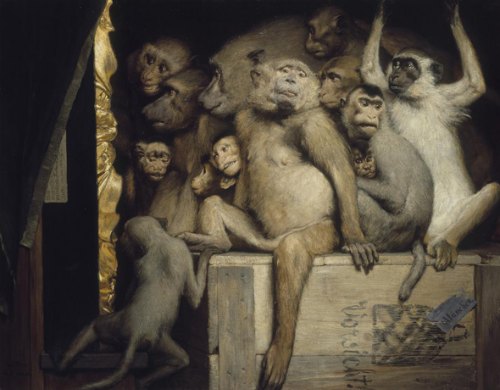

The Frye is Rip Van Winkle with a sequel. It slumbered through the 20th Century and woke up in the 21st. Here’s the sequel: After striving mightily to keep its eyes open, it’s once again nodding off.

Little that Charles and Emma Frye acquired rises to the ranks of first-rate. Charles Frye saw Modernism as an unworthy aberration. Ida Kaye Greathouse, who followed her husband Charles Walser as the museum’s head, was if anything more conservative, although I am fond of a core of her late 19th and early 20th-century American purchases. Yes, she was after big names at reduced prices, rather than the best possible examples of same, but even so she managed to snag some great pictures.

Senior curator Robin Held sees it as her job to present the collections in the best possible light. She even brought on staff a specialist in the so-called Munich Secession, to help her. Fine, I thought. Let Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker handle the mixed-bag legacy and allow Held to focus on the contemporary moment. That’s her strength and the reason the Seattle audience developed high expectations from a dubious little institution.

Instead, legacy is in the driver’s seat. Everything now on view dares to be dull.

First up, Ida Kay Greathhouse: A Tribute. Where are her American greats? Not on view.

John Singer Sargent must have been short of cash to paint the vacuous flattery known as Mrs. Frederick William Roller from 1895. Those to continue to see him as shallow can bolster their viewpoint at the Frye.

Thomas Moran did his best work at Yellowstone National Park. He’s a large part of the reason we have national parks. In Venice in 1908, however, he turned in a poor imitation of Turner.

Thomas Moran did his best work at Yellowstone National Park. He’s a large part of the reason we have national parks. In Venice in 1908, however, he turned in a poor imitation of Turner.

Greathouse adored the Russian expatriate Nicolai Ivanovich Fechin. I imagine she had her pick of that market. Below, Lady in Pink (Portrait of Natalia

Greathouse adored the Russian expatriate Nicolai Ivanovich Fechin. I imagine she had her pick of that market. Below, Lady in Pink (Portrait of Natalia

Podbelskaya), 1912.

Onward to another Greathouse tick: Northern Latitudes: The Frye and Alaska, featuring Jules Dahlager, Ted Lambert, Sydney Laurence, Fred

Onward to another Greathouse tick: Northern Latitudes: The Frye and Alaska, featuring Jules Dahlager, Ted Lambert, Sydney Laurence, Fred

Machetanz, Theodore Richardson, Cleveland Rockwell, Jonathan Van Zyle,

and Eustace Ziegler. They’re not all terrible painters. I like Rockwell, but why these painters? And why didn’t she pick better examples? Most of the ones she brought home are bombastic at best.

That leaves

Tête-à-tête: 150 paintings from the Charles and Emma’s overexposed, profoundly mediocre holdings; Fred Machetanz (1908-2002) photos lithographs of the standard sublime in Alaska, and the somewhat interesting A Day in Skaguay, filmed by Burton Holmes (1870-1958), who in 1904 coined the term travelogue to advertise travel lectures with projections of hand-painted glass-lantern slides and early films. Interesting that everyone was fashionable and white in Alaska during those early years.

Out of kindness I’m skipping the exhibit exclaiming over Charles Frye’s entrepreneurial efforts. (He was a meat packer and landlord.) Museums need to remember that’s it’s OK to take the money, but they don’t have to kiss the customer on the lips.

The Frye picks up the pace in the fall.

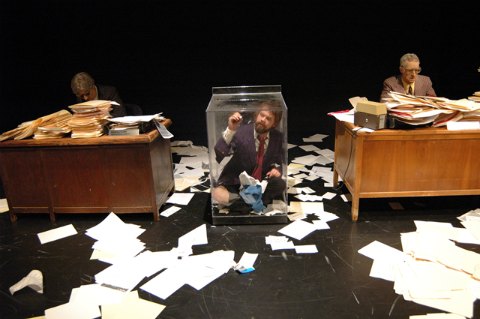

Opening Oct. 9, still more about the Munich Secession: Séance: Albert von Keller and the Occult, but there’s also Implied Violence: Yes and More and Yes and Yes and Why, featuring sculptures, costumes, props, masks, video- and photo-documentation of

selected past performances of the Seattle performance group as well as a new performance created for the Frye. That could be good. Who gets the catalog? Keller and his swooning ladies, of course.

For the finales, both sets of judges pulled themselves together and made a case that they deserve to be there.

For the finales, both sets of judges pulled themselves together and made a case that they deserve to be there.

More from those who are not afraid to go back in order to go forward.

More from those who are not afraid to go back in order to go forward.

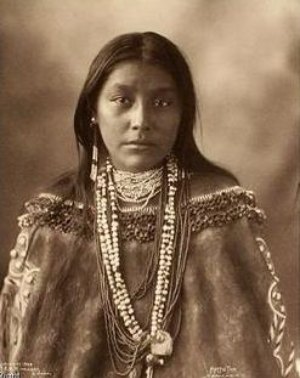

Working with Seattle Art Museum’s Barbara Brotherton, curator of Native American art, the tribe has decided to let its objects tell the tale.

Working with Seattle Art Museum’s Barbara Brotherton, curator of Native American art, the tribe has decided to let its objects tell the tale.

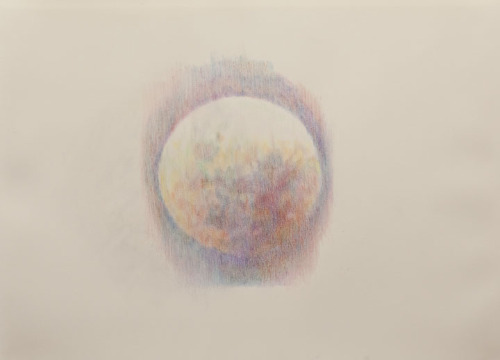

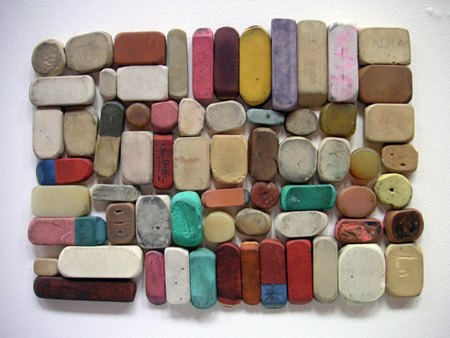

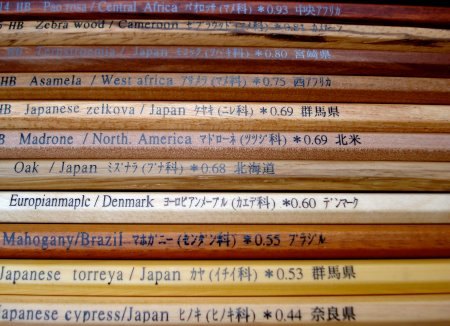

Colleen Wood, Pencils via

Colleen Wood, Pencils via

(For more of similar, see

(For more of similar, see