Life is cheap on TV. Cattlemen, town mayors, grocers and gunslingers are always going down in Western reruns. They slide to the floor in a bar or hit the dirt on Main Street, arms blow wide like Christ crucified or clutching their chests like Fred G. Sanford setting-up his guilt-trip line, “I’m coming to join you, Elizabeth.”

Whoever is left standing is the dream man, the American version of Mao. We celebrate not him but his parade-float iconography. No matter that cowboys worked long hours in menial jobs, like miners only in the open air and on horses. They’re remembered as rugged individualists, not trigger-happy alcoholics.

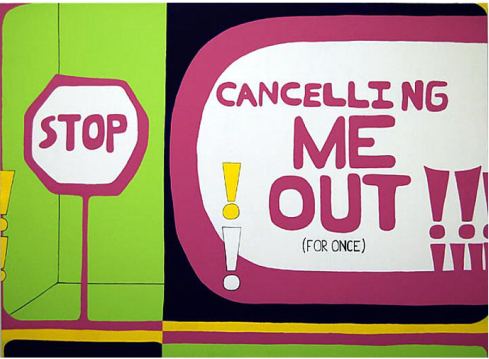

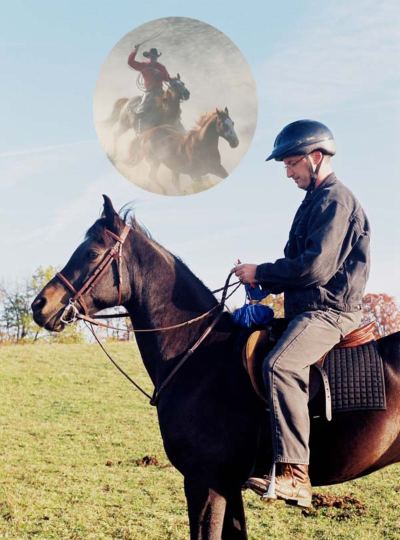

Justin Colt Beckman is always willing to play once upon a time as long as he can mess with what follows the intro. In his photos and video at Punch Gallery, he impersonates the familiar in order to undermine its credibility. Although his square-jawed good looks tip us that he’s the hero, when he goes for his gun, he does what TV cowboys never did – bungle the draw.

Sometimes he’s fairly subtle. Striking a Roy Rogers/Dale Evans pose, he and his wife are so close to the real thing (the real TV thing) that memory collides with doubt. Who are these people? Don’t we know them?

Beckman makes the commonplace rare. A bullet-ridden can? He painted it silver and serves it under glass.

Beckman makes the commonplace rare. A bullet-ridden can? He painted it silver and serves it under glass.

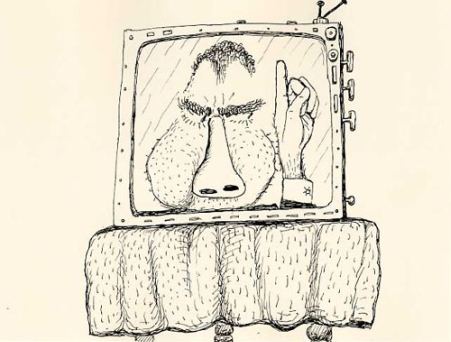

He’s the man firing over his shoulder, the light on his white hat. But because he shot his face in shadow (like a bad guy) and the flesh of his hand flattened, as if it’s pressed against the glass of the TV screen (screaming fake), he revels in his scam. In the heart of the he-man ideal, the hero cuts himself off from the past and charges blindly into the future, where he will, if the camera followed him, fade from view. Beckman’s version doesn’t ring entirely true, and that’s what’s good about it.

He’s the man firing over his shoulder, the light on his white hat. But because he shot his face in shadow (like a bad guy) and the flesh of his hand flattened, as if it’s pressed against the glass of the TV screen (screaming fake), he revels in his scam. In the heart of the he-man ideal, the hero cuts himself off from the past and charges blindly into the future, where he will, if the camera followed him, fade from view. Beckman’s version doesn’t ring entirely true, and that’s what’s good about it.

Through Jan. 30.

Through Jan. 30.

David Nordhal,

David Nordhal,

The artist looks like a mild-mannered nerd, which is why the photos of him knitting his way through his superhero fantasies are compelling.

The artist looks like a mild-mannered nerd, which is why the photos of him knitting his way through his superhero fantasies are compelling. Just dreaming of them works too.

Just dreaming of them works too. Through Feb. 13.

Through Feb. 13.