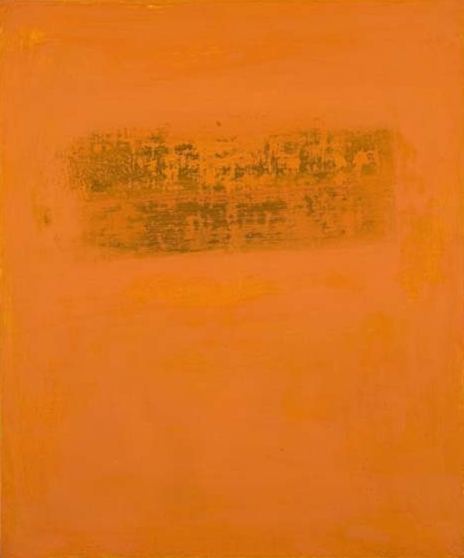

Mark Takamichi Miller (At Howard House)

Mark Takamichi Miller (At Howard House)

He’s replying to two items in this post: