Higgins opens at Collette Blanchard June 24.

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

Below, a child greets the light in James Turrell’s Skyscape at the Henry Gallery. (Image from the Henry Gallery’s flickr pool.)

James Turrell likes to describe his grandmother telling him that the point of silence for Quakers was to “go inside and greet the light.” Nobody in Dale Chihuly’s childhood asked him to greet the light. With his brother and father dead by the time he was in his mid-teens, his mom had a bar she frequented whose exterior bled neon colors in the night rain. He remembers being happy she was having a good time.

James Turrell likes to describe his grandmother telling him that the point of silence for Quakers was to “go inside and greet the light.” Nobody in Dale Chihuly’s childhood asked him to greet the light. With his brother and father dead by the time he was in his mid-teens, his mom had a bar she frequented whose exterior bled neon colors in the night rain. He remembers being happy she was having a good time.

I once asked Henry senior curator Elizabeth Brown what she thought of a comparison between Turrell and Chilhuly. She told me she thought nothing about it, because they “have nothing in common.”

Nothing? Nothing but the bottom line. They both deal with colored light.

Turrell comes out of Southern California’s minimalist movement and Chihuly out of decorative arts, a field that modernism rejected and Chihuly helped bring into the postmodern mainstream.

Nobody mistakes Chihuly’s work for a church, unless it’s the church of whoopee.

He gives shape to excess and makes it shine. Turrell dematerializes the object, and Chihuly makes a fetish of its production. Next to Turrell’s aesthetic virtue, Chihuly’s vulgarity is startling, but at his best, he has his own kind of virtue.

On the black surface of a glass pond (Milli Fiori) flowers bloom. There are water reeds, swamp grass, irises and lilies; water snakes and coconuts, heavy orbs with bright shining wings.

Chihuly celebrates the physical, and Turrell the mental. If Chihuly’s work were a fictional character, it would be Falstaff. Turrell is Prospero.

When Prospero says, “Our revels are now ended,” he’s relieved. Revels are not his thing. Asking Falstaff to tone it down is like like asking Beyonce to join a convent.

Audiences for Turrell and Chihuly diverge. They are each other’s road not taken. What if these audiences woke one day transported to where they never wanted to be, on Turrell’s high or Chihuly’s low? Would they afterward see the world with new eyes or be freshly confirmed in what they felt all along?

Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, General Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.

– One Hundred Years of Solitude

Ice thread, previous posts, enter here.

Latest: Charles Kitchings of Ambach & Rice adds the essential Francis Alys and Francis Alys again.

Thanks, Charlie!

Mary Mattingly, from her series, Nomadographies, just closed at Robert Mann Gallery.

A lot of Mattingly’s images look like photo shoots for a fashion magazine, which is not the insult it used to be. Art worms its way into contexts that were once excluded, partly because they were once excluded. Plus, within the glamorously provocative, Mattingly has that extra element, a subtle and toned-down version of Matthew Barney. She goes for the myth but leaves pomp and circumstance to others.

A lot of Mattingly’s images look like photo shoots for a fashion magazine, which is not the insult it used to be. Art worms its way into contexts that were once excluded, partly because they were once excluded. Plus, within the glamorously provocative, Mattingly has that extra element, a subtle and toned-down version of Matthew Barney. She goes for the myth but leaves pomp and circumstance to others.

(Mattingly is a key contributor to the Waterpod Project, which opens Saturday in New York City. (More info from Artforum and the New York Times.)

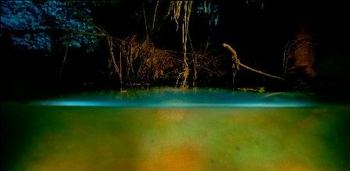

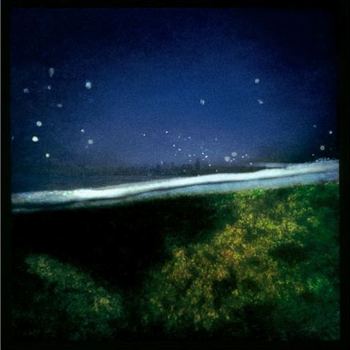

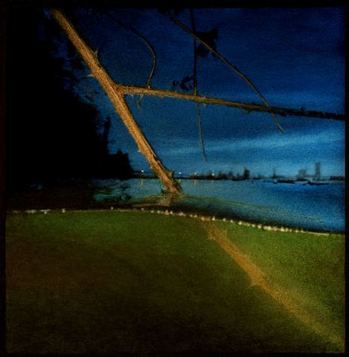

Ford Gilbreath has no relationship to the world of runway glamor. In spite of the pellucid clarity of his photographs, he’s happy to work in the mud and is best known for hand-painted gelatin silver prints shot on the Duwamish in Seattle, a river long abused by heavy industry. It has the distinction of having one of the lowest oxygen counts in the country.

Gilbreath slogged through the river’s heavy-metal murk in chest-high waders, pushing his camera in front of him in a half-submerged aquarium. With flashes attached above and below the waterline to his Hasselblad camera, he produced a simultaneous look at two worlds: air and water divided by a fluid seam or horizon line. He added density to the stark, flattened effect achieved by the camera by painting the prints in layers with transparent oils.

Gilbreath slogged through the river’s heavy-metal murk in chest-high waders, pushing his camera in front of him in a half-submerged aquarium. With flashes attached above and below the waterline to his Hasselblad camera, he produced a simultaneous look at two worlds: air and water divided by a fluid seam or horizon line. He added density to the stark, flattened effect achieved by the camera by painting the prints in layers with transparent oils.

In his stagnant shallows, scum shines and greenish-brown depths

In his stagnant shallows, scum shines and greenish-brown depths

glow. He gives the drooping clumps of dead grass that hang over unnameable, watery masses scale and force beyond their size and importance. They are monuments in ruins, as graceful in their dying fall as the ruins of Greece and Rome.

Gilbreath on the moon here. His stereoscope images in the woods (here) are the only ones I’ve seen that don’t immediately ring the William Kentridge bell.

Gilbreath on the moon here. His stereoscope images in the woods (here) are the only ones I’ve seen that don’t immediately ring the William Kentridge bell.

Batting the verbal ball back and forth is one of my favorite things! Like Woody Allen, I don’t want to play tennis with the ocean.

Below, the best political cartoonist in the country responds to my post titled, Dave Horsey derides his former (fired) PI colleagues, here. (Well played, Dave. Match set. Your favor.)

Elgin Marbles: Remember as a child when some thug who’d stolen your lunch said possession is 9/10’s of the law? It still is. Culture Grrl has the story on how the English continue to disgrace themselves, here. Don’t they want to prove there is progress in human affairs? No. They want to hold on to a tourist draw.

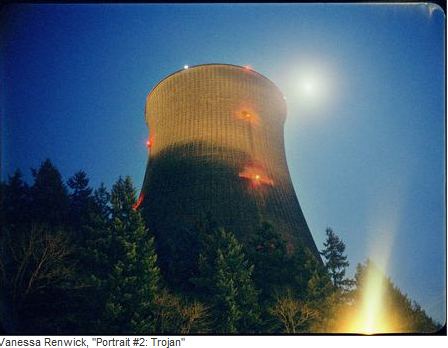

Germaine Greer: The doctor is not in, but I feel confident in saying this woman is crazy. She used to be deranged about sex, and now she’s nuts on art. She’s also a pleasure. Here she is on why nuclear cooling towers are more compelling as art than art, and better than nature. (Trees? She’s sick of them.)

If she were talking about Vanessa Renwick’s images of a cooling tower near her home town, Greer would have a point. More Renwick on her Web site: Oregon Department of Kick Ass. As many times as I’ve typed that title, I never grow tired of typing it again. To paraphrase what Mark Anthony said of Cleopatra, age cannot wither the Oregon Department of Kick Ass nor custom stain its infinite variety.

A realer reality: Blake Gopnik in the Washington Post, here.

A realer reality: Blake Gopnik in the Washington Post, here.

The real always has been important territory for artists. The difference now is that while most of the more arty, “imaginative” options are looking tired, the “new realism,” if we dare call it that, seems to be gaining ground.

It’s as likely to tweak and distort the world as to record it faithfully. It digs more deeply than ever before into what reality, and its documentation, can mean to us.

More arty options look tired? Which options are those? Such generalizations, so attractive to critics, betray an inability to be specific. Art’s specifics eat holes in the blanket of the general, and weaselly words such as “most” and “seems” cannot provide a patch.

Still, Gopnik’s essay offers a good list of artists backed by his adequate descriptions of their work. Too bad there are no links or images. Presumably, the senior art critic at the WP doesn’t have time to make what he writes minimally useful online. It’s another example of mainstream media committing suicide.

Previous on the topic: Buddy Bunting and Mike Simi.

Unlike Bunting and Simi, Steve Davis is not on the outside looking in. He’s behind bars with his teenage subjects, serving as teacher, friend and chronicler of their experience.

Sometimes, even Davis can’t get all the way in, and an institutionally-enforced failure to communicate is the subject.

Related: Chan Chao – portraits of women in a Peruvian prison, here. They’re not nearly as good, but they’re getting all the bounce. Reason? There’s work to do, so that the Northwest’s marginalized geography is not a marginalized destiny for its artists.

Below, Davis’ Intensive Management Unit, Green Hill, 2000 . Click to enlarge.

The Twining-Humber Award (via Artist Trust) recognizes women artists in Washington State who are at least 60 years old. (Previous post, One time only every year! Art world negatives become positives, here.)

More candidates? If so, email me and I’ll post them here. Or, you can skip a blog post and go directly to Artist Trust to make your admiration

official, giving your candidate a chance. Time to take that extra

step for those who’ve labored long in the field. (Go here.)

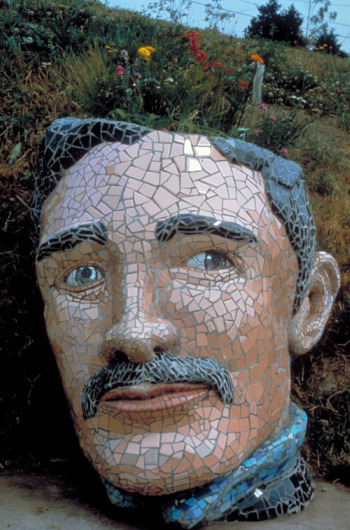

elcomancho suggests Merrily Tompkins: (No Web site. Below, Big Tesla with grass growing out of its head. More on the link. Since then, she has made jewelry, example below.)

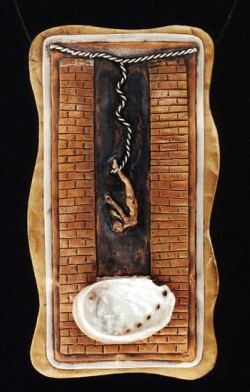

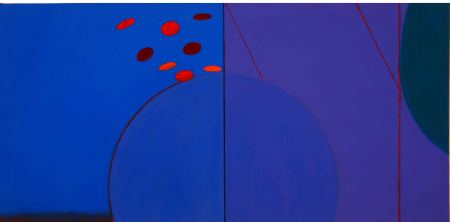

Mike Derry suggests Gillian Theobald:

Mike Derry suggests Gillian Theobald:

Several decades ago, critical opinion had begun to swing against Kurt Schwitters. In a robust age, his desire to shore up discards into a version of his life looked at best minor and at worst nostalgic.

Schwitters, Merz Picture 32A (Cherry Picture). 1921

Today he’s philosopher king. Early 21st century art has a strong interest not only in recycling ideas and materials, but in trying and failing to recycle them, leaving them in tatters.

Today he’s philosopher king. Early 21st century art has a strong interest not only in recycling ideas and materials, but in trying and failing to recycle them, leaving them in tatters.

There is a singer everyone has heard,

Loud, a mid-summer and a mid-wood bird,

Who makes the solid tree trunks sound again.

He says that leaves are old and that for flowers

Mid-summer is to spring as one to ten.

He says the early petal-fall is past

When pear and cherry bloom went down in showers

On sunny days a moment overcast;

And comes that other fall we name the fall.

He says the highway dust is over all.

The bird would cease and be as other birds

But that he knows in singing not to sing.

The question that he frames in all but words

Is what to make of a diminished thing.– Robert Frost, The Oven Bird

That bit of ordinary magic is common. It’s the story that she tells without any suggestion of a narrative, not of the glut of consumer society’s casual discards but wreckage after a fall.

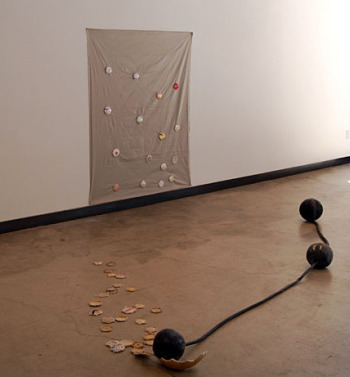

Stagger out into the light after losing everything and there are her sculptures on the floor, the flayed skin of soccer balls hung up on a wire or deflated inner tubes curled as if smoked in a fire.

She stops the cynical and seen-it-all dead in their tracks. Next to her, Anselm Kiefer seems a bit bombastic (and I love Anselm Kiefer). While his work rages, hers is absolutely quiet.

In 1957, a young Paul Taylor aspired to her kind of silence. To that end, he and his partner stood motionless on a stage for 4 minutes, in a piece called “Duet.” (The New York Times famously reviewed it with four inches of blank space.) The piece was thought ridiculous, even in time by Taylor.

What no one has done in dance, Hinrichs does with objects that become a kind of dance. They are motionless but move on.

This Saturday at noon, Hinrichs talks about her work at Howard House.

an ArtsJournal blog