The idea of high and low art is both discredited and thriving. Even those who say they don’t observe these boundaries do.

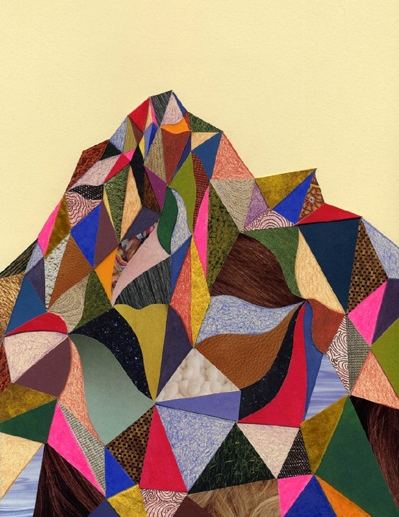

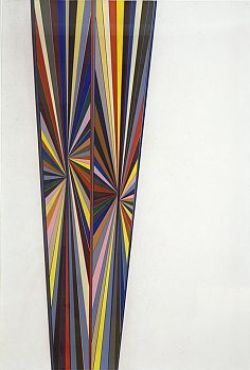

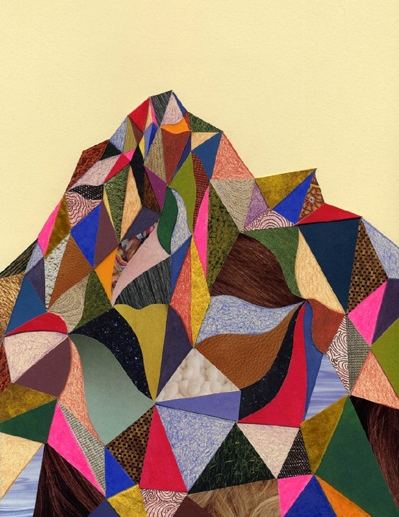

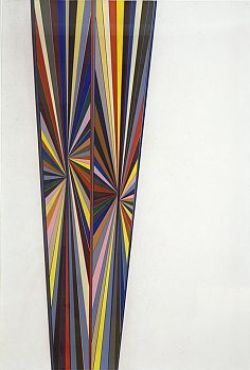

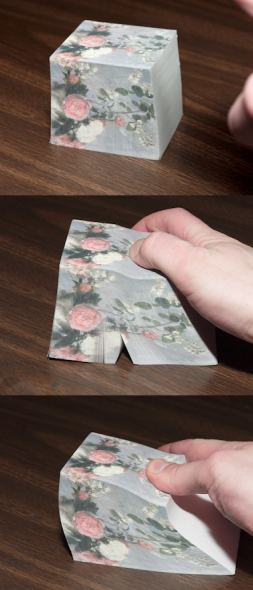

Art from Emily Pothast and Mark

Grotjahn. The jewelry from Spinthread on Etsy. (Via Shaun Kardinal)

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

The idea of high and low art is both discredited and thriving. Even those who say they don’t observe these boundaries do.

Art from Emily Pothast and Mark

Grotjahn. The jewelry from Spinthread on Etsy. (Via Shaun Kardinal)

In response to the question, “Do you want me to hold you?,” the toddler says, “Hold you,” raising his arms and looking beseechingly at his mother. In early childhood, time is elastic. What happens inside that time has not yet shaken off its primal glue. Pronouns clump together interchangeably.

Roger Shimomura spent his toddler years in Idaho at Camp Minikoda Minidoka, one of the detention camps that housed Japanese

Americans on the West Coast during World War II. Released when

he was 5 years old, he grew up watching his

parents try to rebuild their lives. What was stark for them was fluid for him, engendering a lifelong interest in the complexities of opposites that attract.

Currently at the Greg Kucera Gallery is an exhibit of small acrylic paintings titled, Minidoka on My Mind.

(Previous on this blog: Roger Shimomura, What racists see.)

(Previous on this blog: Roger Shimomura, What racists see.)

Having so recently written about Shimomura’s work, I want to defer to his analysis of it. He proves it any proof is needed that an artist statement can be a model of clarity, depth and humor.

I have often told my students that if making art is of paramount importance in their lives and that if they are willing to commit themselves to hard work and maintaining an engaged mind, they will eventually be able to free themselves o f everything they learned about art. I know from my experience that I have found this to be true.

After years of studious concern over content, I feel that I have either reached or sunk to a level of security where ideas for my work flow, unconscionably. It seems that at some point I no longer felt compelled to project my own point of view toward the things that concerned me. I found myself more interested in creating a visual forum that expressed ironic and contradictory attitudes towards these concerns.

This direction required many new resources and led me to practicing a form of self-legalized visual larceny. Using images from my past and immediate environments, from earlier and current work and using them as cultural metaphors, I became a dispassionate viewer of my own layering system.

My writings in performance art have provided me an opportunity to extend some of these ideas through a new medium. With the added features of time, sound and linear logic, interfaced with film, poetry and video, I discovered new possibilities in which to play with a lifetime’s accumulation of images. Suddenly I saw the relationship between the merchandise I used to covet and draw from old Sears catalogues and the bizarre collection of objects that now fill my house. So did I see the relationship between misleading reproductions from art history books and my mom’s old issues of Woman’s Day, between the music of the John Coltrane Quartet and the Salvation Army Band, between the stories that my grandmother left and the editorials in the local newspaper, between a meal of steamed black cod and the Colonel’s Wingdinger, between vintage Kurosawa and Johnny Socko, between Masterpiece Theatre and Pee-Wee’s Playhouse, between an Oreo cookie and a Chiquita Banana and between Minnie Mouse and one of Utamaro’s beauties.

A few weeks ago, Greg Kucera was poking around the ReStore and found Timothy Brown’s installation from the now defunct Crawl Space, titled Place/Setting. It appeared at the ReStore without attribution. (If anyone needed a dining set suspended in resin, that was their lucky day.) More recently, artist (and Kucera employee) Matt Browning was looking through a local Goodwill and found a framed photo by Chris Engman in pristine shape. The price? $5.

Engman is represented by Kucera, where the artist’s early photos, such as the found one, typically sell in the $1,200-$1,600 range. Turns out that Engman made only two prints of the image in question. One he gave to a friend, who still has it. The other he donated to Artist Trust.

What happened after that? Artist Trust is no more responsible for the art it sells than galleries are. In the case of Engman’s print, it got lucky. Its new owner is not just pleased to have found an Engman in his price range, he is not likely to mistreat the work of a peer.

This year’s Artist Trust auction takes place Saturday night. Choosing one artist out of the hundreds donating their work, I hope whoever buys Dawn Cerny’s We Get High (Not Very) (19″ x 24″,

Muslin, felt, silk) values it enough to take care of it. The prospect of it popping up at Goodwill in a banners’ box leaves me anything but high.

We repeat ourselves, and so do our products: endless iterations of us

and our desires, a baggy monster of consumables. Without crapping the

dice (prearranging the outcome, known in the sport as cheating), Sol

Hashemi approaches his wide-world of materials as if they were the elements of his own

crap game. Objects are in play by rules he invents on the spot, yet the

outcomes of his inquires, mounted in a gallery, reverberate beyond his

intentions.

They have juice. They are not, in the end, casual, no

matter how casually conceived. Currently at 4Culture Gallery is

Hashemi’s Object History Awareness, an assemblage of photos and

installations. Hashemi believes in the alchemical attraction between people, places and things. If he were answering a personals ad, he’d say yes to everybody. Any x standing next to any other y is instantly in a serious relationship.

Within his vast sea of connections, he allows for individual goals. Everyone wants to light fires in the studio, for instance, and almost everyone fails.

Hashemi feels for those failures. His grid of comic efforts at ignition

buries metaphor under the weight of the literal.

Studio fires

How about a birthday

How about a birthday

party? Each one marks progress towards the grave. Why not, since we’re

going there anyway, die faster? (Hope I die before I get old.)

Cake with Fast Lit Candles

Page through any book

Page through any book

on the history of art, and you’ll find flowers. Below, in an interaction with a note pad, are both the flowers

and the flipping through a text to find them.

Bouquet of Flowers (After Pissaro)

“Let a hundred flowers

“Let a hundred flowers

bloom,” said Chairman Mao. What followed was the flower-filled paradise of the Cultural Revolution. Even

though Hashemi is an artist instead of murderous thug and Communist Party Sun

God, his goals have a similarly lofty ring: Let a hundred forests

bloom. He’s starting with nine. Everyone has to start somewhere.

Potted Plants

Last year, at an exhibit honoring graduating B.F.A. students at the University of Washington, one of Hashemi’s sculptures disappeared during the opening party. Hashemi later found it beside a trash can, waiting for removal. Apparently, a volunteer doing a last bit of tidying up had mistaken it for rubble. How could that have happened? Below, a representative of Hashemi’s sculptural prowess:

Last year, at an exhibit honoring graduating B.F.A. students at the University of Washington, one of Hashemi’s sculptures disappeared during the opening party. Hashemi later found it beside a trash can, waiting for removal. Apparently, a volunteer doing a last bit of tidying up had mistaken it for rubble. How could that have happened? Below, a representative of Hashemi’s sculptural prowess:

I think it’s terrific. Through Feb. 26. (Previous on Hashemi and his frequent art partner, Jason Hirata, here. Michael Upchurch in the Seattle Times on the current exhibit here.)

I think it’s terrific. Through Feb. 26. (Previous on Hashemi and his frequent art partner, Jason Hirata, here. Michael Upchurch in the Seattle Times on the current exhibit here.)

In what sounds like a DIY version of a victory garden, artist Jennifer Towner just launched Seattle Art Barter, the place to go to trade screens for pastels, massages for frames – whatever one person has the other wants without shopping taxes and or a subtraction from anybody’s bank account. (About taxes: See Jack Daws’ comment.)

Considering that Ambach & Rice opened in 2003 as a hip toy store on Seattle’s Capitol Hill with a side serving of street and/or anime, its owners, Charlie and Amanda Kitchings, have come a long way, baby. Theirs is the only Northwest gallery accepted into NADA, and now it’s the only Northwest gallery that made the cut into New York’s Armory Art Fair, March 4-7.

It may also be the only Northwest gallery to apply to either fair. The recession is receding slowly in the Northwest. I profiled A&R a year ago January in the Seattle PI, back when there was a Seattle PI. Art fair admissions aside, A&R is an ambitious undertaking by anyone’s measure. Congratulations, Charlie and Amanda.

Richard Pryor:

Who you going to believe, me or your lying eyes?

Richard Pryor came to mind last night at the Greg Kucera Gallery, as per the following conversation:

Other person, talking to me:

Greg Kucera can sell anything, even a blue tarp.

Me:

It’s not a tarp. It’s a painting.

Other person:

Nonsense, Regina

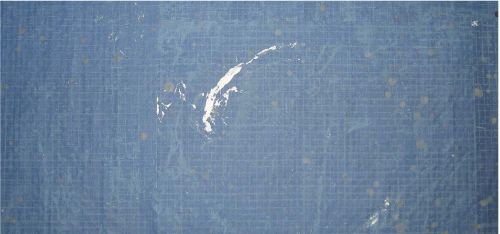

Whiting Tennis, BLUE TARP, 2007

Acrylic and paper collage on canvas

96 x 144 inches. Purchased by the Tacoma Art Museum.

Detail:

Detail:

It isn’t a painting on a tarp. It’s a painting of a tarp. This piece keeps fooling people who ordinarily know better, partly because Tennis isn’t thought of as an artist interested in trompe l’oeil. He’s drawn to what is battered by the world but makes versions of it in his studio instead of picking them up off the street.

It isn’t a painting on a tarp. It’s a painting of a tarp. This piece keeps fooling people who ordinarily know better, partly because Tennis isn’t thought of as an artist interested in trompe l’oeil. He’s drawn to what is battered by the world but makes versions of it in his studio instead of picking them up off the street.

To date, the only other painting in the Tennis’ lineup that falsely swears to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth is titled, Go Hawks, New Menus, from a diner. (2008

Acrylic, collage and pencil on canvas

36 x 48 inches)

An artist who makes a sculpture out of marzipan does not necessarily

want to see it on the menu. As Leonardo wrote in his notebook in 1470,

while serving Prince Ludovico Sforza of Milan:

I have observed with pain that my signor Ludovico and his court

gobble up all the sculptures I give them, right to the last morsel, and

now I am determined to find other means that do not taste as good, so

that my works may survive. (more)

Impersonating a cookie has risks. Janine

Antoni made art history out of satiated desire – her teeth marks

left in a 600- pound mound of chocolate. Thanks to her, addiction took sculptural form (Gnaw,

1992).

What follows is a small survey of artists who explore the

issue of food as the odious cost of staying alive.

Alex Schweder, Still-life of

Beefsteak and Cheese

Paper, Ink, & Scented Varnish, each sheet 34″ x 21.5″, 2004 (Lawrimore

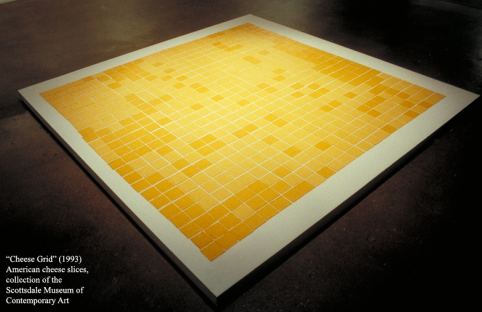

Project) Walk on this – The Art Guys (Cheese Grid,

Walk on this – The Art Guys (Cheese Grid,

1993)

Marc Horowitz

“brings his research of socially acceptable narcotics to more’s r&d

lab in efforts to help increase demand for and sweeten M.O.R.E.’s

services

.”

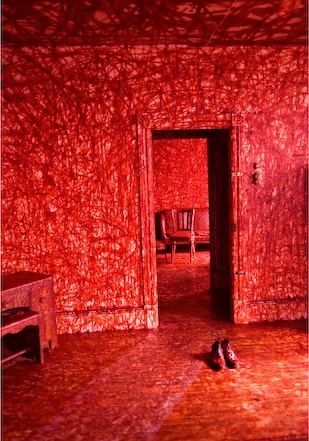

![]() Cosimo

Cosimo

Cavallaro – from his room coated with liquefied cheese, via Walter

Robinson

Here’s looking at you,

Here’s looking at you,

potato eyes: Ryan Horvath – P.M.S.

(detail)

MEDIA potatoes, glass, light

SIZE 18″ x 18″ x 80″

DATE 1997

DESCRIPTION potato mosaic structure, one month duration

Also from Horvath, the

Also from Horvath, the

cane you can’t count on, made of sugar. Cane 36″ x 5″ x 1″

2004

Blast from the past:

Blast from the past:

Alfred

Gescheidt

Untitled

1949

vintage gelatin silver print

Aesthetic grandson of Gescheidt: Eric Yahnker, Berry Astonished, 2009 Colored pencil on paper

Aesthetic grandson of Gescheidt: Eric Yahnker, Berry Astonished, 2009 Colored pencil on paper

Related post from this blog – The banana downfall, a visual survey

Related post from this blog – The banana downfall, a visual survey

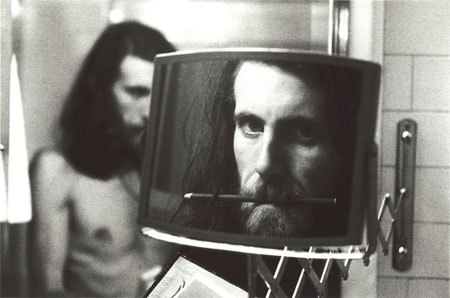

Best known as a member of Crosby, Stills and Nash (later, briefly, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young) Graham Nash is also a photographer and photography collector. In 1990 he co-founded (with R. Mac Holbert) Nash Editions, the first major fine-art digital printmaking studio.

Music and photography he likes to conflate.

When I look at Ansel Adams’s print Moonrise Over Hernandez I can feel the basses and cellos in the shadows – I can hear the violins in the clouds. (via)

Ansel Adams. Nash is not afraid to buck the trends. The stately perfection of Adams, his pristine view of an immaculate natural world, parallels the harmonies of CSN. Both Adams and CSN are out of date but not discredited. They hold their place, ready to shine when the time is again right for their lucid reassurances.

As a photographer, Nash favors a refined Surrealism that showcases his technical prowess – more Jerry Uelsmann than Ralph Eugene Meatyard.

Nash, Self-Portrait at the Plaza Hotel, New York, New York 1974 When he dispenses with the elaborate set up and just takes the shot, however, he can be convincing. His performance portraits are pure but not corny.

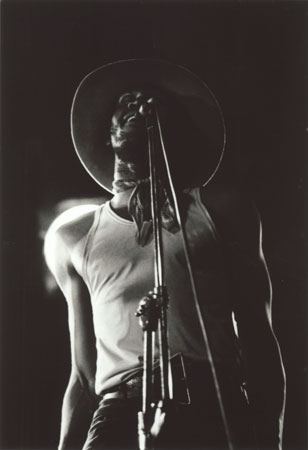

When he dispenses with the elaborate set up and just takes the shot, however, he can be convincing. His performance portraits are pure but not corny.

Nash, Taj Mahal at the Mariposa Folk Festival, Centre Island, Toronto, 1970

Nash also has the rare ability to look beyond his own practice, which is why he’s an excellent choice to curate a survey of rock ‘n’ roll photographs at the Experience Music Project in Seattle, titled, Taking Aim. There are 96 photos from 40 photographers. The vast majority are black and white, and the majority feature musicians from Nash’s era. (His view is wide but not unlimited.) All but a few were printed by Nash Editions, which means, they’re crisp.

Nash also has the rare ability to look beyond his own practice, which is why he’s an excellent choice to curate a survey of rock ‘n’ roll photographs at the Experience Music Project in Seattle, titled, Taking Aim. There are 96 photos from 40 photographers. The vast majority are black and white, and the majority feature musicians from Nash’s era. (His view is wide but not unlimited.) All but a few were printed by Nash Editions, which means, they’re crisp.

These photos track Nash’s story: where he started (looking up to Buddy Holly), his high points (when he knew everybody), and his appreciation of what came after (less of this). EMP says the show will travel. Great. Without knowing where, I can confidently predict it will look better there. As Frank Gehry carefully explained to the press at EMP’s opening, he designed the exterior only.

The inside is a techie-music-science fiction curio shop. Cluttered and cramped, it has one decent performance space but nothing that comes close to adequate for looking at art. Imagine an exhibit inside a Radio Shack with the batteries missing, and you’re there.

Other issues that might cause rancor: Not only are the 1960s overrepresented, so are white males, both in front of the camera and behind it.

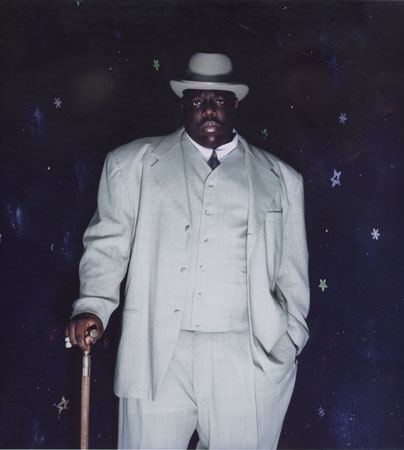

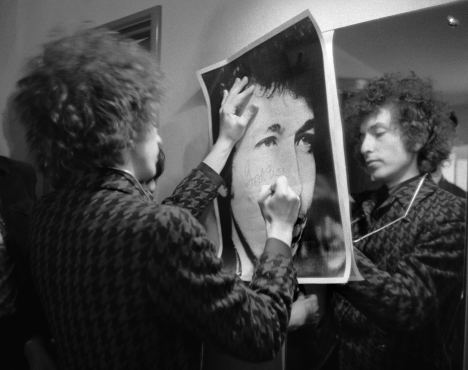

What this show has going for it is the veracity of its inclusions, from portraits to performance shots and casuals snapped when the artists were taking a break, letting off steam or presuming (wrongly) that they were alone. Some of the photographers rate in the art world (Nash, Annie Leibovitz, Richard Avedon, Charles Peterson, Alice Wheeler, Mick Rock and Dennis Hopper). Most are working stiffs, on the scene and elbows out. The shots they took are amazing.

What this show has going for it is the veracity of its inclusions, from portraits to performance shots and casuals snapped when the artists were taking a break, letting off steam or presuming (wrongly) that they were alone. Some of the photographers rate in the art world (Nash, Annie Leibovitz, Richard Avedon, Charles Peterson, Alice Wheeler, Mick Rock and Dennis Hopper). Most are working stiffs, on the scene and elbows out. The shots they took are amazing.

Barron Claiborne, Notorious B.I.G. New York, New York, 2003

Barry Feinstein, Bob Dylan, 1966 Paris (He’s signing “God Bless” as Feinstein turned him into his own personal trinity.)

Barry Feinstein, Bob Dylan, 1966 Paris (He’s signing “God Bless” as Feinstein turned him into his own personal trinity.)

Two from Seattle:

Two from Seattle:

Alice Wheeler, Neko Case and Her Boyfriends, Tacoma, Washington, 2000

Charles Peterson, Crowd with body surfers during Mudhoney’s set at the KNDD Endfest, Kitsap County, Washington, 1991

Charles Peterson, Crowd with body surfers during Mudhoney’s set at the KNDD Endfest, Kitsap County, Washington, 1991 At EMP through May 23. The catalog is worth having.

At EMP through May 23. The catalog is worth having.

an ArtsJournal blog