Brodsky, from a 1996 essay in the New York Review of Books:

Prison is essentially a shortage of space made up for by a surplus of time.

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

Yuki Nakamura is interested in old, hand-blown electric lights. So is Chris Burden, Sheila Klein, Jim Hodges and Jeff Wall, among others. Because there is no more than a genetic hair’s difference between us and chimps, Terry Pratchett thinks electric lights are more interesting than stars. We swung down from the trees to cast our light against the dark.

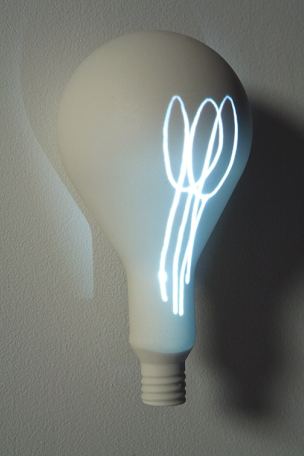

Nakamura, Filament Drawing, porcelain, DVD projection, 2010. The dark bulb is stage set for the electronic drawing, a line that advances, coils and disappears to reemerge for another try – let there be thin, fragile lines of experimental effort.

Light Bubbles (porcelain, plexiglas) depends upon conditions in the room, either projecting rabbit ear shadows or pooling its darks at each bulb’s base. Her plexiglas bases evoke Robert Irwin‘s, but with more of a back story. Her bulbs are containers for the thing contained, our history from torch to gas to common glow.

Light Bubbles (porcelain, plexiglas) depends upon conditions in the room, either projecting rabbit ear shadows or pooling its darks at each bulb’s base. Her plexiglas bases evoke Robert Irwin‘s, but with more of a back story. Her bulbs are containers for the thing contained, our history from torch to gas to common glow.

Nakamura is a kind of landscape artist, interested more in emblems than places, in maps that explore the meaning of the destination.

Nakamura is a kind of landscape artist, interested more in emblems than places, in maps that explore the meaning of the destination.

At Howard House through Jan. 30.

From Best of:

(Cuban born painter) Juan Alonso

wants to help out in Haiti but like a lot of us, he isn’t in a position

to donate a big wad of cash. Instead, he’s donated a beautiful piece of

his art called Sent. You have until Friday at noon to bid on it. Currently, the high bid is $550. All money raised goes to MercyCorps. More information here.

Sent, 2005, color pencil on paper. 19″ x 14″ image / 33 ½” x 28 ½” framed

I want to give beauty its due, but I’m a sucker for the beast.

The beauty:

Dale Chihuly, glass ceiling, Victoria And Albert Museum

The beasts:

The beasts:

Auroa Robson, from discarded plastic bottles, via

Judy Pfaff, made from whatever’s at hand.

Judy Pfaff, made from whatever’s at hand.

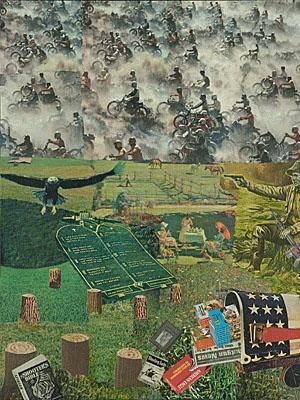

If a writer inserts a couple of paragraphs written by someone else into an essay without attribution, the end result is not called a collage. If an artist does the equivalent, it is. Art is an omnivore. It will eat anything. The law calls the practice fair use, although the protection the term implies exists only on a case-by-case basis. Since the 1980s, the art world has called it appropriation. The practice predates the movement by a century: It’s hard to imagine Modernism without it.

Even so, Bill Eppridge‘s outrage is understandable. (Via C-Monster)

Eppridge, Barstow to Vegas Motorcycle Race, 1971

Seattle’s Deborah Faye Lawrence, The Mysterious Allure of Rural America, 2008

Seattle’s Deborah Faye Lawrence, The Mysterious Allure of Rural America, 2008

Undeniable, from Eppridge:

Undeniable, from Eppridge:

The artist used my work to make her collaged work look better.

Debatable:

I risked my life many times to make photographs — in this case I was

standing on the skid outside a helicopter at 500 feet. Seeing my work

stolen in this manner just flat-out offends me because the artist used

something that she didn’t earn or create for her own benefit.

That’s cowboy logic. It’s true that you can’t rope a steer from your desk, but you can make powerful art without breaking a sweat.

Back to undeniable: Great image, Mr. Eppridge.

Life is cheap on TV. Cattlemen, town mayors, grocers and gunslingers are always going down in Western reruns. They slide to the floor in a bar or hit the dirt on Main Street, arms blow wide like Christ crucified or clutching their chests like Fred G. Sanford setting-up his guilt-trip line, “I’m coming to join you, Elizabeth.”

Whoever is left standing is the dream man, the American version of Mao. We celebrate not him but his parade-float iconography. No matter that cowboys worked long hours in menial jobs, like miners only in the open air and on horses. They’re remembered as rugged individualists, not trigger-happy alcoholics.

Justin Colt Beckman is always willing to play once upon a time as long as he can mess with what follows the intro. In his photos and video at Punch Gallery, he impersonates the familiar in order to undermine its credibility. Although his square-jawed good looks tip us that he’s the hero, when he goes for his gun, he does what TV cowboys never did – bungle the draw.

Sometimes he’s fairly subtle. Striking a Roy Rogers/Dale Evans pose, he and his wife are so close to the real thing (the real TV thing) that memory collides with doubt. Who are these people? Don’t we know them?

Beckman makes the commonplace rare. A bullet-ridden can? He painted it silver and serves it under glass.

Beckman makes the commonplace rare. A bullet-ridden can? He painted it silver and serves it under glass.

He’s the man firing over his shoulder, the light on his white hat. But because he shot his face in shadow (like a bad guy) and the flesh of his hand flattened, as if it’s pressed against the glass of the TV screen (screaming fake), he revels in his scam. In the heart of the he-man ideal, the hero cuts himself off from the past and charges blindly into the future, where he will, if the camera followed him, fade from view. Beckman’s version doesn’t ring entirely true, and that’s what’s good about it.

He’s the man firing over his shoulder, the light on his white hat. But because he shot his face in shadow (like a bad guy) and the flesh of his hand flattened, as if it’s pressed against the glass of the TV screen (screaming fake), he revels in his scam. In the heart of the he-man ideal, the hero cuts himself off from the past and charges blindly into the future, where he will, if the camera followed him, fade from view. Beckman’s version doesn’t ring entirely true, and that’s what’s good about it.

Through Jan. 30.

Through Jan. 30.

Hardgrave – tombs and worms and tumbling to decay: Death Sheild, with ribbon. Hardgrave is showing at the Joshua Liner Gallery through Feb. 6.

Eva Speer – flowers that rot on your wrist. An accessory for the prom in hell.

Eva Speer – flowers that rot on your wrist. An accessory for the prom in hell.

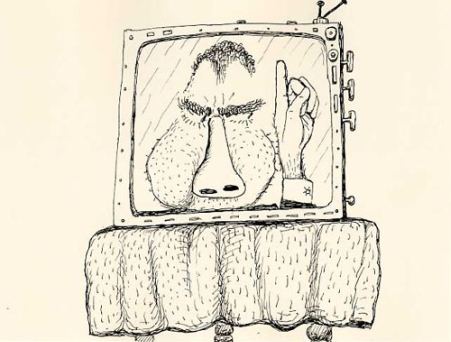

The dark prince of American history was smarter than any Republican to hold office after him, and not nearly as far-right on social issues as his party today. For personal resentment distilled to poison, however, he has no American rival.

From his papers, a new portion of which was released Monday: (Story via)

In a Jan. 26, 1970, memo to Haldeman and secretary Rose Mary Woods, the president demanded that the administration ”turn away from the policy of forcing our embassies abroad or those who receive assistance from the United States at home to move in the direction of off-beat art, music and literature.”

He called the Lincoln Center in New York a ”horrible monstrosity” that shows ”how decadent the modern art and architecture have become,” and declared modern art in embassies ”incredibly atrocious.”

”This is what the Kennedy-Shriver crowd believed in and they had every right to encourage this kind of stuff when they were in,” he wrote. ”But I have no intention whatever of continuing to encourage it now. If this forces a show-down and even some resignations it’s all right with me.”More than Nixon’s artistic sensibilities were at play here. He made the political calculation that ”those who are on the modern art and music kick are 95 percent against us anyway.”

If Macbeth and his wife were one person, Nixon would be him. Reagan was an empty suit, and Bush is too stupid for tragedy. He caused tragedies but could not embody them. The last Republican who was worthy of his part in the play is long dead, but his papers will continue to tantalize.

Philip Guston, via

an ArtsJournal blog