Archives for December 2009

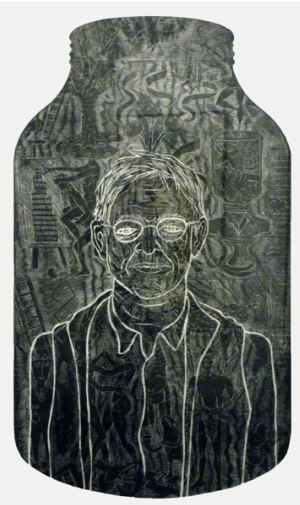

R.I.P. Thomas Hoving – the populist elite

Thomas Hoving was a one-of-a-kind museum director. After him, directors split into two camps: the populists primarily concerned with what plays at the gate and the gatekeepers, determined to preserve their idea of aesthetic standards.

He died today at age 78. (Randy Kennedy obit here.)

He invented the blockbuster but was most proud of his ability to spot a fake. He’d freely admit that he sympathized more with forgers than with the collectors and museum professionals they fooled. In False Impressions: The Hunt for Big Time Art Fakes, he wrote about a favorite, Frank X. Kelly, whom Hoving met while an

undergraduate. A painting restorer, Kelly played the horses, knew

baseball like the beating of his own heart, smoked constantly, ate

badly and made art fakes.

Hoving found some unfinished Monets in the stacks and

confronted him. The old man promised to teach Hoving his trade secrets

if the young man kept quiet. Hoving learned that a good fake looks

juicier, more appealing, than the original. The surface only mattered,

as deeper analysis produced conflicting information. Cooking up a

complicated provenance for the piece was unnecessary and often made the

deal more suspicious.

On tour for the book in Seattle, he took care to be quotable. Choice samples from a 1996 interview here.

On museum directors:

They’re muddled progressives, staunch conservatives or the petrified. Especially the petrified. I don’t think they have any idea what they’re doing. I was director (at the Met) from 1967 to 1978. That’s too long. Directors should get out after seven years. After that, they’re either too tired or too gutless to do the job.

On fakes:

Everybody wants to believe they’ll find a Ming vase at a flea market, pay $1.89 for it and sell it for $1 million. There are serious collectors who’ve fallen for Degas pastels painted in oils. They can’t tell. And when they find out, they cover it up.

On his contribution:

I’m a popularizer. I opened the place up. I wanted to see John Travolta pick up girls on the steps of the Met. I tried to make the Met a subway stop. I was the first to hang big banners outside. Our audience was old and the audience at the Museum of Modern Art was young. I wanted to steal Modern’s audience.

Here’s a 2008 video of Hoving lavishing praise on Dale Chihuly.

Heide Hinrichs – a light touch

Fuse Eva Hesse with Richard Tuttle and you’ve in Heide Hinrichs territory. She has Hesse’s love of the ungainly protuberance and the heavy edit of Tuttle’s subtlety. In my mother’s darker moments, she liked to say, “I wish they’d drop the bomb so we could go underground.” Hinrichs is an artist of the solitary’s apocalypse. Those who stagger back into the light after losing everything would be lucky to find her sculptures on the floor, the flayed skin of soccer ball bladders hung on a wire or deflated inner tubes curled as if smoked in a fire.

Born in Germany and currently living in Seattle, she is the subject of a solo exhibit curated by Marisa Sanchez at the Seattle Art Museum, part of a series titled SAM NEXT, whose focus is alternatively regional and international.

The objects in this show, both found and fabricated, collectively create a kind of landscape. There is solace in its silence, a quiet that enfolded the viewer who walks inside it. A few weeks ago, I saw a small group of rowdy middle-schoolers enter and respond, their hush a tribute.

The objects in this show, both found and fabricated, collectively create a kind of landscape. There is solace in its silence, a quiet that enfolded the viewer who walks inside it. A few weeks ago, I saw a small group of rowdy middle-schoolers enter and respond, their hush a tribute.

Through June 13.

The art of eating badly

In Gold Rush, Charlie Chaplin dined on the sole of a shoe. Not to be outdone, contemporary artists offer a range of similarly dubious treats. (We’re a long way from Dutch still lifes.)

I sneak a cream of wheat sandwich and stale sweet roll, wash it down with juice squeezed from a leather belt.

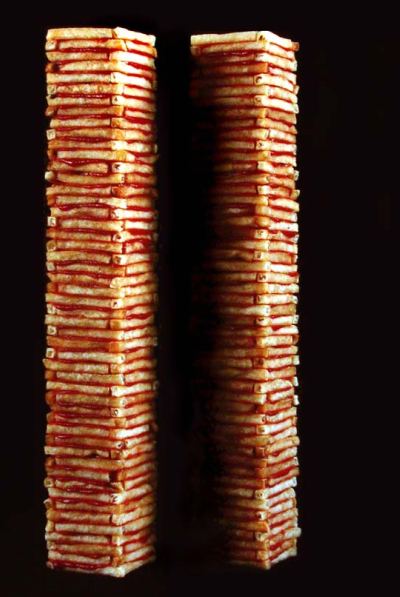

For the fast food crowd who can overlook an indictment as long as it comes with ketchup, there’s Jack Daws’ memorial for the World Trade Center.

TWO TOWERS, 2003

Chromogenic print of artist-made construction from McDonald’s French fries and Heinz ketchup

photographed by Richard Nichol

50 x 40 inches, Ed/10

For those whose culinary standards are a little higher, Dan Webb provides a Feast.

For those whose culinary standards are a little higher, Dan Webb provides a Feast.

For dessert, Greely Myatt has the cake. (More on Myatt from Nicole Griffin on SOAP.)

For dessert, Greely Myatt has the cake. (More on Myatt from Nicole Griffin on SOAP.)

Peter Shelton’s thunder thighs

Ted Bundy for the holidays

Lawrimore Project is offering a range of art objects as holiday gifts, priced under $1,000. It’s the gallery’s idea of a joke. Every gallery in Seattle has something under four figures. But the joke doesn’t end there. One of Lawrimore’s featured objects is Eli Hansen’s To Your Health Untitled (tincture), 2009, a small, clear glass bottle that serves as a portrait of Tacoma.

Containing chips of Western red cedar, soil from Port Madison and brick fragments from Ted Bundy’s childhood home, it’s a $600 portrait of small town noir. Who wouldn’t want a little Ted Bundy for the holidays?

Zoe Strauss had a similar take on Tacoma when she was in town.

Zoe Strauss had a similar take on Tacoma when she was in town.

The recession has been a long dry run. Note to those who are flush: Time to support a gallery or two.

The recession has been a long dry run. Note to those who are flush: Time to support a gallery or two.

William T. Wiley – objects of scorn

Wiley was the William Powhida in the 1960s, before Powhida was born. Like Powhida a master of line, Wiley’s sympathies are underdog, even though he’s not blind to mange, fleas and failure.

Wiley’s Slant Step from 1966 bears this inscription:

this piece is dedicated

to all the despised unknown unloved people objects ideas that just don’t make it and never will, who have so thoughtlessly given their time and talent to become objects of scorn but maintain an innocent ignorance and never realize that you hate them.

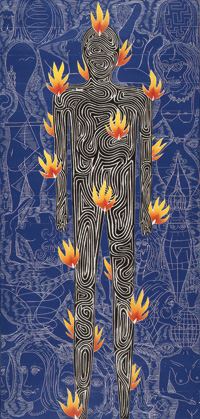

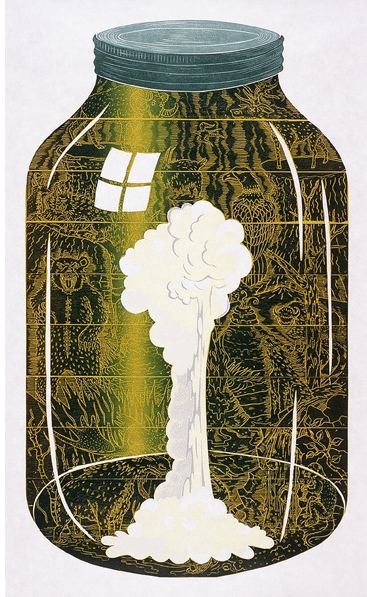

John Buck – message in a bottle

John Buck carves carnival worlds. Press his foot pedal to see heads of famous artists revolve with their

paintbrushes, their dripping watches and their trains coming out of

their foreheads.

Dividing his time between Montana and Hawaii, he favors a fast-growing white wood found in Hawaii and known as

Malaysian jelutong. Similar to cottonwood, jelutong is soft and pliant.

Each of Buck’s rough, chisel cuts eats into the wood and creates small

ripples of disturbance across the surface.

No matter how precise and detailed his carving becomes, it’s never

fussy or anonymous. Evidence of the artist’s hand is always there,

recorded in ragged little stabs.

A survey of his prints (with some paintings) is at the Bellevue Arts Museum, curated by Stefano Catalani from the collection of Portland’s Jordan D. Schnitzer.

Aside from carving, woodcuts are Buck’s strong suit, well represented here. The boldly articulated central figures are surrounded by knotted coils of representation that appear to derive from William T. Wiley. What is comic frenzy in Wiley becomes for Buck a crazy world sealed in a bottle and seen at an austere remove.

Through Feb. 28.

Through Feb. 28.

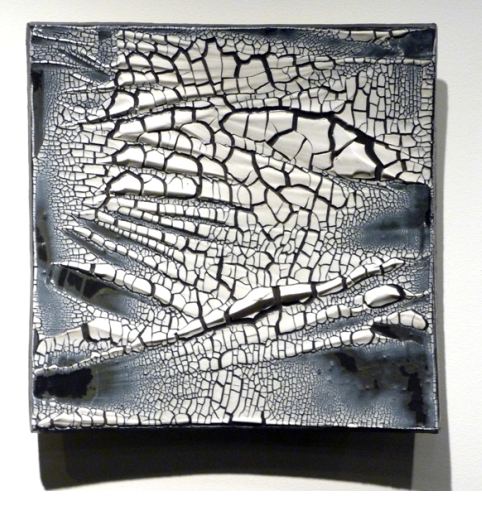

Robert Sperry – mud and foam

Sometime in the early 1990s I ran into Robert Sperry (1927 – 1998) in Oaxaco and commented on the brightness of his shoes, remarkable in a dusty town. His wife, Patti Warashina, rolled her eyes. Turns out, because there were half a dozen kids with shoe shine boxes in the town square and Sperry couldn’t bear to favor only one with his trade, every day he gave all a turn, big tip added. The day I saw him, a boy had lined up for seconds, but Sperry recognized him and said, “You already shined them.” In response, the boy spit on Sperry’s shoes and said, “Now they need another one.” Because the jokes he liked best tended to be at his expense, it was Sperry’s favorite story from his trip.

Untitled, Clay and glaze, 1983

His retrospective, Bright Abyss, is at the Bellevue Arts Museum curated by Stefano Catalani and accompanied by a 270-page catalog with full color illustrations, written by Matthew Kangas. In light of the fact that catalogs are getting harder to find (the Seattle Art Museum’s astonishing Calder show doesn’t have one, for instance), BAM’s commitment to full service is admirable.

His retrospective, Bright Abyss, is at the Bellevue Arts Museum curated by Stefano Catalani and accompanied by a 270-page catalog with full color illustrations, written by Matthew Kangas. In light of the fact that catalogs are getting harder to find (the Seattle Art Museum’s astonishing Calder show doesn’t have one, for instance), BAM’s commitment to full service is admirable.

Untitled, Stoneware with slip

With Warashina and Howard

With Warashina and Howard

Kottler, Sperry created a ceramics department at the University of

Washington that captured nationwide recognition.

Big thanks to BAM for this show, even though it sits in the museum’s dread second floor, curling out of dark galleries into dark hallways. The only adequate gallery spaces at BAM are on the third floor, currently housing an exhibit of John Buck’s woodcuts. I would have reversed these shows, as woodcuts are harder to ruin. Just hang them up in a line and turn on the lights.

At the very least, BAM could have painted the second floor galleries white. Matching gallery walls with colors from the art is a bad decorator’s trick. Sperry is dark enough already.

He was an artist with one big idea. Unfortunately, the exhibit generously samples all his ideas, diluting their impact. (As a filmmaker, he was an academic documentarian. As a funk artist, unlike Warashina and Kottler, he was an also-ran.)

In a Sperry retrospective, the strongest work needs to be like the rabbit swallowed whole by a snake, a huge bulge with flattened representations of other things at either end. Wouldn’t it be better to leave out funk, film, prints and public art models? When presenting an artist whom a lot of people even in the Northwest have already forgotten, hit us with your best shot. Sperry deserves nothing less.

Untitled, Stoneware, black glaze, white slip, 1986

His glory is his mud and foam, his crackled white slip on ash-gray stoneware plates, platters and ceramic tiles. The force of gesture

His glory is his mud and foam, his crackled white slip on ash-gray stoneware plates, platters and ceramic tiles. The force of gesture

frozen on the surface distills both freedom and a certain kind of Asian

restraint. Within narrow restraints, he opened up a range of

aesthetic possibilities, usually in flat gray under cracked white but sometimes gold patterned with white.

Platter

glaze, crackle glaze 1975

Through Jan. 31.

Through Jan. 31.

John Storrs to John Buck

John Storrs, Forms in Space, 1927 Stainless steel and copper

20 1/2 x 4 x 5/8 in. (52.1 x 10.2 x 4.1 cm)

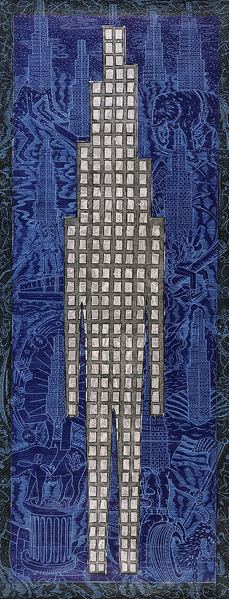

John Buck,

John Buck,

Skyline edition 4/15

2000 – 2002

Four-color woodcut

92 x 37 in. In his exhibit at the Bellevue Arts Museum through Feb. 28.