Justin Swinburne, what looks like concrete and tar as a pillow, trailing stuffing:

The peerless Boyle Family. Not photographs. Random pieces of random streets recreated as sculptures on the wall.

The peerless Boyle Family. Not photographs. Random pieces of random streets recreated as sculptures on the wall.

(Image via)

(Image via)

(Image via)

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

Justin Swinburne, what looks like concrete and tar as a pillow, trailing stuffing:

The peerless Boyle Family. Not photographs. Random pieces of random streets recreated as sculptures on the wall.

The peerless Boyle Family. Not photographs. Random pieces of random streets recreated as sculptures on the wall.

(Image via)

(Image via)

(Image via)

No helmet necessary. (via)

From Kenneth Baker, SF Chronicle:

Contemporary visual artists see opportunity in what many bemoan as the twilight of the age of the book. John Latham (1921-2006), Hubertus Gojowczyk, Doug Beube and others have treated books as sculptural stuff. But no one whose work I have seen tops that of Atlanta artist Brian Dettmer at Toomey Tourell.

In the mural-scale wall piece “Americana” (2009), Dettmer has carved up and layered the volumes of a vintage encyclopedia to produce something kaleidoscopic. World maps in polar hemispheric projection punctuate the array, with an occluding effect reminiscent of the changing images on an old View-Master. (more)

Dettmer was featured this year in the Book Borrowers at the Bellevue Arts Museum.

Alexander Calder, opening at the Seattle Art Museum Oct. 15, A Balancing Act, including:

Not in the show: Jennifer Zwick:

Not in the show: Jennifer Zwick:

Fascism is not fascinating in art, the sole exception being Renato Bertelli’s Continuous profile of Mussolini) from

1933, manufactured by Ditta Effeffe with Mussolini’s approval. (Image credit plus story here.)

Aside from the Linda Blair head spin in The Exorcist (evil, evil, evil), the idea of a mind moving a head in directions its physical structure did not intend persists in art as philosophical speculation. Will the real head please stand up? (What real head?)

Aside from the Linda Blair head spin in The Exorcist (evil, evil, evil), the idea of a mind moving a head in directions its physical structure did not intend persists in art as philosophical speculation. Will the real head please stand up? (What real head?)

From 1989, Buster Simpson’s Seattle George Monument is an emblem of the city’s divided heart.

Twenty-eight feet tall and 12 feet in diameter, its base is a trellis

or open cube, above which hangs a Boeing 707 nose cone suspended on a

tripod. Just above the cone is a multifaceted monument head – 24

aluminum profiles of Chief Seattle, an armature for

English ivy. A sharpened template turning in the wind cuts the

ivy into Washington’s profile, which, when the ivy thickens, hides Chief Seattle in the greenery.

From 1999, Kumi Yamashita’s Video of Dialogue.

From 1999, Kumi Yamashita’s Video of Dialogue.

From 2005, Tim Noble & Sue Webster, Spinning Heads, (via)

Tony Cragg (image via)

Tony Cragg (image via)

To evoke a burning candle, Barry X Ball (via)

To evoke a burning candle, Barry X Ball (via)

From 2007, memory merges you with others. Sherry Markovitz, Mothers and Daughters. (via)

From 2007, memory merges you with others. Sherry Markovitz, Mothers and Daughters. (via)

Time’s inconsistent personal arc, Ari Young’s portrait of Michael C. McMillen, (via)

Time’s inconsistent personal arc, Ari Young’s portrait of Michael C. McMillen, (via)

Jackie Anderson, via

Jackie Anderson, via

From 1996, sometimes the two of you are stuck with each other. Johan Urban Bergquist (via)

From 1996, sometimes the two of you are stuck with each other. Johan Urban Bergquist (via)

Which makes it hard to get through the day. Harold Haydon, Untitled, 1946. (via)

Which makes it hard to get through the day. Harold Haydon, Untitled, 1946. (via)

Alexandra Horowitz’s Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know

draws on that of an early-20th-century German biologist, Jakob von Uexküll, who proposed that “anyone who wants to understand the life of an animal must begin by considering what he called their umvelt . . . : their subjective or ‘self-world.’ ” Hard as we may try, a dog’s-eye view is not immediately accessible to us, however, for we reside within our own umwelt, our own self-world bubble, which clouds our vision. (more)

Seattle photographer Ford Gilbreath cracked the canine umwelt in 2000 with a series shot from its point of view.

Just my own naked self and the stars breathing down, it’s beautiful.

Some artists are expected to die young. Hats off to Jim Carroll, one of their number. He stuck with it into his 60s and died last Friday, not of his volition.

If only Dash Snow had followed his excellent example. (Image via)

Among many others, Seattle poet Jesse Bernstein could have used more time.

Among many others, Seattle poet Jesse Bernstein could have used more time.

More Noise, Please!

I live on a street

where there are many

many cars

and trucks

and factories

that pump

and bang and

grind all night

and day.

It is a miracle

that I can write poetry

or sleep or

talk on the telephone

or that

my lover will

visit me here

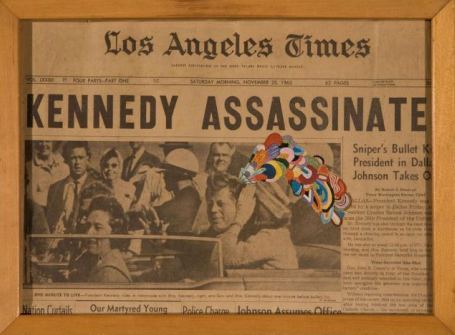

Bean Gilsdorf at Linfield College through Oct. 10. The horror of it all.

Now that baroque portraits of excrement can be found hanging in luxury condos, why does bad painting on black velvet continue to deliver an outsider punch? Bad painting alone doesn’t do it. Marcia Tucker brought it into the mainstream in 1978. It’s the velvet, with paint congealing on its furry nap.

In the velvet realm, everyone’s a star or at least can gather together with others who are equally inept to become one: volume, volume, volume. Velvet in quantity dispenses with the notion of quality. Case in point, Velveteria in Portland, which attracts more national attention than any other museum in the region.

Seattle made a stab at a black velvet painting museum (Villa Velour) in the late 1990s, which still exists online. It went wrong by focusing on the classical best in bad velvet. (Cynthia Rose story here.)

Where does this leave more conventionally-defined good painters, as opposed to a version held by the velvet underground? If they’re willing to be nappy, they’re looking good. The mainstream is unlikely to embrace the racist, sexist cornball Edgar William Leeteg (see Villa Velour link), but others who add just a touch of Leeteg can ride out of time to a mythical carny world.

Did I ever tell you the story of the twentieth-century man in a third-century church, his hand resting on an eighteenth-century banister?

No, but when he tells his tales on velvet, he has everyone’s attention.

Schnabel, Portrait of Andy Warhol, 1982, oil/velvet, via.

Colored velvet works if you’re Polly Apfelbaum… (Image via)

Colored velvet works if you’re Polly Apfelbaum… (Image via)

Or Claudia Fitch. (sculpture covered in blue flocking, which is velvet’s tighter twin. Image via)

Or Claudia Fitch. (sculpture covered in blue flocking, which is velvet’s tighter twin. Image via)

Can a shaggy version of velvet ride its coattails? (Misako Inaoka)

Can a shaggy version of velvet ride its coattails? (Misako Inaoka)

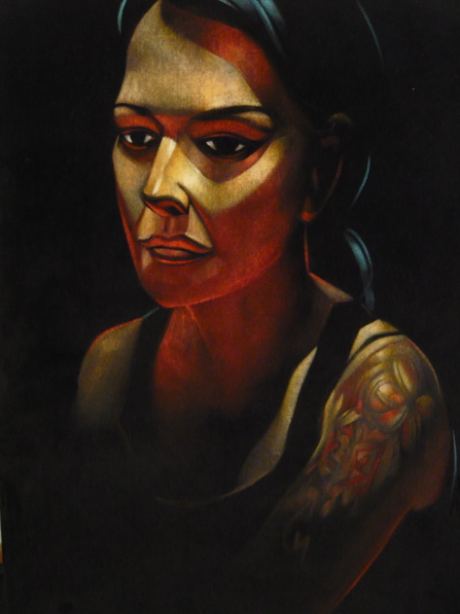

Back to black, always in style. As Joseph Park aptly observed, “You cannot take this shit too lightly. I’m psyching myself up to try it again.” Below, his gorgeous portrait of Seattle art dealer Kirsten Anderson.

Back to black, always in style. As Joseph Park aptly observed, “You cannot take this shit too lightly. I’m psyching myself up to try it again.” Below, his gorgeous portrait of Seattle art dealer Kirsten Anderson.

an ArtsJournal blog