Previous post here. Context? Paul Krugman will do.

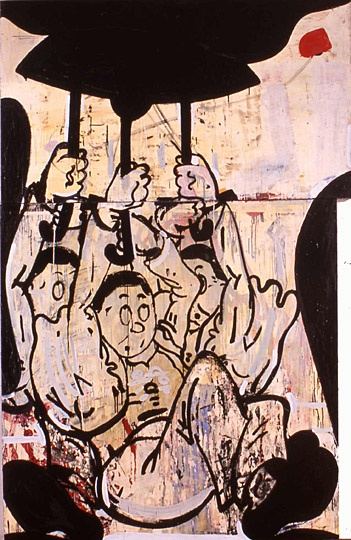

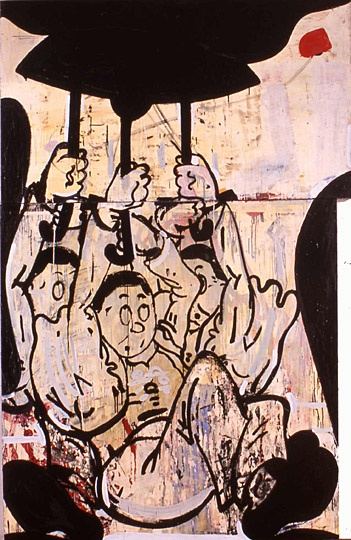

Edith Isaac-Rose (Last Supper, detail)

Edith Isaac-Rose (The Cronies)

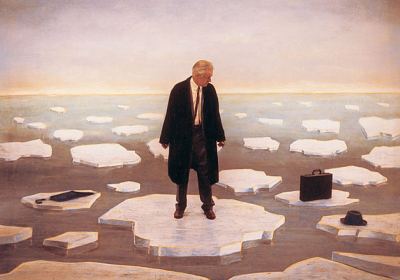

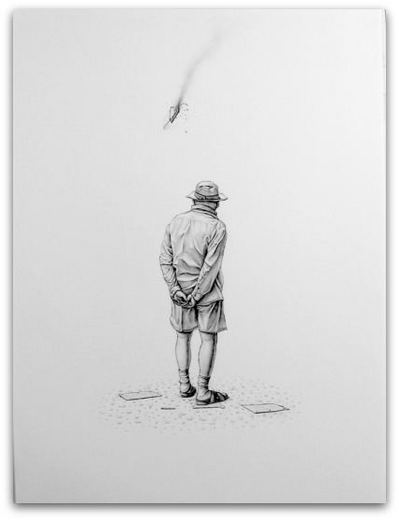

Nigel Cooke (To Work Is To Play)

Nigel Cooke (To Work Is To Play)

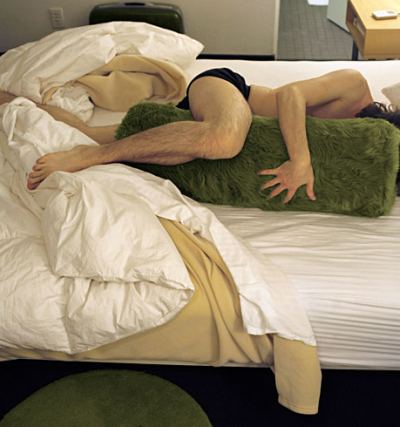

Joe Biel

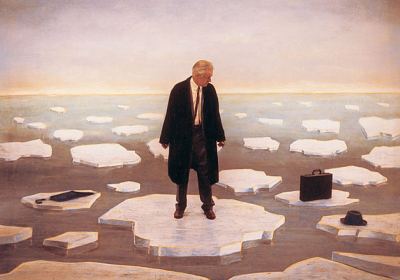

Joe Biel Karen Ganz (Float)

Karen Ganz (Float)

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

Previous post here. Context? Paul Krugman will do.

Edith Isaac-Rose (Last Supper, detail)

Edith Isaac-Rose (The Cronies)

Nigel Cooke (To Work Is To Play)

Nigel Cooke (To Work Is To Play)

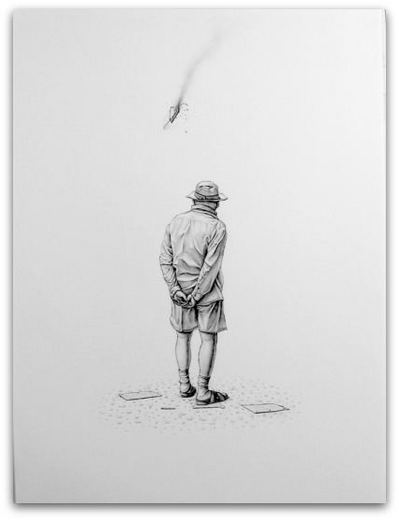

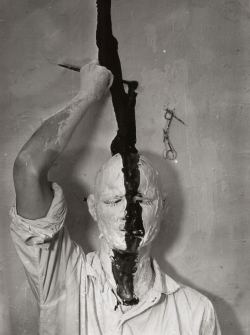

Joe Biel

Joe Biel Karen Ganz (Float)

Karen Ganz (Float)

St Helens super-volcano news here and here. Mark Morford explains it all in Your imminent apocalyptic death. It’s just around the corner. Any minute now. No really, including:

Did you hear? It’s quite possible. Right there, under Mount St. Helens up in Washington state, scientists think they can see a true, epic monster of an eruption brewing, one far more intense than the classic 1980 model, a perfect storm of gasses and pressure and molten magma, all of it the size of, well, a mountain. Times ten.

And so you think, well gosh, thank goodness I don’t live up in Washington state! I shall live far away and watch the pretty eruption, should it happen, on YouTube someday!

How cute you are.

Did you miss the noun? It’s not just a volcano. It’s a supervolcano. The eruption zone potentially spans from St. Helens over to Mount Rainier and Mount Adams … upwards of 75 miles, total. If this region blows, they say it would be the equivalent of the blast that formed Yellowstone National Park a half a million years ago. The spew would block out the sun, worldwide. It would drop the temperature of the planet. For days. Maybe longer. Does it matter? It’s the sun. The sun is sort of important.

We can’t say we weren’t warned.

Bruce Conkle, Middle Kingdom

Earth is Fucked (Blubberlamp IV)

Shaun Kardinal at Vermillion to July 5. (Group photo exhibit with Katherine Dyke, Jesse Delira, Aaron Morris and Joey Velazquez.)

Anne Karsten, Sink

Bothering President Obama is not a good idea if you’re a fly. (Much-watched video encounter here.) There’s something about the president’s calm focus followed by quick action that reminded me of this:

There are always more insects.

The history of the world, my sweet,

Is who gets eaten and who gets to eat.

Sweeney Todd, Stephen Sondheim

It had to happen. The (new) Art Baloney Blog describes itself as a collection of the “most egregious and pretentious art speak or outright bullshit we manage to unearth.” (Via C-Monster)

Writing deserving such notice certainly exists. Reading it is like shoveling smoke. But too often readers lose patience with a complicated text, assuming if they don’t understand it right away, it’s bullshit.

Art lives in its complexities. Critics digging into them can lose themselves in the effort, but isn’t that effort admirable? It’s easy to be jaunty. No, that’s hard too. To be jaunty with brains takes real effort, with the final flourish of making it look effortless. But sometimes cruise-control clarity is wrong for the art under consideration, and the writer who lets the sweat show is being most faithful to the subject.

I’d defend at least a third of Art Baloney’s examples of baloney as struggling but real.

Isn’t Colby Chamberlain’s sentence, held up to ridicule on the site, really a fine sentence marred by a typo? (From his review of Frank Magnotta at Derek Eller Gallery, artforum.com)

A display of virtuoso draftsmanship and procedural rigor, the resulting drawings offer a fluid interchange between the recognizable and the repulsive.

I think Chamberlain was going for “unrecognizable.” There are no copy editors left on earth, but that’s another problem. (File it under “no net.”) If Chamberlain meant what he wrote, recognizable, he’s got a problem with parallelism, because the repulsive is contained within the recognizable. He could have written, between the reassuring and the repulsive, I suppose, or the recognizable and the unknowable.

Onward. As a decaying bohemian who is pleased by the shout out, I’m firmly behind the following sentence by Ram Moshayedi, part of his review of Raymond Pettibon and Yoshua Okon at the Armory Center for the Arts, also from artforum.com.

Persisting as a remnant of the city’s unofficial history, the decaying bohemian icon enters into Pettibon and Okon’s project as the subcultural ideal, as the anachronistic embodiment of political nonconformity to the point of primitivism.

What’s wrong with that?

Wishing makes it so in the Museum in a Shoebox, the online-only institution that pretends to take up space in the world. (Via Bad at Sports.)

Its summer project hits me where I live. If I had ruby red slippers, I’d click them.

This July, every single billboard in the city has been taken over by the Museum. It is part of the summer advertising campaign. Usual billboard motifs have been replaced by images of clouds, the theme of the Museum’s major exhibition. Look up at the sky and see if you can find a billboard that matches the sky at this very moment!

Writing for Art Fag City, Karen Archey is persuasive on the subject of Carsten Holler‘s Vogel Pilz Mathematik at Esther Schipper in Berlin, a “high-budget, in-vogue exercise in industrial design” saved, partially, from the fatally sleek by its “off-putting, saccharinely magenta walls.”

Writing for Art Fag City, Karen Archey is persuasive on the subject of Carsten Holler‘s Vogel Pilz Mathematik at Esther Schipper in Berlin, a “high-budget, in-vogue exercise in industrial design” saved, partially, from the fatally sleek by its “off-putting, saccharinely magenta walls.”

Each of his cages had a canary in it.

Persuasive, yet I was not persuaded. Ordinarily, I am not drawn to Holler. Maybe this piece impresses me because I haven’t stood inside the gallery and instead seen only reproduced images, but a nervous blur of yellow isolated in a cluster of cages appears to animate his chilly geometries without raising their temperatures.

It’s fine to be an iceman, but an iceman voguing on art’s runway is a tough sell for those whose experience with runways is deliberately limited.

Canaries no longer exist in the wild, which isn’t enough of a reason to keep them in cages. (The same could be said of us.) In 1992 at the Henry Art Gallery, Ann Hamilton gave 200 of them the free run of the place. In the show’s early days, they kept having heart attacks. Volunteers hired to tend and feed found a couple dead on the floor each morning. After the shock of the new wore off, the death rate diminished quickly, not quickly enough to prevent animal rights activists from picketing.

I can’t remember what their signs said (Get those birds back in cages?), but the protesters at one point blocked entry to the museum with their bodies. One woman who brought her young daughter and had to step over the prone to get in reported that she was chided by them for being a bad mother.

To this day, whenever I think of canaries or see one, I think of that show, titled Accountings and curated by Chris Bruce.

To this day, whenever I think of canaries or see one, I think of that show, titled Accountings and curated by Chris Bruce.

Its power came from a metaphorical assumption of

geological time, with the Henry transformed into a blighted hulk.

Entering through smoked glass doors, viewers saw the elegant main gallery

thoroughly undone. Nearly 300,000 metal tags covered the

floor in woozy patterns. Blackened soot covered the walls, smoked by candles.

Canaries flew free. They perched on moldings, hopped around the floor, sailed through the air

and sang. With a long case in the back gallery filled with a jumble of wax

heads made from plaster molds sold in Brazilian churches as amulets

against sin and evil, Accountings functioned as a giant, moldy coat wrapping the audience in its living signs and wax symbols.

Hamilton risked sentimentality. Holler, superficiality. She overcame her limitations, and I have a feeling that Holler did too.

Bateke Proverb:

One crosses to the other side of the river only for an important reason.

In Seattle, the same applies to a lake. There are three important reasons to cross Lake Washington to get to the Eastside: the Bellevue Arts Museum, Open Satellite and the Kirkland Arts Center. The habits of a lifetime have worn a rut into the neural pathway saying, don’t go, but missing real exhibits so nearby demonstrates real inertia.

While nothing’s in the over-soon category at BAM, Seth Kinmont, Vehicle, closes tomorrow at Open Satellite and Cutism closes today at the Kirkland Arts Center.

About that title, Cutism. Being a bad speller myself, I hesitate to make a suggestion, but why not add the e? Cutism could be collage with a sharp instrument, instead of cute as an ism, Cuteism.

From Cutism:

Melissa Jones

Melissa Jones

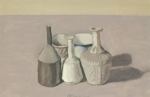

Giorgio Mordandi was not easily distracted. When fascism wreaked havoc in his

Giorgio Mordandi was not easily distracted. When fascism wreaked havoc in his

country and for decades after, he painted the same cluster of bottles, plates and tins in his studio. For

each small painting he found a rhythm, as if each were a universe that

could hum.

The artists in Target Practice: Painting Under Attack 1949-78

tend to be tone-deaf to that hum. They see what it leaves out, the

world brutally making and unmaking itself in a chaos of repression,

beauty, murder and freedom. Nor were they persuaded by the paint-driven

ambitions of the New York School, those who rode into history after

World War II as abstract expressionists. The giants of ApEx looked

inward and advanced the idea of timeless aesthetic values.

By 1949, time was up on timeless values. Curated by Michael Darling, Target Practice

at the Seattle Art Museum is a survey of the means, motives

and results of a global generation questioning the

lofty aspirations of painting as well as painting itself.

Scorched-earth

gardeners, they hoped to make way for a bloom. Darling picked not only

key work from key figures, he included a host of artists who are less familiar but hold up well in the context of the famous, such as Gunter Brus, using his body as canvas on the left, below.

Sharing space in the galleries, art from disparate sources clicks in place to generate the passion of a critical moment, dispensing with the usual thing –

Sharing space in the galleries, art from disparate sources clicks in place to generate the passion of a critical moment, dispensing with the usual thing –

scholarly dissection and imposition of hierarchy.

As a survey, it’s

wide but deep, and nobody in it comes up empty. The artists are as they

saw themselves, or, as Alan Ginsberg wrote about William Carlos

Williams, what “he tried to be among the bastards out there.”

Darling opens with Lucio Fontana‘s Concetto spaziale

from 1949. Fontana punched holes in the canvas as a means of marking

it. Aside from the novelty of his approach, his effect fits comfortably

inside the all-over realm familiar from ApEx. He tore into the canvas,

but nicely chewed what had already been chewed by others.

In the work of Shuzo Shimamoto, however, the innovative makes an appearance. In his Work (Holes)

from 1950, tears in whitewashed layers of newsprint approach their own

kind of tragic, and his scribbles in pencil on what is left of the

ground anticipate Cy Twombly.

Still, Shimamoto is firmly within ApEX, with new means to old results.

Back to Fontana, whose Concetto Spaziale from 1952 evokes Arthur Dove’s Fog Horns from 1929. Fontana’s single echoing circle stands in place of Dove’s three, but with the same reverberating lightness.

Who will look at Niki de Saint Phalle‘s ripe and juicy Tir neuf trous from 1964 (left) and not think of Joan Synder, who came later?

Who will look at Niki de Saint Phalle‘s ripe and juicy Tir neuf trous from 1964 (left) and not think of Joan Synder, who came later?

Unlike de Saint Phalle, Synder needs no guns in her studio. Her holes dripping paint are

made of paint, but both de Saint Phalle’s small canvas and Synder’s many

larger ones are not about their means of production. They are about female sexuality, and a ripeness that is past its peak.

Art comes from art, even when it doesn’t come from painting. Jasper Johns’ iconic Targets

from 1958 is rooted in early 20th-century ideas, especially Duchamp’s.

I’m rarely moved by Johns, the ice man of contemporary art, but in this

exhibit, the brilliant humor intrinsic to his endeavor is in high relief.

Fontano and to a lesser extent Alberto Burri made careers out of tearing up canvas, and Johns put the capstone on

Fontano and to a lesser extent Alberto Burri made careers out of tearing up canvas, and Johns put the capstone on

it and similar efforts in 1964, with a small pencil on paper

demonstration, Untitled (Cut, Tear, Scrap, Erase.) In vertical

columns, it does all those things, foreclosing on the option of doing

them again outside the repeat mode. How concise Johns is, and how

powerfully his work unfolds in the company of those who also tried to

make it new in the mid-20th century.

Sam Gilliam‘s Bow Form Construction, from his best period, the late 1960s and early 1970s, hangs near Lynda Benglis‘s Chi

from 1973. His painting-on-canvas sagging against the wall functions as a giant shawl, and hers as a tumorous type of

jewelry.

With his modesty, Richard Tuttle engaged the abject

with an elegance few equal, but who isn’t sick of Arman? Unlike Mordandi,

who traversed a tiny amount of ground without repeating himself,

Arman’s mounds of similar objects wear out their welcome quickly. Not the one in this show, which is a one-piece Arman rehabilitation

project: Ochre from 1967.

More than 200 tubes of paint

vomit their color, both tubes and paint squiggles trapped in clear

resin. Each squiggle is a gesture, and a gesture is, in Roland Barthes’

phrase (quoted in the catalog), “something like the surplus of an

action.”

The Japanese are a strong presence in this show,

especially Ushio Shinohara, whose performances (seen in large photos)

with paint are the equal of anything happening in Europe and America at

the time.

Shinohara:

Not content just to

use brushes, we came up with ways that would shock, aiming to evoke an

effect on those who would appreciate it.

Those who would appreciate it. He wasn’t trying to unnerve outsiders but to delight those who are capable of being delighted by him.

Johns’ Cut, Tear, Scape Erase is the cool end of Target Practice. Otto Muehl‘s Untitled

from 1963 (below, left) is one of the sensations on its hot end. Made of sand,

plaster, stockings and emulsion on sackcloth, with gaping holes bound by dark, ropey knots, its golds and blacks gleam like old jewels.

A word (or two) about the aesthetics of violence, celebrated in Target Practice. Walter Benjamin dealt with the subject in his much-celebrated 1936 essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, here.

A word (or two) about the aesthetics of violence, celebrated in Target Practice. Walter Benjamin dealt with the subject in his much-celebrated 1936 essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, here.

Benjamin wasn’t impressed by the manifestos of the Italian Futurists,

fascist to their cores. He must have thought that quoting from Futurist fascist poet Marinetti was sufficient to discredit him.

Apparently

not, but in light of this exhibit, Marinetti’s point of view is the

elephant in the gallery. Isn’t it more interesting to acknowledge it as

a kind of disgraced roots music? I like a machine-gunned canvas as much as the

next person, but what was the back story from the artists’ point of view?

Marinetti:

War

is beautiful because it enriches a flowery meadow with the fiery

orchids of machine guns…War is beautiful because it combines the

gunfire, the cannonades, the cease fire, the scents and the stench of

putrefaction into a symphony.

More on this exhibit to follow. It’s the single best survey of contemporary art ever mounted by the Seattle Art Museum.

an ArtsJournal blog