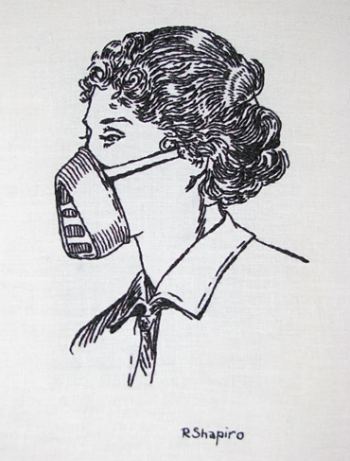

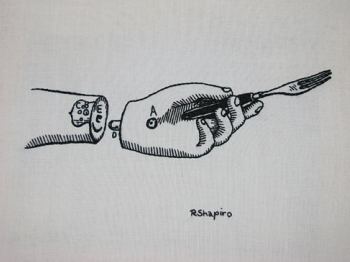

Rebecca Shapiro to the rescue, with embroideries on muslin, via.

If You Held My Breath, You’d Know What It Felt Like

After the war

After the war

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

Rebecca Shapiro to the rescue, with embroideries on muslin, via.

If You Held My Breath, You’d Know What It Felt Like

After the war

After the war

Tyler Green on Bruce Nauman and the reality of torture, here. In the future, if we manage to climb back up the cliff we fell off during the Bush years, people will look to art for evidence that we grasped the horror of our situation. Green’s writing serves as an affirmative:

Nauman’s sculptures were not about the United States. In 1981 Nauman

couldn’t have had any idea that America would become a kind of

modern-day post-colonial force in two occupied states, Iraq and

Afghanistan. He couldn’t know that 20 years on America would become a

nation that engaged in extra-legal detention, a country that stuffed

detainees into private jets so as to whisk them around the world to

places where they could be brutally confined, tortured and, in several

cases, killed. In 1981 Nauman’s sculptures were about what happened to

other people, people such as the Trinidadians, Argentinans, or

Uruguayans in Naipaul and Timmerman. Today I look at Nauman’s two 1981

artworks and I think about what the United States did in its fanatical,

unprincipled pursuit of terrorism suspects and in Iraq and Afghanistan.

One of the things that makes art imperative is this: During its

lifetime it can jump beyond its inspiration to become about us.

911 Media Arts Center moves in with Jack Straw Productions, story Jen Graves. Money quote:

It’s becoming more cloud-like.

911 and Jack Straw have a lot in common. Both are multi-media populist with aesthetic ambition. What they won’t have is any room (or good location or parking). 911’s Steven Vroom, who with Jonh Schwartz constitutes the only 911 Media staff left, has a down-not-out message on his site, here.

Bravo casting call for artists: Here’s the opening paragraph from application instructions:

How do you go from struggling, emerging or even semi-established artist

to selling a complete show for $198 million? It’s a big art world out

there, but maybe this is one place to start!

Far be it from me to piss on anyone’s parade, but people, read those sentences again. Sharon Butler at Two Coats of Paint has the best response:

I’m urging older artists, particularly mothers, to take a shot at it. Bring the kids to the audition, change a diaper or two while waiting in line, and show the dirty ones as work samples. Seriously. At the very least, document the whole experience, upload it to YouTube, and don’t forget to send Two Coats a link.

Good Target Practice: Reviews from Emily Pothast, Jen Graves, Art Knowledge News, e-bourne and Publicola.

From Graves:

(Curator Michael) Darling is not restating a

canon, he’s refining it, bringing together artists from several

continents and pairing lesser-knowns with household names. The arch

sensibility of Pop, the communalism and performance of Brazilian art of

the period, the sunny California renegades, the anarchic Viennese

Actionists, Japanese postatomic hysteria and despair, the quotational

impulse of the pre-Pictures generation, hippie-style madness, the

chilly conceptualists, the early feminists, highly codified and

organized German pain–all these come together in a grouping

that’s different from the classic (and overly cerebral) New

York-centric story of minimalism-and-after. This version of the

story is deliberately visceral.

Choice, but I don’t agree with what followed in the same review:

The first two galleries feel crowded and awkward; the last few, plodding. By the end, at Warhol’s sidelined Oxidation (piss) Painting and Lynda Benglis’s poured-paint piece (did it have to be mounted on a pedestal rather than lying on the floor?), the exhibition has run out of energy.

That’s what diversity of critical voices is all about. Not long ago, Seattle exhibits would be lucky to see one review. If there were two, they either failed to spark discussion or there was no place to air it. As an arts editor at the former Seattle PI once told me, responding is beneath your dignity. (That version of dignity remains in place for most critics who still have jobs at newspapers.)

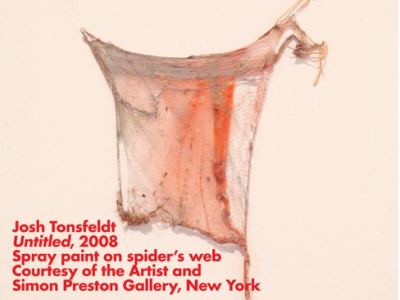

The outer limits of what constitutes a photograph do not include spray paint on a spider’s web, unless its shape minicks a Polaroid gone to seed. By asserting itself outside the definition, Josh Tonsfeldt‘s web expands the category to include it.

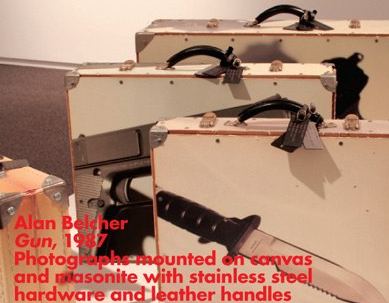

Curated by Bob Nickas for Vancouver’s Presentation House Gallery, phot(o)objects made a seamless leap from nonprofit to commercial space, setting up shop at Lawrimore Project.

Curated by Bob Nickas for Vancouver’s Presentation House Gallery, phot(o)objects made a seamless leap from nonprofit to commercial space, setting up shop at Lawrimore Project.

If the audience were frequently in motion from Portland to Seattle and Vancouver, a Seattle stop for a Vancouver exhibit wouldn’t make sense. Everyone inclined to see it would have.

Alas. Not the case. Determined not to wait for a bullet train, Scott Lawrimore is doing what he can to strengthen the links between cities that have everything in common except the reality of free exchange. Exhibits important in one city rarely register in another, which makes phot(o)object a welcome exception.

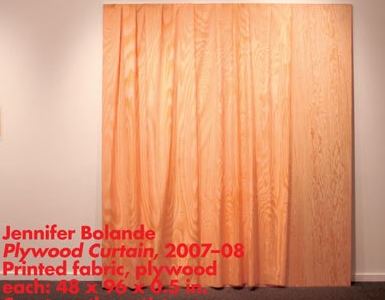

Jennifer Bolande transformed the mass-produced visible with a curtain that bears a photographic image and impersonates carved wood.

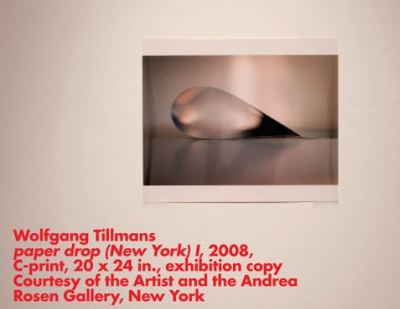

Wolfgang Tillmans inserts a false memory of a classic photography moment.

Twenty artists, not a dud in the group. Through Aug. 1.

Veteran of Helter Skelter at MOCA in 1992 and the 1999 Venice Biennale, Los Angeles painter Richard Jackson participates in Target Practice: Painting Under Attack 1949-78 at the Seattle Art Museum (review here) by pouring paint on canvases and smearing them in arcs on a museum wall. They comprise something like a painting tornado, with a passage of dead white calm at their center.

SAM documented the process on YouTube.

Jackson explains, via:

It is my idea to try to expand painting, not just in size but to see how far it could be extended or pushed. I don’t feel my work as a criticism of painting but an optimistic view of what it could be. I felt then and I still feel that painting doesn’t need to be an area of art described by the materials that are used …My work doesn’t edit anything, it’s evidence of a work performed…

Jackson began by emulating the Action Painters of the New York School and kept on working in that vein, which took him other places. He works with the accidental but is absolutely in charge of the process. I’ll think of his painting whenever I see a younger generation’s paint leaking into space with vigor and intention.

Why is this image smoking, while countless others featuring falling down barns are born stone cold dead? Renaldi’s absence of nostalgia. His image is a clean hit.

Why is this image smoking, while countless others featuring falling down barns are born stone cold dead? Renaldi’s absence of nostalgia. His image is a clean hit.

The title of this post comes from the 20th-century’s most influential poem, Yeats’ The Second Coming:

TURNING and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

Sherman Alexie’s Web site is titled, Falls Apart. Joan Didion’s breakthrough essay collection? Slouching Toward Bethlehem. And

Chinua Achebe’s best novel, the African version of King Lear? Things Fall Apart. The first 8 years of the 21st century suggested an answer to the poem’s last line. What beast slouches toward Bethlehem? We do.

My ride is the kingdom of God. Via

On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog, but if you bark, beg, drool and growl, people figure it out. Once acquired, can that identity be shed?

Troy Gua is interested in character that can assumed, rejected, fictionalized, asserted and deleted online on social networks, blogs, fan sites and chat rooms. What part can be claimed as easily as picking somebody else’s coat from a cloakroom, and what is hardwired as a fingerprint?

He’s at Vermillion through Aug. 7.

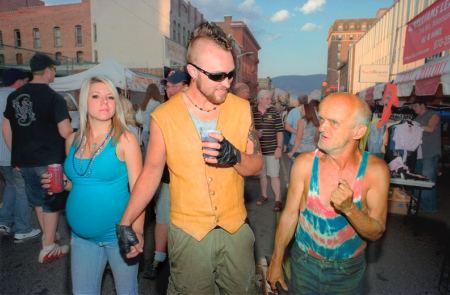

As a tribute to Garry Winogrand’s 1981 series, Women Are Beautiful, Alice Wheeler created her own collection of beautiful women. Her exhibit at Greg Kucera is the first foray for the series, which is ongoing.

Unlike Winogrand, Wheeler is not looking at the other. Plus, her definition

of the beautiful is far more generous than Winogrand’s. He focused on

the affluent, urban young. She includes the rural, the old, the flaky

and defiant, as well as those Winogrand would agree are lovely by

anyone’s measure.

The Winogrand-Wheeler connection is the sweep of a moment in motion, a fragment from life’s random stream that speaks volumes about the whole.

The Winogrand-Wheeler connection is the sweep of a moment in motion, a fragment from life’s random stream that speaks volumes about the whole.

Women own their space in Wheeler’s work. Even when they are clearly being steered by a man through a scene not their own, their contact with Wheeler is electric.

Nan Goldin comes to mind, for good reason. Almost everybody working on the fierce end of the sexual vibe owes her, but if Goldin’s and Wheeler’s prints were in the same show, the differences would be apparent.

Nan Goldin comes to mind, for good reason. Almost everybody working on the fierce end of the sexual vibe owes her, but if Goldin’s and Wheeler’s prints were in the same show, the differences would be apparent.

Wheeler is heads-up play. There’s an upbeat, irrepressible refusal to judge in her work, a determination not to call anybody a freak, unless as a compliment, and an inability to accept a depressing scene as a downer. She’s the kind of person who’d read The Metamorphosis and think it’s a comedy.

In the photo above, PREGNANT WOMAN AT EVIL KNIEVEL DAYS, BUTTE, MT (2007), the man on the right looks as if he slipped out of a Matthias Grunewald to join the festivities. In Wheeler’s hands, he’s no longer an outsider. In her work, all the outs are in free.

an ArtsJournal blog