…can go to sea.

Kassandra, via

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

Ulli Weiss photo from Pina Bausch performance

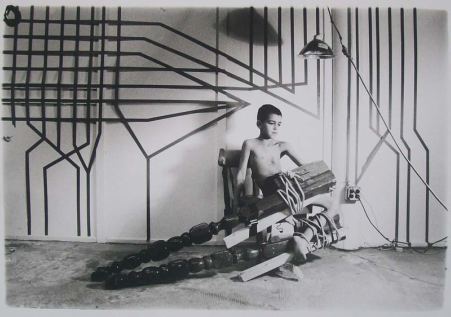

Sean M. Johnson, Family Portrait (Nothing but tape holding it to the wall)

Sean M. Johnson, Family Portrait (Nothing but tape holding it to the wall)

If you start here

or here

or here

you can stop here

you can stop here

with a leapfrog to Trimpin and Christian Marclay without missing much in between.

with a leapfrog to Trimpin and Christian Marclay without missing much in between.

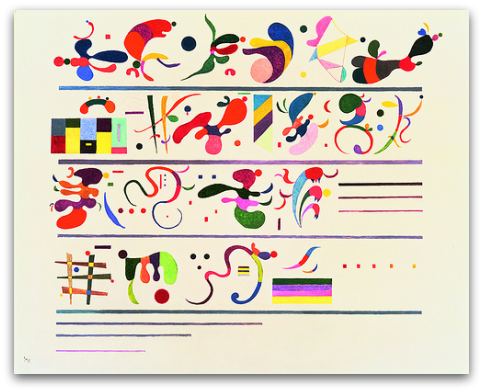

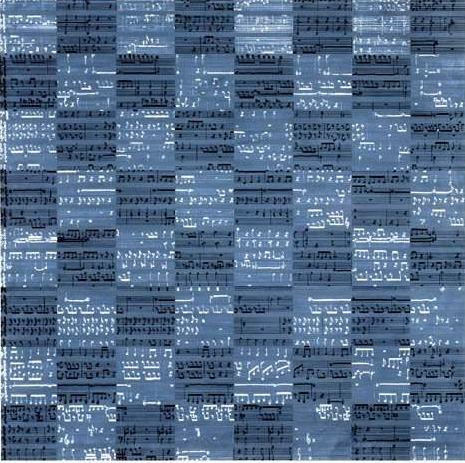

Minus the mysticism, Trimpin and Marclay are as committed as Kandinsky to the visual implications of sound. While many of Kandinsky’s ideas about spiritual color and visual sound found few takers in the second half of the 20th century, they are in play today.

Trimpin– Score for PHFFFT

I remember as a child helping to build huge, wooden discs to set on

fire at night and roll off a ramp to hang in the air and fall into the

valley below, as part of an old German festival. I heard the whistling

and crackling of the wet wood as it rolled down the ramp and thought of

opera. I asked the other boys, `Do you hear that?’ They said no. I like

to think my work enables other people to hear what I hear.

I composed a

silent collage of found film footage partially layered with computer

graphics

to provide a framework in which live music can develop. Moving images

and

graphics give musicians visual cues suggesting emotion, energy, rhythm,

pitch,

volume, and duration. I believe in the power of images to evoke sound.

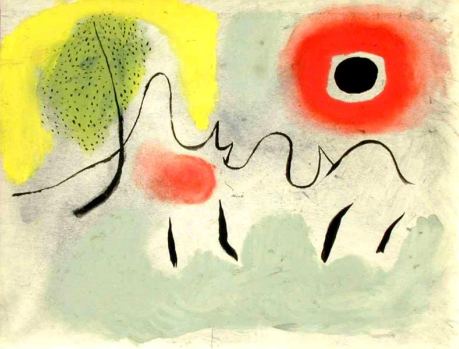

Image from Marclay’s Screen Play

Tim Roda comes from a family of makers. His Italian-immigrant grandfather and father built the family home out of the same scrap and recycled wood with which they

built their chicken coop.

My father built a two-car garage whose

three sides look like a patchwork quilt of various wood surfaces and

textures. Although I used to question my father and grandfather’s way

of building and “fixing” things, I now recognize and embrace this style

not simply as a legacy but as an hereditary fingerprint.

As a father himself, Roda is intent on passing on the scrap aesthetic that made his home distinctive from his neighbors. His oldest son Ethan has acted in his father’s fantasies since he was a toddler. Ethan’s grace makes those fantasies credible within improvised clutter of his father’s stage sets.

Perfection is attainable in photography. Those who pay for equipment can achieve pristine results at the press of a button. Roda’s are rough.

The rough edges, erratic fixer stains, and haphazard tonal range are

suggestive of the working class way of life my grandfather experienced

when he came to America as an Italian immigrant. This set of values was

passed down to my father and then to me with all of its eccentricities.

From mythical beast to the Children’s Crusade, weapons are crucial to the tale.

Artists find models in their families, but the idea of collaborations between partners was rare before the early 20th century, most famously between

Artists find models in their families, but the idea of collaborations between partners was rare before the early 20th century, most famously between

Robert and Sonia Delaunay, who had separate careers but shared ideas

for each other’s projects.

Although Christo and his wife, Jeanne-Claude, began working together soon after

they met, the full extent of her contribution wasn’t acknowledged

for several decades.

Children enter the picture with the Boyle Family. Mark Boyle created his work in sync with his wife,

Joan Hills, and eventually decided to share a credit line not only with

her but with their adult children, Sebastian and Georgia.

Some women married into major art careers, such as the late Coosje van

Bruggen, who married Claes Oldenburg; or Nancy Reddin, married to the

late Ed Kienholz. Both couples signed their joint names to work

produced after they set up housekeeping, although the fundamentals of

style were grounded in the husbands’ aesthetic.

Sally

Mann, Ralph Eugene Meatyard and Emmet Gowin all created tableaus

featuring their offspring. In Seattle, Zack Bent‘s staged shots grow out of what his kids feel like doing or what they do accidentally, within the context of throwing a ball, building a fort,

helping with chores, wrestling and playing in the yard.

For high family theatrics, nobody beats the videos of Guy Ben-Ner or the photographs of Tim Roda. In the latter’s exhibit at Greg Kucera, the high jinx of earlier work is largely gone, replaced by a darker tone.

The photo below is untitled, but if it came with text, it might be: Lamb of God, who takest away the sins of the world, have mercy on us. We ask this even as we kill the Lamb. In its slaugher is our redemption.

Below, the child is again ensnared by emblems of Catholicism. The legs of an ornate table become a heavy loop of rosary beads, and the planks of wood serve as the foundation for a Cross within an overbearing grid of rules.

Below, the child is again ensnared by emblems of Catholicism. The legs of an ornate table become a heavy loop of rosary beads, and the planks of wood serve as the foundation for a Cross within an overbearing grid of rules.

Through Nov. 14.

Through Nov. 14.

Except when it isn’t.

“Devastating” cuts in British Columbia literary circles here, from the Globe & Mail.

Previous on this blog, the effect of similar cuts to B.C. visual art groups, here and here.

U.S. artists exhibiting in B.C. are frequently stunned by the support offered. They are paid to participate in group shows at galleries. In the U.S., government funding doesn’t carry art culture. Culture has to sell itself to the audience.

Because B.C. museums and galleries know they can count on hefty support, they are free to mount exhibits that don’t have to appeal to a wide, general public. B.C. artists are famed for their brand of conceptual photography. They produced it without the necessity of selling it, because public funding offered them a funding floor.

I love that model, but what happens when the government in power at any given moment is impressed by the sink-or-swim U.S. approach and greatly curtails the cash? Devastation.

The convention of calling cards become entrepreneurial in the 20th century. Because the leisure class no longer wanted to admit it had time on its hands, its cards advertised not free time but the lack of it. Everybody acquired a title, and everybody was working.

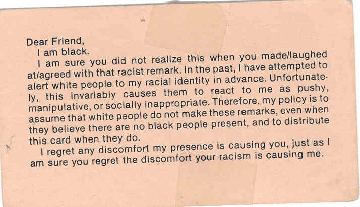

From 1986 to 1990, Adrian Piper returned the calling card to the personal realm, although nobody mistook hers for its gilt-edged predecessors. As a light-skinned black woman, she found herself in conversations that participants had wrongly assumed were whites-only. Hence, her cards, via:

Now, from anewdesigns

Now, from anewdesigns

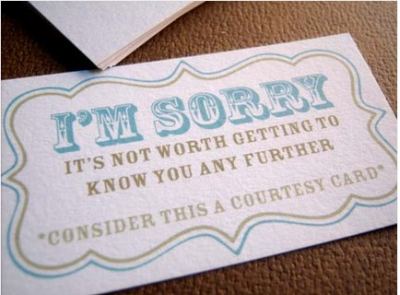

, comes the cad card, via This Isn’t Happiness.

Ran Ortner, who won the $250,000 ArtPrize in Grand Rapids for a painting of the sea, Open Water, could have painted it in 19th-century Russia.

Back then, however, he wouldn’t have been tapped for the top take-away. Even casual observers would have noted what he owes to Ivan Aivazovsky, whose massive paintings of the churning sea go on and on. Aivazovsky would get the cash while Ortner got applause for his skill. Historians would have tagged his work as “in the school of.”

Back then, however, he wouldn’t have been tapped for the top take-away. Even casual observers would have noted what he owes to Ivan Aivazovsky, whose massive paintings of the churning sea go on and on. Aivazovsky would get the cash while Ortner got applause for his skill. Historians would have tagged his work as “in the school of.”

Meanwhile, the Financial Times notes a trend juxtaposing historical and contemporary art:

Meanwhile, the Financial Times notes a trend juxtaposing historical and contemporary art:

October 8 sees the London gallery Robilant + Voena unveiling a show in which young British school artists respond to Old Master paintings. Most have been commissioned for the show and include some startling juxtapositions. A dreamy, sensuous piece by Old Master Ary Scheffer has inspired Tom Gallant to make a flowing paper collage like a fluttering of scarves. Paul Morrison has created “Ilex” (2009), a bold silver-on-linen work that reprises the exploding volcano in Pierre-Jacques Volaire’s fiery “Eruption of Vesuvius at Night” (about 1777) and Alexis Teplin’s brightly-coloured oval abstract painting echoes François Boucher’s “Venus Restraining Cupid” (1762). Prices range from £1,800 to £28,000 for the contemporary works, and from £50,000 to £1m for the Old Masters, who include Meissonnier, Carlo Dolci and Nicolas Tournier.

Previous post on related subject: Art Grants: Foolish peaks and absurd valleys.

In Seattle, PONCHO has a great rep. Since its founding in 1963, it has raised $34 million for 200 or so arts organizations. In recent years, as part of a thank-you to artists contributing to its annual auction, PONCHO singles one out for an “Artist of the Year Award,” chosen by vote from other artist participants.

Although it’s an award given more for community service than aesthetic achievement, winners from previous years have tended to be a distinguished lot, including Jacob Lawrence & Gwen Knight, Fay Jones and Juan Alonso.

This year, artists say, PONCHO found another way to select the winner, other than peer vote. And this year, the winner is Judith Kindler, who happens to be on PONCHO”s board of trustees. For me, her paintings belong in that category of visual nicety that dominates what’s on view in galleries around the country, but that’s not the point.

The point is, PONCHO bypassed peer opinion to select a board member. Kindler might have won anyway, had artists voted, but she shouldn’t have been a candidate. She’s a board member. PONCHO relies on its reputation, and this kind of thing doesn’t help.

Calls to PONCHO have not yet been returned. Will update with its response, if I get one.

Update: Jeff Crandall, who works on the annual auction, defended this year’s change of policy.

“We had problems with artists asking their friends to vote for them,” he said. Instead, PONCHO asked a group of people who are not on the board to make the selection, which comes with a $5,000 prize. He said he couldn’t say who was on the selection committee because PONCHO didn’t want them to “get pressure.”

This year, for the first time, there was a no-cash artists’ choice award that went to Rick Araluce. Crandall also noted that Kindler is no longer on the board although she’s still listed as a member on PONCHO’s Web site . She left in September, after she was picked for the award, he said.

Remember when the Olympic Sculpture Park opened and visitors were shocked, shocked, that the Seattle Art Museum asked them not to touch the art?

The Onion has a fabulous satire on the subject, via Culture Monster.

Gerard Schmidt, a retired banker who lives near the Met, said he had never much cared for museums until he was given the chance to manhandle one of Monet’s Water Lilies.

“At first it just looked like a picture of a bunch of lily pads, but then I started scraping at it with my pocket knife and the whole painting just sort of spoke to me,” Schmidt said. “For the first time, I finally understand what Monet was trying to get across in her work.”

an ArtsJournal blog