As long as artists are using your work, you’re not dead.

Leo Kenney, Formation No. 4, New Center, 1966 (At Seattle artREsource)

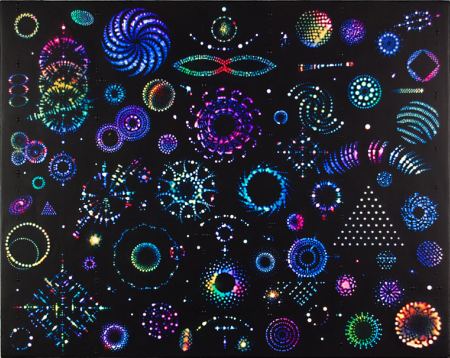

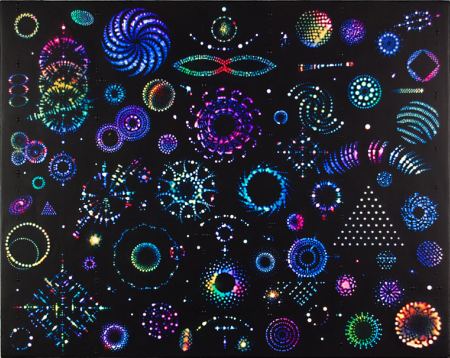

Jeffrey Simmons, Proxima, 2008 (At Greg Kucera)

Jeffrey Simmons, Proxima, 2008 (At Greg Kucera)

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

As long as artists are using your work, you’re not dead.

Leo Kenney, Formation No. 4, New Center, 1966 (At Seattle artREsource)

Jeffrey Simmons, Proxima, 2008 (At Greg Kucera)

Jeffrey Simmons, Proxima, 2008 (At Greg Kucera)

Susan Dory‘s paintings could not have existed before satellite transmissions, personal computers and cell phones. Like Tim Bavington‘s, her color sense is electronic. But while his stripes relate loosely to musical tones, her horizontal pulses appear to be celestial. When sending messages to galaxies far, far away, we could code them on her color wheel. There are worse ways of saying hello.

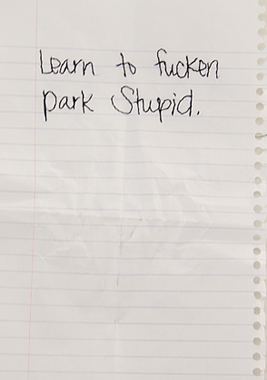

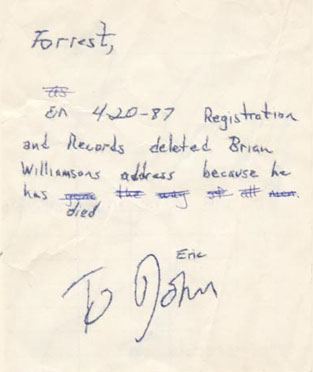

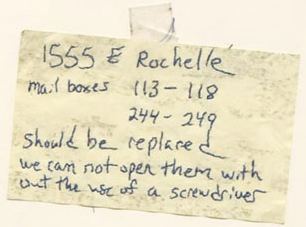

Post-It Notes are raw material for Marc Dombrosky, and so are notes on the backs of envelopes, receipts and letters. He cares about what people want to remember after they’ve forgotten it. Dombrosky is the kind of person who does not look up. What interests him is on the ground. When a written fragment speaks to him, he takes it home and reinforces the text by sewing over the script.

With homespun domestic skill, he returns trash to the bosom of the family. Lost or tossed messages are upgraded into a kind of street poetry.

Lately, Dombrosky has moved beyond saving the written word to saving thrown-away tarps and corny t-shirts. Beside eroded gold lettering, King of Pop, is a hand-embroidered black mass: The King of Pop develops a goiter.

Lately, Dombrosky has moved beyond saving the written word to saving thrown-away tarps and corny t-shirts. Beside eroded gold lettering, King of Pop, is a hand-embroidered black mass: The King of Pop develops a goiter.

Dombrosky’s Neverland at Platform Gallery through Feb. 20.

Dombrosky’s Neverland at Platform Gallery through Feb. 20.

In college in the late 1960s, a friend of a friend knew a guy named Fred. Thanks to Fred’s bad luck, his fame spread beyond his immediate circle. He walked into an elevator that wasn’t there and had to be rescued, clinging to the cables. If he was on a bus, it broke down. A teaching assistant lost his research paper. There were no copies. He went fishing, and his girlfriend’s hook snagged his cheek.

Rumor had it that Fred carried Kenneth Fearing’s Dirge in his pocket.

1-2-3 was the number he played but today the number came 3-2-1;bought his Carbide at 30 and it went to 29; had the favorite at Bowie but the track was slow–

One day, Fred’s fortunes rose. He had scored a summer job as life guard at a posh LA hotel. The pay was great, the work light and the atmosphere relaxing. What could go wrong? On the first day, arriving as dawn broke, he found a corpse floating face down in the water. Because he failed to jump in to check for vital signs, he never got a chance to sit in the life guard station.

Looking at Amir Zaki‘s digitally manipulated and color-saturated photos of life guard towers in L.A., Fred came to mind.

Not only is no one there, no one could be there.

Not only is no one there, no one could be there.

They are cool-school emblems of futility, a perfect match for Raymond Chandler’s view of swimming pools, a world away from David Hockney’s:

They are cool-school emblems of futility, a perfect match for Raymond Chandler’s view of swimming pools, a world away from David Hockney’s:

Nothing is emptier than an empty swimming pool.

At James Harris Gallery through Feb. 20

Calvin Coolidge

The business of America is business.

Andy Warhol

Making money is art and working is art and good

business is the best art.

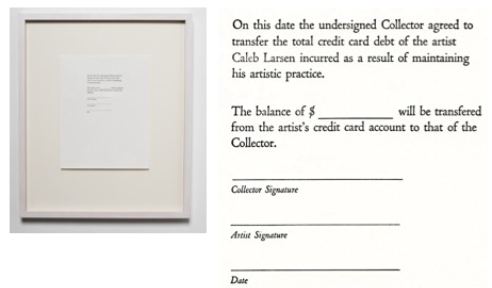

Caleb Larsen

Pay my (art-related) credit card debt.

All art has its own niche. Larsen has staked his in a narrow band of comic process.

A Tool To Deceive And Slaughter

is a black box that will always be attempting to auction itself off on

eBay. The collector who acquires it has to agree to relinquish it if

another offers a bid higher than the owner’s purchase price, and so on,

forever. It’s an answer of sorts to Robert Morris’s Box With the Sound of Its Own Making from 1961, owned by the Seattle Art Museum. Larsen’s is a box with the sound of its own selling.

The Entire Contents Of The Pen

The Entire Contents Of The Pen

(1,604 Linear Foot Drawing). Starting with a fresh fountain pen, Larsen

drew on an 9 x 12 inch piece of paper until the pen ran dry.

The drawing now contains everything that the pen once was.

Looks a bit like a Clyfford Still, updated by means of an obsessive-compulsive back story and, of course, the pen.

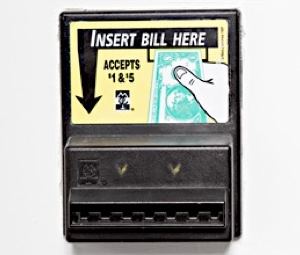

My favorite

My favorite scam

sculpture in the show is titled, $10,000 Sculpture (In Progress). It

accepts your money, and gives you nothing back. I slipped it three

dollar bills before coming to my senses. When there is so much in life

that disappoints in spite of our best efforts, it is positively

exhilarating to volunteer to be scammed, eyes wide open.

At Lawrimore Project through Feb. 13.

At Lawrimore Project through Feb. 13.

Tire Truck Buddha by NameTheRabbit via deviantART (Thanks, Paul O’Neil)

Gary Snyder, from Mother Earth: Her Whales

Gary Snyder, from Mother Earth: Her Whales

And Japan quibbles for words on

what kind of whales they can kill?

A once-great Buddhist nation

dribbles methyl mercury

like gonorrhea

in the sea.

…

Ah China, where are the tigers, the wild boars,

the monkeys,

like the snows of yesteryear

Gone in a mist, a flash, and the dry hard ground

Is parking space for fifty thousand trucks.

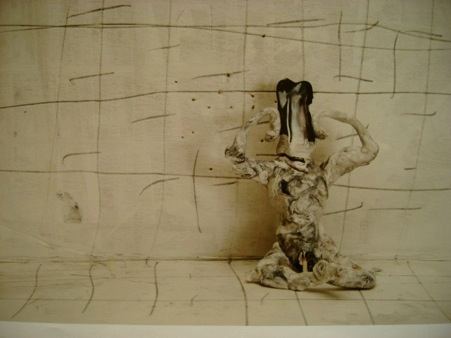

On a battered trunk sits a TV set so old and ugly it would get tossed from a donations box. When it’s plugged in, the screen lights to bluish-white and black static. Through its haze appears a head-and-shoulders shot of University of Washington art professor Doug Jeck, the terror of undergraduates. His big fake nose makes him look like a forlorn, featherless parrot. Covered in ceramic dust, he sings I Will Always Love You in a trembling falsetto.

My brother once owned a dog who could sing like a saxophone. Trying to encourage a performance, I half-crooned a howl to get him in the mood. Nothing. “You have to put your heart in it,” my brother said.

My brother once owned a dog who could sing like a saxophone. Trying to encourage a performance, I half-crooned a howl to get him in the mood. Nothing. “You have to put your heart in it,” my brother said.

Jeck puts his heart in it. Even if he’d never made anything else, for this one piece (Pathetique, 2003) he’d deserve a place in art’s memory bank.

But that’s not all. Jeck’s After Muybridge 2007 – suite of 9 photos of clay figures morphing from one frame to another – hangs on a wall.

Muybridge documented motion and Jeck breakdown. There’s a foolish attempt to rise again in the final frame, a burnt offering. Jeck’s figures lack the resilience of Thomas Schutte‘s lumpen freaks from, for instance, United Enemies. Instead, the Seattle artist parodies American individualism. His tiny people are masters of their own ships and captains of their own souls with nowhere to go and no way to get there.

Muybridge documented motion and Jeck breakdown. There’s a foolish attempt to rise again in the final frame, a burnt offering. Jeck’s figures lack the resilience of Thomas Schutte‘s lumpen freaks from, for instance, United Enemies. Instead, the Seattle artist parodies American individualism. His tiny people are masters of their own ships and captains of their own souls with nowhere to go and no way to get there.

Jeck is part of Wet and Leatherhard at Lawrimore Project, curated by Susie J. Lee. Instead of final products, Lee looks at process, at what a devotion to the muck of the earth does to contemporary artists.

Photos and a video document a 1972 performance by Jim Melchert and his friends. They stuck their heads in buckets of wet clay and waited for it to dry. Kristen Morgin recreates old tin toys with unfired replicas, the new far more fragile than the old. Wynne Greenwood‘s attempts at a vessel wouldn’t pass muster at summer camp, yet like the obese in bikinis, their bloated splendor insists on attention.

For Tim Roda, Meiro Koizumi and Ben Waterman, clay is a prop for performance. For Sterling Ruby, the ultimate performance cannot be controlled. It’s what happens in the firing. Artists make offerings, and the kiln decides who is Cain and who is Abel.

Through Feb. 13.

Through Feb. 13.

Unite and make something! The irrepressible David Shrigley‘s video for Pringle jumpers on Pacific Standard Time.

Spiders decorate their webs.

Guidelines for dealing with book (or gallery/museum) assistants, via Paul Constant.

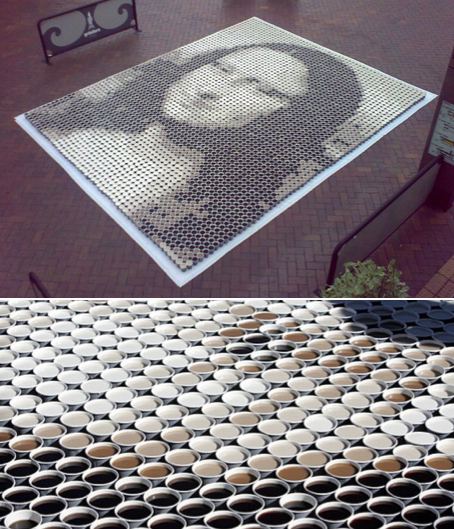

Art criticism for the stupid: From the London Times Online – Behind the smile Mona Lisa may have suffered from high cholesterol. It’s a painting, people. Plus, everybody knows Mona is made of coffee.

From Amy Goodwin

The nicest-possible-way-of-writing-a-negative-review award goes to Roberta Smith for her non-appreciation of Lynda Benglis’ recent efforts.

The nicest-possible-way-of-writing-a-negative-review award goes to Roberta Smith for her non-appreciation of Lynda Benglis’ recent efforts.

But all innovative, driven artists — of which Ms. Benglis is definitely one — have comfortable ruts they periodically fall into, or pitfalls they need to avoid. This show emphasizes hers, while giving notice that in all probability she will soon be working her way out of them.

Related: From NewsGrist – Ten most scathing reviews of last year. (Howard Halle, whoever that is, is dead wrong about Emily Jacir.)

The under-appreciated art blog award goes to John Perreault, whose Artopia is on ArtsJournal. Perreault’s last two entries, How the West Was Won: Fetish Finish and Fakes: Have Replicas Replaced Art? are among the best things I’ve read anywhere about anything in the new year. Perreault refuses to rush his posts. Once a week or less is all we get from him, but he makes every word count. His complexities are polished to a rare clarity.

Most-patronizing-post-from-an-art-blogger award goes to Tyler Green for his ruminations on Byron Kim. First Green says that Kim’s Synecdoche is not a great work of art. Green follows with the incredible opinion that the National Gallery of Art was right to acquire it anyway, in the interests of diversity.

Synecdoche, the Byron Kim installation acquired by the National Gallery of Art late last year, is

not a great work of art. It is closer to the end of every art

historical precedent it engages than it is to the beginning: abstract

painting, the use of the grid, monochrome painting,

abstraction-as-portraiture, minimalism, even its use of art world

insiders as models to help the work ‘get over,’ WWE-style….Still, it is a worthwhile acquisition for the National Gallery of Art,

a mostly federally-funded institution that should be collecting works

of art that engage the most prominent American philosophical

conversations. Synecdoche, which Kim began in 1991 and to which

he has added ever since, is one of the better examples of American

artists engaging with with the 1980s and 1990s debate about

multiculturalism in America.

I don’t agree about the piece, but if I did, I wouldn’t praise the National Gallery for buying it. Green seems to be supporting affirmative action for unqualified art works. Few things could be more insulting to artists of color.

More Green: I admire Green and read his blog daily. Learn a lot. Appreciate his hustle and intelligence. But his arch attacks on Jerry Saltz are getting old. As Green reports, linking to an ARTINFO blurb, Saltz used what Green calls “a four-letter epithet” in a facebook post. It’s fuck, by the way. Saltz typed the word fuck. Big fucking deal.

Stefano Catalani is now director of curatorial affairs/artistic director of the Bellevue Arts Museum, a promotion he earned. Working in an impossible building in a crafts niche, he has made his shows matter.

Michael Brophy’s paintings have good lungs. They expand to fill a sky with room left over for the land, which is frequently dark save for moonlight on water.

Michael Brophy’s paintings have good lungs. They expand to fill a sky with room left over for the land, which is frequently dark save for moonlight on water.

Charles D’Ambrosio described them best:

Most of Brophy’s landscapes are obviously wrecked, but there’s no nostalgia for the olden days, no melancholy, no sappy loss, largely because there’s also no initial shock. Ruin is painted as if it were eternal, as if there were nothing to recover, as if beauty persists, generous and spacious, even when the landscape of our longing does not.

The landscapes of our longing are back, both in moonlight and sunlight. For many painters, they never went away.

April Gornik paints big vistas as domestic interiors. Waterfalls on rocks look like cream pouring out of dark pitchers, and a stand of trees at night has a lacy edge. Alex Katz‘s twilight vistas look like billboards. Gayle Bard‘s rolling greens are immaculate, as if recently vacuumed. Elizabeth Sandvig‘s riotous abundance channels Fragonard. Joan Nelson‘s lost worlds could be carried in lockets. Robyn O’Neil‘s are medieval. Norman Lundin‘s muddy grounds are what you might see through the window of your car on a rainy day. Anselm Kiefer‘s wreckage marinates in the poisons of history.

Brophy’s landscapes wear their nerves on the outside of their bodies. A smear of his moonlight is like a dry cough. His trees have their ears pricked, waiting for the sound of an alien step. Remote but not austere, his landscapes reject the rare figures who attempt to move within them.

At G. Gibson Gallery through Feb. 20.

At G. Gibson Gallery through Feb. 20.

an ArtsJournal blog