In response to the question, “Do you want me to hold you?,” the toddler says, “Hold you,” raising his arms and looking beseechingly at his mother. In early childhood, time is elastic. What happens inside that time has not yet shaken off its primal glue. Pronouns clump together interchangeably.

Roger Shimomura spent his toddler years in Idaho at Camp Minikoda Minidoka, one of the detention camps that housed Japanese

Americans on the West Coast during World War II. Released when

he was 5 years old, he grew up watching his

parents try to rebuild their lives. What was stark for them was fluid for him, engendering a lifelong interest in the complexities of opposites that attract.

Currently at the Greg Kucera Gallery is an exhibit of small acrylic paintings titled, Minidoka on My Mind.

(Previous on this blog: Roger Shimomura, What racists see.)

(Previous on this blog: Roger Shimomura, What racists see.)

Having so recently written about Shimomura’s work, I want to defer to his analysis of it. He proves it any proof is needed that an artist statement can be a model of clarity, depth and humor.

I have often told my students that if making art is of paramount importance in their lives and that if they are willing to commit themselves to hard work and maintaining an engaged mind, they will eventually be able to free themselves o f everything they learned about art. I know from my experience that I have found this to be true.

After years of studious concern over content, I feel that I have either reached or sunk to a level of security where ideas for my work flow, unconscionably. It seems that at some point I no longer felt compelled to project my own point of view toward the things that concerned me. I found myself more interested in creating a visual forum that expressed ironic and contradictory attitudes towards these concerns.

This direction required many new resources and led me to practicing a form of self-legalized visual larceny. Using images from my past and immediate environments, from earlier and current work and using them as cultural metaphors, I became a dispassionate viewer of my own layering system.

My writings in performance art have provided me an opportunity to extend some of these ideas through a new medium. With the added features of time, sound and linear logic, interfaced with film, poetry and video, I discovered new possibilities in which to play with a lifetime’s accumulation of images. Suddenly I saw the relationship between the merchandise I used to covet and draw from old Sears catalogues and the bizarre collection of objects that now fill my house. So did I see the relationship between misleading reproductions from art history books and my mom’s old issues of Woman’s Day, between the music of the John Coltrane Quartet and the Salvation Army Band, between the stories that my grandmother left and the editorials in the local newspaper, between a meal of steamed black cod and the Colonel’s Wingdinger, between vintage Kurosawa and Johnny Socko, between Masterpiece Theatre and Pee-Wee’s Playhouse, between an Oreo cookie and a Chiquita Banana and between Minnie Mouse and one of Utamaro’s beauties.

How about a birthday

How about a birthday Page through any book

Page through any book “Let a hundred flowers

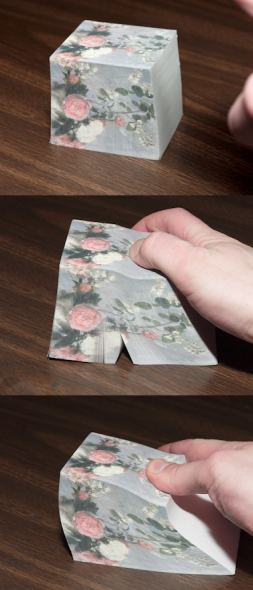

“Let a hundred flowers Last year, at an exhibit honoring graduating B.F.A. students at the University of Washington, one of Hashemi’s sculptures disappeared during the opening party. Hashemi later found it beside a trash can, waiting for removal. Apparently, a volunteer doing a last bit of tidying up had mistaken it for rubble. How could that have happened? Below, a representative of Hashemi’s sculptural prowess:

Last year, at an exhibit honoring graduating B.F.A. students at the University of Washington, one of Hashemi’s sculptures disappeared during the opening party. Hashemi later found it beside a trash can, waiting for removal. Apparently, a volunteer doing a last bit of tidying up had mistaken it for rubble. How could that have happened? Below, a representative of Hashemi’s sculptural prowess:  I think it’s terrific. Through Feb. 26. (Previous on Hashemi and his frequent art partner, Jason Hirata,

I think it’s terrific. Through Feb. 26. (Previous on Hashemi and his frequent art partner, Jason Hirata,  Detail:

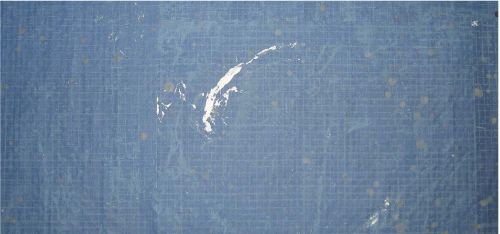

Detail: It isn’t a painting on a tarp. It’s a painting of a tarp. This piece keeps fooling people who ordinarily know better, partly because Tennis isn’t thought of as an artist interested in

It isn’t a painting on a tarp. It’s a painting of a tarp. This piece keeps fooling people who ordinarily know better, partly because Tennis isn’t thought of as an artist interested in

Walk on this –

Walk on this –

Here’s looking at you,

Here’s looking at you, Also from Horvath, the

Also from Horvath, the Blast from the past:

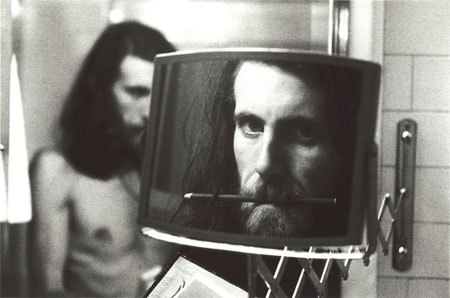

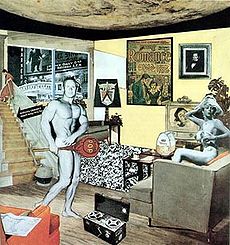

Blast from the past: Aesthetic grandson of Gescheidt:

Aesthetic grandson of Gescheidt:  Related post from this blog –

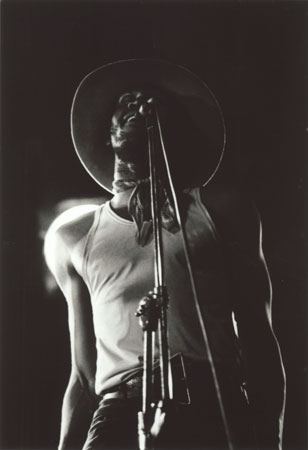

Related post from this blog –  When he dispenses with the elaborate set up and just takes the shot, however, he can be convincing. His performance portraits are pure but not corny.

When he dispenses with the elaborate set up and just takes the shot, however, he can be convincing. His performance portraits are pure but not corny. Nash also has the rare ability to look beyond his own practice, which is why he’s an excellent choice to curate a survey of rock ‘n’ roll photographs at the

Nash also has the rare ability to look beyond his own practice, which is why he’s an excellent choice to curate a survey of rock ‘n’ roll photographs at the

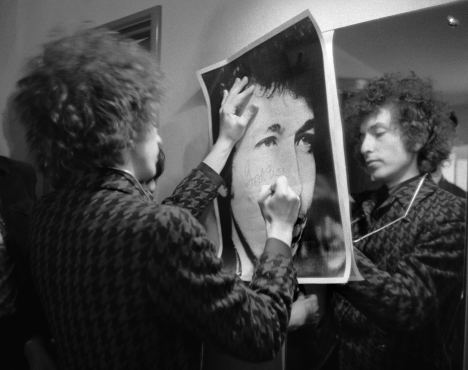

Barry Feinstein, Bob Dylan, 1966 Paris (He’s signing “God Bless” as Feinstein turned him into his own personal trinity.)

Barry Feinstein, Bob Dylan, 1966 Paris (He’s signing “God Bless” as Feinstein turned him into his own personal trinity.) Two from Seattle:

Two from Seattle: Charles Peterson, Crowd with body surfers during Mudhoney’s set at the KNDD Endfest, Kitsap County, Washington, 1991

Charles Peterson, Crowd with body surfers during Mudhoney’s set at the KNDD Endfest, Kitsap County, Washington, 1991 At EMP through May 23. The

At EMP through May 23. The  Related:

Related:  Our tact, of course. ANABA art blogger Martin Bromirski offered a choice example of blogger good manners in

Our tact, of course. ANABA art blogger Martin Bromirski offered a choice example of blogger good manners in The point of this post is the first quote from Gober, below. I could have posted it by itself, but I succumbed to the temptation to window dress.

The point of this post is the first quote from Gober, below. I could have posted it by itself, but I succumbed to the temptation to window dress.