Looked for a job lately? (via)

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

Looked for a job lately? (via)

Say your life broke down. The last good kiss

you had was years ago. Richard Hugo

Buddy Bunting, Victorville, California, 2009, ink on paper.

Detail:

Detail:

At Soil through Sept. 26

Bunting:

Late one night in the summer of 2005, while driving south on U.S. route

395 towards Los Angeles, I passed through the town of Victorville,

California. At the time I was unaware of the new Federal Prison there,

but approaching the town from the desert its presence was made clear by

the distinctive illumination of prison lights visible on the edge of

town.

Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, 1912

Scott Reeder, Cops Ascending Staircase, 2009

Dan Webb, Heads Up! (detail), 2005

Heads Up!

Heads Up!

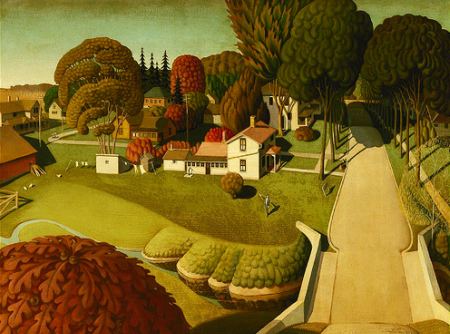

(Below, Grant Wood, The Birthplace of Herbert Hoover, 1931, painted a year after American Gothic.)

Thanks to the Depression, Hoover was one of the most despised men in

America, but not by an America First, bread-basket regionalist like

Wood.

In

In

the end, his celebrations of his region transcended it. He might have

been a narrow man, but as a painter, the fine-lined, lyrical urbanity

of his landscapes remains a marvel. With a paint brush in his hand,

Wood had rhythm, and Wood had swing.

Within the utter control of Wood’s manicured grounds is an antic

spirit. If Betty Boop came out the back door of his happy Hooverville

to sing on the lawn and all the trees and shrubs swayed in chorus, who

would be surprised?

Artists honor the past by improvising on it in the present. Currently at Punch Gallery are Nathan DiPietro‘s small paintings in a series titled, Neo-Suburban Palouse, an exploration of Wood’s duality painted in the round on egg tempera on panel.

The

The

fantasy maple oak on Wood’s lower left has an echo in the fantasy maple on

DePietro’s DiPietro’s lower right, a painting titled as a tip off, After the Birthplace of Herbert.

Wood’s trees have a lollipop sensibility, but DiPietro’s are space

ships colored like Necco Wafers. They only pretend to toe the line in

rural red America.

(DiPietro detail) “Give

“Give

me liberty or give me death,” said Patrick Henry. Why is it that the

right who treat Henry as a saint seem to long for surveillance? Its

members can’t wait to knuckle under, to be vulnerable to wiretap

without warrant, told what they can read, whom they can (and can’t)

sleep with and when they have to have children.

From the point

of view of its proponents, what would a society regulated by the right

look like? Wild nature would be gone, but tidy plots and man-made lakes

would shine in the sun.

(Above, DiPietro’s Lakeside. )

(Above, DiPietro’s Lakeside. )

Another Wood link: Wood loved the pre-Renaissance Italian painters, especially Duccio,

who modeled his mountains on rocks in his studio and populated his

ground with strange little trees. There’s more of the Duccio feeling in

DiPietro than in Wood. It’s only a matter of time before DiPietro

paints Jesus in the Suburbs. Through Sept 26.

Ben Hirschkoff, the sky, not falling:

Tonya Solley Thornton, a disco waterfall:

Tonya Solley Thornton, a disco waterfall:

Jesse Edwards, waterfall during an explosion or just after:

Jesse Edwards, waterfall during an explosion or just after:

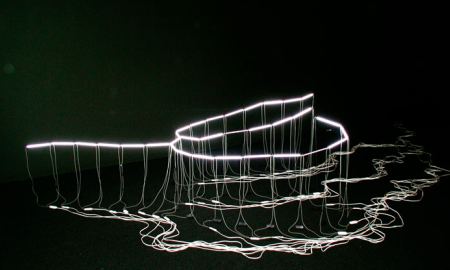

Claude Zervas, a river of light (“Nooksack”):

Claude Zervas, a river of light (“Nooksack”):

Joy Garnett, a river of flesh, flesh being, as de Kooning once said, the reason oil paint was invented:

Joy Garnett, a river of flesh, flesh being, as de Kooning once said, the reason oil paint was invented:

SuttonBeresCuller, a pond of goldfish (no goldfish were harmed in the making of this pond):

SuttonBeresCuller, a pond of goldfish (no goldfish were harmed in the making of this pond):

Mike Simi, a movable mountain of beef stew (custom fabricated robotics and software program) …

Mike Simi, a movable mountain of beef stew (custom fabricated robotics and software program) …

as a self-portrait. (I’d know those blue eyes anywhere.)

as a self-portrait. (I’d know those blue eyes anywhere.)

Gretchen Bennett, the spread of nature though stickers:

Gretchen Bennett, the spread of nature though stickers:

Created from drawings of hybridized landscapes from the Pacific Northwest, these stickers have been placed in Brooklyn, supplanting cement and brick with scenes of propane tanks draped by coniferous trees. In turn, images from the East Coast, such as junk yard dogs, are brought back to the Seattle-Portland area in the form of stickers, ultimately collapsing the space between the landscapes of the two coasts. The stickers can be downloaded and printed, spreading mongrel bits of landscape far and wide, continuing their viral migration to cereal box state lampposts, Canadian kiosks and Prague stucco.

Elizabeth Sandvig, Rabbits at Sea, because we’re so mean to them on land:

Vaughn Bell, Your own Mt. Rainier. You can take it for a walk.

Vaughn Bell, Your own Mt. Rainier. You can take it for a walk.

And speaking of mountains, Alex Schweder:

And speaking of mountains, Alex Schweder:

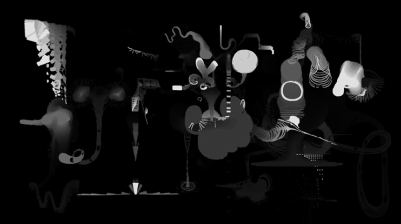

In 2005, Taeshi Murata’s single screen,

4-minute video projection, Monster Movie, left other fur-based miasmic abstractions hiding in their hovels. It’s a straight shot of

adrenalin, full color pulsing around a shimmering beast that

shakes its matted fur to the beat. This video is what Psychedelia

could have been but didn’t rise to, colors like rockets coming at you

and shapes emerging from and sliding back into moving seas of radiant

mud.

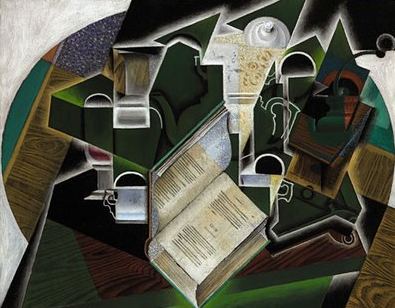

Is Murata moving through the history of art? Homestead Grays (below, 2008 still from video via) is pixilated Cubism.

Juan Gris, Book, Pipe and Glasses, 1915

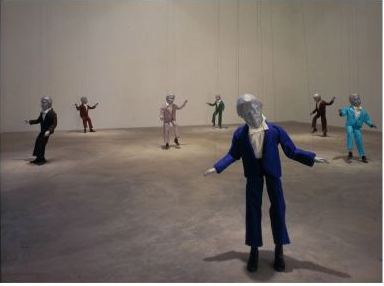

If you haven’t been down to the Frye to see The Puppet Show, it ends Sept. 13. To reassure anybody who is reasonably averse to the whimsical qualities of the genre, those aren’t the puppets in question.

Take, for instance,

Dennis Oppenheim’s Theme for a Major Hit (1974).

To

answer his own question – how to make performance art without being

there? – he created a cadre of his own mini-me’s. Dressed in hip suits,

they assume various unruffled positions till a timer goes off and they

dance.Puppets are rarely cool. They’re fall guys who are beat

on the head but rise again, bits of their stuffing clinging to the cudgel. Oppenheim’s make Andre Benjamin look awkward. They’re light on their feet, with a heavy-metal gleam in their gun-gray eyes. (more here)

Free admission.

Free admission.

When Roy McMakin was in his late teens, he fell into a depression. His

mother packed him into her car and drove not to a doctor but to antique stores. Steering him down the isles, she held up various objects and

said, “Do you like this one?”

The consolation of things. McMakin

and Jeffry Mitchell became friends 15 years ago over their mutual love

of furniture, found objects, the shiny new and the well-worn, the turn

of a phrase, art history. Both are devotees of fluid conjunctions and make work in their overlaps.

Earlier this year, they went shopping in

Centralia (droopy lumber town rich in castoffs) and purchased 30

objects which they winnowed down to 12. Each created an object in

response to the found one, all of which became an exhibit at Pulliam Gallery

in Portland, titled, by exchanging the letters of their first names, Joy and Reffry.

The show is beautifully but not literally hung. The audience is free to group found object and responses as it chooses, turning observers into collaborators. Each set of three assembled by collector is for sale for $3,600, $1,200 each to Mitchell, McMakin and the gallery.

Below, three sets assembled by me, with an extra, eight-legged found object.

1. The wisk whisk broom looks like woven hair with a top knot covered in gel, a bottom corner dipped in ashes.

McMakin made it (relatively) new again, a new broom sweeping clean.

McMakin made it (relatively) new again, a new broom sweeping clean.

Mitchell’s ceramic pair of guys who beam with fresh confidence is titled, The handsomest men in the world.

Mitchell’s ceramic pair of guys who beam with fresh confidence is titled, The handsomest men in the world.

2. This happy ghost bank has seen better days. Although not evident in the photo, someone cracked open its base to get its undoubtedly meager store of cash.

2. This happy ghost bank has seen better days. Although not evident in the photo, someone cracked open its base to get its undoubtedly meager store of cash.

Mitchell’s Ghost is a thin wash of white that rests on its own eyeballs.

Mitchell’s Ghost is a thin wash of white that rests on its own eyeballs.

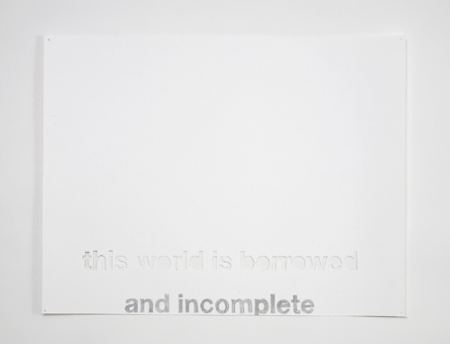

McMakin conceived of a ghost as a loss. The words in cut out and pencil lettering, are, “This world is borrowed and incomplete,” from the lyrics of a Tift Merritt song.

McMakin conceived of a ghost as a loss. The words in cut out and pencil lettering, are, “This world is borrowed and incomplete,” from the lyrics of a Tift Merritt song.

3. Tea pot as air freshner, once the scent is gone, and inset with a mirror.

3. Tea pot as air freshner, once the scent is gone, and inset with a mirror.

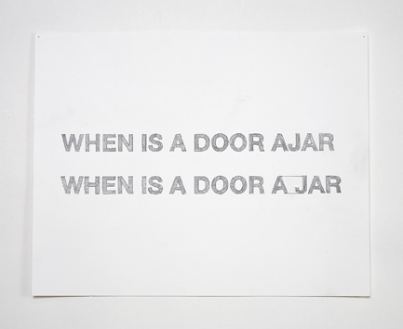

Mitchell turned the mirror into an absence, the open mouth of a jar.

Mitchell turned the mirror into an absence, the open mouth of a jar.

Classic McMakin word play:

Classic McMakin word play:

One more image, which I believe is the real model for Mitchell’s Handsomest Men in the World. Anyone at all familiar with McMakin’s furniture will marvel that he found these chairs in a junk shop. It’s his work on the shabby cheap.

John Baldessari once observed that he shared large chunks of McMakin’s vision:

John Baldessari once observed that he shared large chunks of McMakin’s vision:

A love of minimalism (while slightly poking fun at it), a Mattisean love of color, a goal of keeping others off balance, and a love of removal/absence, a quest for the paradox of simplicity and complexity. But overall, a mission to sharpen perception, it’s a significant accomplishment to get one to really see and understand a chair (and not feel self-conscious in sitting on it). I don’t think Roy has designed an ironing board yet, but I’m sure it would double as a painting. (from profile here.)

About Mitchell, I’ve written, in various places:

Hairless bears in creamy slips…generosity and

grace… conjunctions of feeling and form…. fusion of

history and fleeting moment…His great gift is an ability to turn a chaos of sources into a coherent visual stream, what 16th-century Italian Baldassare Castiglione identified in “The Courtier” as a nobleman’s highest grace, to have “sprezzatura,” a casual manner of doing a difficult thing well…

Mitchell’s casual grace masks bountiful skill. He drapes the shaggy world in silks and puts a top hat on the tawdry… He’s is a potter, but he’s also a painter and faux-fur sculptor. He works in clay, oil paint, watercolor, glass, latex, plaster, monoprints, paper, paper cutouts and wood.

There’s a two-part catalog from Publication Studio available through the gallery.

Count pillows. (Michelle de la Vega)

an ArtsJournal blog