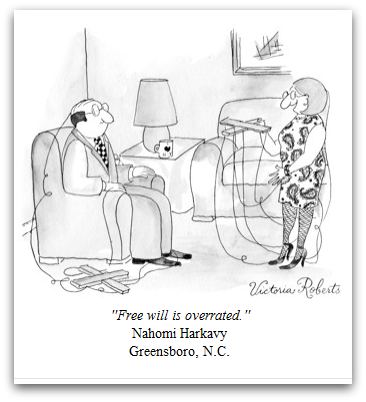

In The New Yorker via email from Douglas Britt, in honor of The Puppet Show at the Frye:

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

In The New Yorker via email from Douglas Britt, in honor of The Puppet Show at the Frye:

Formerly with the real PI, the two-woman force field in food writing, Rebekah Denn and Leslie Kelly, each have their own thriving blogs and related writing projects. That leaves the online PI with a citizen journalist restaurant critic, who in this context works for free.

In mainstream food criticism, if you to eat with a restaurant critic, you’ll get a lecture ahead of time on what not to say and what you’re responsible for ordering.

Critics want to sample the menu without being obvious. The main thing you can’t say? That you’re eating with a restaurant critic. The whole premise of a review falls apart if the restaurant knows a critic is on the premises. The critic will be favored (duh), which means the meals s/he writes about are not the meals served to just anybody. That’s why critics wear big hat and sunglasses in photos, when photos exist at all. They pay cash or use credit cards in somebody else’s name.

This just in from the citizen journalist who now functions as the PI’s restaurant critic. Click restaurants/dining under A&E, and you’ll get him.

Two of my co-workers have basically moved into Volunteer Park Cafe (link added). They work out of the cafe many days out of the week. This adorable little cafe located in an otherwise residential portion of the Capitol Hill neighborhood in Seattle is quite homey, so it’s no surprise they’re making it their workday “home”. In addition, as I joined them and another friend for lunch, after we ordered, one of the “regulars” informed the owner that I’d be writing about my meal.

In addition to all the food we ordered and paid for, a plate of free cookies and cake magically appeared towards the end of our meal. I make it a rule not to let restaurant owners know why I’m there and I pay for my food. I chastised the informer appropriately, but I did eat those cookies.

My general philosophy is that I try to be as fair as possible. I don’t ask for special treatment, and I don’t expect any. That said, I do photograph my food and restaurant folk are not dopes.

His friends didn’t get the shalt-not rap when it mattered, ahead of time, and he photographs his food. Yes indeed. Restaurant folks are not dopes.

Real restaurant critics have their own eccentricities. When he was at the PI, Tom Sietsema, now at the Washington Post, used to follow a few small, well-considered bites of any item by dousing the remainder with salt and pepper. It’s how he ate out almost every night and kept his lovely figure. I believe restaurants in Seattle were on the look-out when waiters cleared plates for those encrusted with condiments. If it was the salad, they could come back big with the entrees and desserts.

When an exhibit is traveling, local venues frequently complement what arrives in crates with what can be carried across town. A Picasso and Matisse, together again, blockbuster? We can add to that. European Impressionism, peak and post? We can match that.

The exception is contemporary. If an exhibit on a contemporary theme is on the road, rare is the regional museum able/willing to integrate the home grown with the imported.

Why? If done badly, it’s better not done. Good examples of Picasso exist lots of places. But faith that artists in a particular region can succeed in a global context is harder to come by.

The Puppet Show from the ICA is a hit at the Frye. That’s great, but why not spread that applause around?

Take Seattle’s Mr. Puppet, Warner Blake, veteran of innumerable street fairs and puppet dinner theaters. No room for his orchestra on the back of a turtle, his suitcase-sized marching band?

It would have been easy to make a little.

Check it out. In my case, he means he tough-loves me. Dave Horsey to me:

Regina, I still love you, even though your comments about me are preposterous.

This post – Dave Horsey derides his former (fired) PI colleagues – remains big in journalism circles, although most of the discussion is not on this blog. But good responses continue to trickle in, from the irritated (Emily White, whom I think might have intended to respond to this post, which referred to her PI tenure) to the amused (Casey Corr).

White was at the PI for (roughly) a hard half-a-year. Corr was on the staff when I showed up in the early 1980s, put in close to a decade and moved on. Point is, Corr and I (and Horsey) go way back.

Corr:

To readers of (Another) Bouncing Ball: I’m going to slip this comment in weeks

after the original posting in the hopes that only readers but not

Regina Hackett see itFirst, I sat next to Regina Hackett

back at the old P-I on Wall Street (where the Globe spun for a reason)

and not once did she say she found me brilliant. So that sets me apart

from Emily White. Regina never even called me semi-smart.Second, Dave

Horsey’s tactic of telling a critic that he loves her is the first

thing he learned on the (University of Washington’s) Daily, back when he and other Dolly

Parton-style big hairs were chasing Charles Odegaard trying to slip out

the back door of the Administration Building at the University of

Washington.In fact, Horsey yelled “I love you” to Odegaard in a

shameless effort to get an exclusive. It worked. Odegaard stopped and

thus Horsey gained his first Pulitzer.As for Horsey saying he loves

Regina Hackett, I can only say, get in line, pal. I loved sitting near

Hackett so much that when I turned coat and went to the Seattle Times,

I graciously allowed Regina to have my old phone number, 448-8332.

(That number now rings into a dictation machine that transcribes

comments into a blog called 8332.)Later, I tried to get Dave to join

me at the Times but he had an understandable concern about the chilly

water that flowed in the veins of the editorial-page editor of that

era. Finally, if ArtsJournal decides to throw a fancy party for its

advertisers, I’m quite willing to give the speech and celebrate the

shock of the new, or the new new thing, or the value of hits or eye

balls, or whatever puts digital journalism on the cutting edge of

cutting costs as the mass medium turns mini, along with the pay checks.Have tux, will travel. Casey Corr

P.S. If by chance, this posting is a

duplicate, I apologize. I got an error message when I tried to post the

first version and lost my draft. The blogging world has its cruelties.

Enjoying a conversation with a hospital security guard who once slammed a man face first into a glass wall for spitting on her, I missed the fact that I’d followed the line out onto Lead Pencil‘s ramp rising on a steep diagonal at Seattle’s Moore Theatre.

I’m afraid of heights. Titled Exit Ramp, the piece cut the theater in half and gave those traveling on it a new view of the space below. What that new view was I can’t say. As my knees locked, I focused on a woman in a wedding dress with gray ashes on her white-washed face who was leaning out from the balcony above and singing Mozart.

The song and the sight of her (old-worldly with a hung-in-the-closet, suppressed glamour), distracted me from an interview that came to mind at this most inopportune moment. In it, Brendan Kiley asked Lead Pencil’s Annie Han about her fears for Exit Ramp.

.

The eternal fear of structural collapse and bodily injury on any

project bigger than a man is tall.

Exit Ramp is part the Free Sheep Foundation‘s Moore Inside Out, a Saturday-night only project with 50 Seattle artists and performers that treated the whole theater as a gallery, including stairs and corridors, basement and backstage.

Thousands showed up. As Kiley wrote in his preview,

Free Sheep roots out forgotten places, their histories and memories,

and distills them into potent, one-shot events that leave indelible

burns on the city’s collective memory. Free Sheep happenings are

mayflies on fire.

Lines curved around the block to get in. Once inside, there was more waiting. Few appeared to have any idea of what they were waiting for. People joined a line and shuffled along in a collective mood of happy-to-be-surprised.

Not everybody, of course. I ran into an art historian who said, “Typical Seattle mediocrities.” She was waiting for her yoga teacher to perform and looked as if she were holding her breath.

The crowd was the thing. Seattle is frequently a place where an audience is hard to come by, which means this audience – everybody there for performance art – was heartening to itself.

Something important got lost in the self-congratulations, however.

[Read more…] about Free Sheep Foundation – Moore Inside Out (Fear of heights)

The new ornate: Kehinde Wiley

The old rough and tumble: Ed Templeton (with stigmata)

The old rough and tumble: Ed Templeton (with stigmata)

Their merger: Debra Baxter – Brass Knuckles/Tongue (Hurts So Good)

Their merger: Debra Baxter – Brass Knuckles/Tongue (Hurts So Good)

In the catalog for The Puppet Show at the Frye (organized by the ICA), John Bell claims that a puppeteer frustrated by his unachievable desire to control people (Being John Malkovich) the “way he controls marionettes…has nothing to do with real puppetry and is instead a misdirected metaphor about puppets: the idea that the goal of puppet performance is complete control of the object.”

The word “complete” saves the sentence, but not by much. Subtle undercurrents are not the ocean. A bottom is not a top, and a puppet directs nobody’s action, not even its own, especially not its own. One person peels the grape, the other eats it: When I say do it, hop to it.

But rules of puppetry are not rules of art. Art is not limited to the taking and/or giving of orders. It’s about doing what you can defend, which is, in this show, to muddy the waters.

Bruce Nauman’s Violent Incident (Man/Woman Segment) is puppet tennis, with actors. If violence is the ball, they bat it back and forth; both victims and aggressors.

Philippe Parreno and Rirkrit Tiravanija use puppets as art world stand-ins. Once artists establish a brand, can’t they disappear inside it, letting their puppets do the interviews? Who’s the puppet in this case, the figure sustained by strings or the journalist taking the interview seriously?

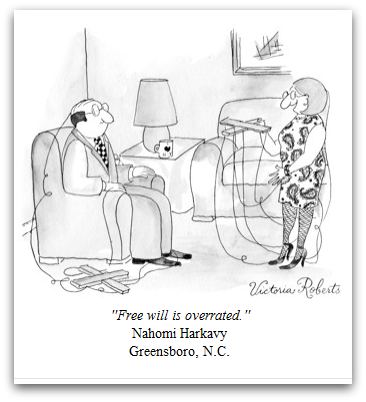

In Guy Ben Ner’s Elia: A Story of an Ostrich Chick (2003), the artist, his wife and two children descend the evolutionary latter to enact a drama that accurately portrays their lives – evolution as a slide guitar.

In Guy Ben Ner’s Elia: A Story of an Ostrich Chick (2003), the artist, his wife and two children descend the evolutionary latter to enact a drama that accurately portrays their lives – evolution as a slide guitar.

In Kara Walker’s Testimony: Narrative of a Negress Burdened by Good Intentions, whites are slaves whom blacks generously claim, only to be exhausted by the whites’ inability to rise to the rudiments of civilized behavior. It’s a shadow play in video, but not a simple exchange of roles. The whites are burdened by white stereotypes. In the end, power does not corrupt, and oppression does not ennoble.

Nayland Blake’s Tabletop Production of the Philosophy in the Bedroom is a history of the old world, its decadence and freedom preserved in fragments. Annette Messager’s Faire Paradeis a pair of child’s pajamas riddled with colored pencils – St Sebastian for preschoolers.

If Pierre Huyghe’s “This is not a time for Dreaming” (with Puppet Heap) were the entire show, it would be worth seeing, even though the narrative cannot be gleaned without explanation. The narrative doesn’t matter. What does is the clear, haunting beauty of each scene as it slides from present to past. Art can break your heart.

If Pierre Huyghe’s “This is not a time for Dreaming” (with Puppet Heap) were the entire show, it would be worth seeing, even though the narrative cannot be gleaned without explanation. The narrative doesn’t matter. What does is the clear, haunting beauty of each scene as it slides from present to past. Art can break your heart.

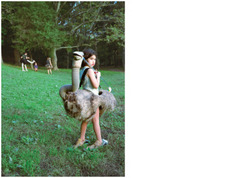

That leaves, among a host of other terrific entries, the obvious one, reproduced on the cover of the catalog and with nearly every review: Dennis Oppenheim’s Theme for a Major Hit (1974).

To answer his own question – how to make performance art without being there? – he created a cadre of his own mini-me’s. Dressed in hip suits, they assume various unruffled positions till a timer goes off and they dance.

Puppets are rarely cool. They’re fall guys who are beat on the head but rise again, bits of their stuffing clinging to the cugel. Oppenheim’s make Andre Benjamin look awkward. They’re light on their feet, with a heavy-metal gleam in their gun-gray eyes.

Jaymi Durate, a Frye guard who’s spent weeks with them, winces when the bell sounds and they thunder into action. She says their charm wears out, and she could be right. Give them five minutes and leave, on the other hand, they’re hot forever. Her best-of-show is Pierre Huyghe.’s. The more you see it, she said, the better it gets.

Jaymi Durate, a Frye guard who’s spent weeks with them, winces when the bell sounds and they thunder into action. She says their charm wears out, and she could be right. Give them five minutes and leave, on the other hand, they’re hot forever. Her best-of-show is Pierre Huyghe.’s. The more you see it, she said, the better it gets.

Because he and his girlfriend just broke up and he remains broken up about it, a guard at the Frye cannot force himself to rotate through the gallery in which Cindy Loehr‘s two-channel video, Colloquy, runs on two monitors.

The Frye has a tight crew. Other guards are covering for him.

He’s not the only one who backs away as if the gallery’s a gun. Loehr’s pair of talking hands with rhinestone eyes and mouths that move in the crack between thumb and palm recite a text that anybody who’s not extraordinarily lucky has already heard and/or spoken.

Only one hand talks, and it’s a massive utterance.

Only one hand talks, and it’s a massive utterance.

In their search for closure, the garrulous cover their targets in wounded projections. They lay out what the other did wrong and how (even now) the rift can be healed (baby, don’t go), if only the silent would speak in confessional detail and profess revived devotion.

Loehr’s silent, soon-to-be ex expresses misery with small, downcast quivers. No frog spreadeagled in a high school biology lab suffers more. The text tells itself through hands manipulated into expression, which makes those hands puppets. The videos that feature them are in The Puppet Show, a traveling exhibit from the ICA.

At the Frye through Sept. 13. Previous here, more to come.

an ArtsJournal blog