2009 P-K Awards here, average award, $16,000. Seattle artists on the list are:

Rick Araluce, Etsuko Ichikawa, Ken Kelly and Alex Schweder. Congrats all.

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

2009 P-K Awards here, average award, $16,000. Seattle artists on the list are:

Rick Araluce, Etsuko Ichikawa, Ken Kelly and Alex Schweder. Congrats all.

If Culture Grrl’s list of stories missed by the New York Times is accurate, the NYT culture desk would be wise to give it some thought. Her complaints would have more weight if she had gone on to say what she appreciates about NYT’s arts coverage. In visual art, at least, it’s stellar. I don’t understand why so many art bloggers have a hard time coughing up a compliment for the Times.

Constant nitpicking against it gets old. Reminds me of Olive Oyl’s dad saying over and over in Popeye, “You owe me an apology!” Let me get my form letter of apology and sign a dozen in advance.

Spiders made this: (story here)

Bill Viola was temporarily Jeff Weinstein’s hero when he declined to participate in Pope Benedict XVI’s conference on spirituality and art. Good piece by Weinstein, as per usual, although it ran under the mysterious subhead, Who Would Expect a Video Artist To Be a Hero? Why not expect a video artist to be a hero? Viola no longer is, as least as defined by Weinstein, because Viola changed his mind and will attend.

Bill Viola was temporarily Jeff Weinstein’s hero when he declined to participate in Pope Benedict XVI’s conference on spirituality and art. Good piece by Weinstein, as per usual, although it ran under the mysterious subhead, Who Would Expect a Video Artist To Be a Hero? Why not expect a video artist to be a hero? Viola no longer is, as least as defined by Weinstein, because Viola changed his mind and will attend.

Instead of his original statement, issued by his dealer and quoted by Weinstein, “Bill Viola doesn’t agree with many of the policies put forth by the

Vatican and the Catholic Church and this is his reason for declining to

participate,” Viola now says the issue is so important he’ll show up, story here.

Like Weinstein, I cheered Viola’s first impulse, but the best comment came from Jen Graves:

But seriously: Church, if you want to get the attention of artists, do like you used to do–throw money at ’em. (more)

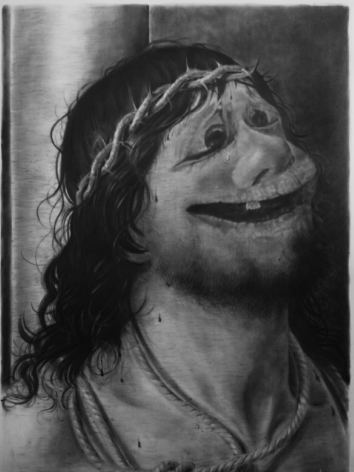

I’ll believe the Pope is serious about engaging contemporary art when he commissions Eric Yahnker. (Yahnker was recently at Ambach & Rice. My review here.)

Eva Diaz on Lisa Oppenheim’s Dead Letter Office, an altered-photo series that sounds like a terrific 9/11 memorial:

Eva Diaz on Lisa Oppenheim’s Dead Letter Office, an altered-photo series that sounds like a terrific 9/11 memorial:

Dead letter office. The phrase nags at me; it seems too direct, perhaps insensitive to use, given the context. The dead letter office is what happens to public artworks that have outlived their civic life and, due to the vicissitudes of time, taste, and politics, find themselves with no public. Their large scale makes it unlikely they’ll find another home, so they may end up stored in the basement of the World Trade Center until 2001. Then, well, we know the rest.

…Now these forever absent works exist only in photographs: the death of the dead letter office. Oppenheim’s series is, however, the birth of a gracious memorial to all that was lost. (more)

Diaz wrote no more than a long paragraph but covered everything. An image would have been nice, however.

Did Jackson Pollock sign his name all over the all-over abstraction of Mural from 1943? I’d say yes. Fascinating to see what was there all along. (Story here.)

From dogs to the deep space of an eyeball: Douglas Britt interviews Keith Carter, here. Speaking of deep space, stars eat each other, story here.

In the interests of ending on a positive note, here’s Andrew Junge with something you gotta have.

Referring to this post, no-last-name-offered Eric wrote:

Regina. I read with interest your claim that Seattle has 10 top

galleries. In what way top? Try as I might, I can come up with only

four that even marginally live up to that description: Greg Kucera,

James Harris, Howard House and Lawrimore Project.

There are more than 10 I’d call top.

The first meaning of top is that I see every show, even the rare ones I’m not looking forward to, because I respect the dealer’s record and know the opportunity exists to be surprised. These galleries are Ambach & Rice, Greg Kucera, Howard House, James Harris, Lawrimore Project, Francine Seders, Platform and Punch.

That’s eight. Top also includes galleries that are good to great within their specialties, such as Roq La Rue for Pop Surrealism, Traver for glass, G. Gibson for photography and Martin Zambito for Northwest historical.

That’s twelve. If art cooperatives can be included as galleries, then both Crawl Space and Soil make the the list. That’s fourteen.

On a different list are Seattle’s B galleries. I don’t see every show, but I check their Web sites each month. The strongest of them is Davidson Galleries. In this group, galleries offer something I find engaging once, twice or even three times a year. (Davidson is more like six times a year.) They include Foster/White, Grover/Thurston, Catherine Person, Fetherson, Friesen, Lisa Harris, Linda Hodges, Winston Wachter and Woodside/Braseth.

There are two galleries that are also bars that show signs of turning out to be better than B-list. They are Grey and Vermillion. Joe Bar is not as good but still better than most on the B list.

There are galleries that are too new to judge but show great promise, chiefly, Ohge Ltd, adjacent to Lawrimore Project, and Cario Cairo.

If I absolutely had to come up with a top ten list, I’d add Crawl Space and Ohge Ltd to the first category and call it a day.

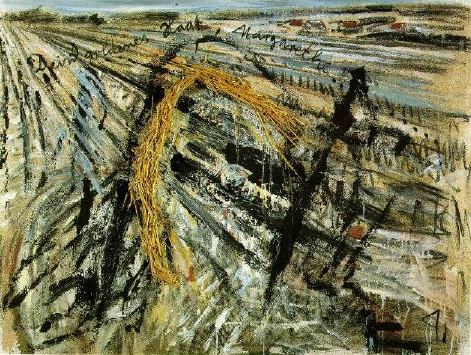

Kiefer, Your Golden Hair, Margarete (Dein goldenes

Haar, Margarethe), 1981

Nan Goldin, Sunset Like Hair, 2003

Nan Goldin, Sunset Like Hair, 2003

Susana Raab, Hot Dorothies, 2009

Susana Raab, Hot Dorothies, 2009

Gala Bent, French Braided, 2007-2009

Gala Bent, French Braided, 2007-2009

Nayland Blake, Gorge, performance restaged in 1998.

Nayland Blake, Gorge, performance restaged in 1998.

Lauren Grossman, Behold, 2003 via Howard House

Lauren Grossman, Behold, 2003 via Howard House

Jennifer Zwick, Hanging, 2007

Jennifer Zwick, Hanging, 2007

Alice Wheeler, Self-Portrait as Wicked Witch of the West, 2002

Alice Wheeler, Self-Portrait as Wicked Witch of the West, 2002

Dapper white boys and comely white girls enjoyed themselves in the comic-strip version of college life until the late ’60s generation popped the bubble. In Frat Rats, Roger Shimomura painted the prelapsarian experience but added another icon dear to the hearts of the greatest generation: Racism.

Shimomura paints racist incidents from the racist’s point of

Shimomura paints racist incidents from the racist’s point of

view. The Asian male posing for the camera is a buck-toothed lizard. His yellow hand wraps the slender ankle of an all-American girl. Anyone looking at his paintings is seeing through the eyes of a white person who fears and loathes all others.

Not me, you might say, and you might be right. But you are the one looking.

Shimomura’s cold, flat style — a blend of Pop and Japanese

ukiyo-e — gets inside his hot subject to give it a deadpan edge.

His paintings in his exhibit titled Yellow Terror: Always a Foreigner at the Wing Luke Museum are windows to a demented world.

(Yellow Terror, 2008, acrylic/canvas, 60 x 72 inches. That’s Shimomura low in the center, making slant eyes.)

Every year the MacArthur Awards embrace the individual efforts of the

country’s artists, scientists, economists and (still employed)

reporters, reminding them that whether they are in or out of the

mainstream, their excellence counts.

This year, three of the seven in the arts are visual: Mark Bradford for collage painting, Rackstraw Downes for oil painting, Camille Utterback for video.

That leaves Heather McHugh, who is a poet; Deborah Eisenberg, a short story writer; Edwidge Danticat, a novelist; and James Longley, a documentary filmmaker.

I can’t speak to awards in anything but the arts, aside from saying

that mathematician L. Mahadevan enthralled me in his interview on NPR. In the arts, however, there are no dancers, choreographers, musicians; nobody working in the recently reinvigorated public art realm.

With the exception of McHugh, there’s nobody fusing forms to produce hyrid realities, and nobody whose efforts shape the moment and suggest the future. McHugh is the Attila the Hun of poetry. She sweeps down from the hills to claim all lowlands for verse. She claims all speech, turning it into a wisecracking sound stream, both precise and wide open.

Aside from her, the list has an elegaic feel. Eisenberg’s stories are exquisite minuets. Danticat is a 21-century Proust, animating her past. Longley’s films have a magisterial detachment, as if they cover not the Iraq War but the Trojan one. I love Downes’ paintings. If I were on the committee, I might easily pick him, but again, his work looks backward.

The two remaining artists are mistakes. Bradford might still make a major contribution, but he’s not there yet. What does he offer that Kurt Schwitters didn’t long ago? Utterback has larger problems. Her work is labored and gee-whiz, look-at-my-special-effects.

From her Web site, describing Come to Pieces from 2001:

Imagine seeing yourself from four different angles at once.

Picasso imagined that in 1907, far more powerfully. If I want to see myself from different angles in real time, I try on clothes in a dressing room.

A few exhibits I almost missed, and one I still have…

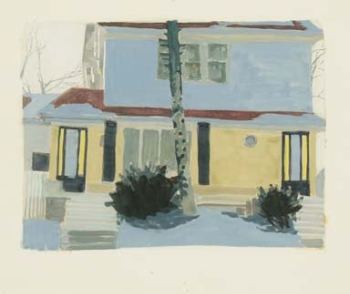

Michael Howard at Francine Seders through Sunday. His acrylics are paintings under construction of houses under construction. Earlier versions were more elusive in subject matter, featuring houses that could go either way, being built or torn down. Present ones look abandoned. Nobody’s working on them, but there they are.

His watercolors are very Fairfield Porter but with a twist or two, such as the tree in the image below, which seems to be suffering from some tree plague instead of serving as surface for melting snow. The partially melted snow on tree and house has gone on strike and refuses to melt further. It will be there forever, as long as the image adheres to the paper.

Upstairs, Gail Grinnell shares a gallery with her son, Samuel Wildman. He made a giant red skull in wax and plaster that had to be cracked in half to get out of the studio. On the way upstairs at Seders, it broke again. Francine thought he’d have to repair it and wondered if he had time, but he liked the pieces and left them on the floor, where they now resemble a broken heart. A shot of the whole head below, which did not turn out to be the finished product.

Upstairs, Gail Grinnell shares a gallery with her son, Samuel Wildman. He made a giant red skull in wax and plaster that had to be cracked in half to get out of the studio. On the way upstairs at Seders, it broke again. Francine thought he’d have to repair it and wondered if he had time, but he liked the pieces and left them on the floor, where they now resemble a broken heart. A shot of the whole head below, which did not turn out to be the finished product.

Turns them into parched plains, with lettering running in dry gullies.

Alison Keogh is at Francine Seders Gallery through Sept. 27.

Alison Keogh is at Francine Seders Gallery through Sept. 27.

Cosmetic change has a bad rap, but not Tirana, Albania, a blighted city revived by the application of squares of color to crumbling buildings, celebrated by Anri Sala in “Dammi i Colori” (Give Me the Colors), from 2003.

Two public projects tapping the same vein are among the most successful in Seattle’s recent history: Dan Corson‘s Wave Rave Cave under a freeway off-ramp on Alaskan Way in Belltown, and Sheila Klein‘s Roosevennavelt: Columnseum, 10 acres of wasteland under the 1-5 freeway on Roosevelt near 65th St.

Two public projects tapping the same vein are among the most successful in Seattle’s recent history: Dan Corson‘s Wave Rave Cave under a freeway off-ramp on Alaskan Way in Belltown, and Sheila Klein‘s Roosevennavelt: Columnseum, 10 acres of wasteland under the 1-5 freeway on Roosevelt near 65th St.

Corson’s site is a strip between two chain-link fences. To overcome the impact of those barriers, he created wave-like mounds in concrete and covered them in gravel. During the day, their oddity is charming. They look as if a construction crew longing for the sea took license with company equipment during the lunch hour.

At night, those waves become psychedelic stalagmites.

At night, those waves become psychedelic stalagmites.

Klein treated freeway pillars as dresser’s dummies. Vertical lines are so slimming.

Klein treated freeway pillars as dresser’s dummies. Vertical lines are so slimming.

an ArtsJournal blog