At the press preview for the Seattle Art Museum’s small but choice Wyeth exhibit, Remembrance, exhibit curator Patricia Junker said Wyeth was the figure whom the international crew of artists featured in Michael Darling’s Target Practice: Painting Under Attack (1949-78) had in mind.

Both exhibits open tomorrow. (Target Practice reviews to follow.)

Wyeth’s admirers try to insinuate him into the thick of things. For the artists in Target Practice, however, he wasn’t on the firing range. Rauschenberg erased a de Kooning. Andrew Wyeth? His name did not come up.

Wyeth backed himself into a corner of a particular place rooted in land and family and painted his fear of the world. With a desperate and dry exactitude, he documented every inch of what mattered to him. He aimed for sentimentality but didn’t get there.

Wyeth backed himself into a corner of a particular place rooted in land and family and painted his fear of the world. With a desperate and dry exactitude, he documented every inch of what mattered to him. He aimed for sentimentality but didn’t get there.

His idea of the beautiful is dead-on-arrival, but his depiction is the equivalent of Miss Havisham preserving her cake.

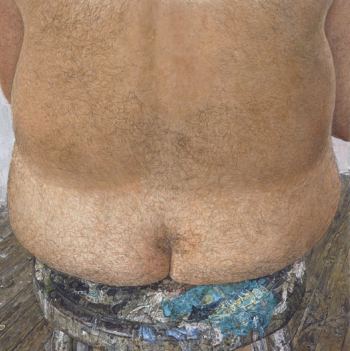

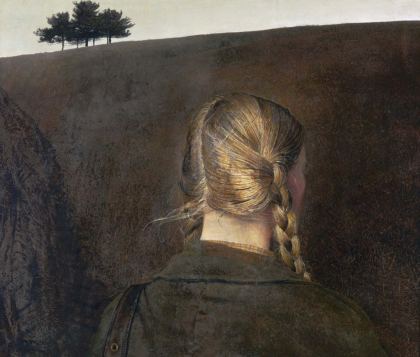

Take Farm Road, above. (1979, Tempera on masonite, 21 inches high by 25 1/4 inches wide. Private collection.) Rembrandt-light shines on the greasy hair of his model, gray and brown at its roots and brass in its braids. Is the farm road in the title the rigid path of her hair? There is no other.

The rusted iron ground that rises in front of her blocks her progress. She’s right where he wants her, under his surveil, every hair on her head counted. Above, where she isn’t looking, the flat light of another dull day rises against a horizon line broken by a cluster of trees.

Wyeth is the American version of Edvard Munch, literal where Munch is flowing but tapping into the same emotional territory. Wyeth’s scream is that there is no scream. He’s the painter of a vast suppression, what it took for him to pass for normal in the countryside.