Allan McCollum, Surrogate Paintings, 1979-1981

Jil Weinstock,

Green Frame Tableau,

pigmented cast rubber,

50″ x 90″ x 2″ 2008

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

Allan McCollum, Surrogate Paintings, 1979-1981

Jil Weinstock,

Green Frame Tableau,

pigmented cast rubber,

50″ x 90″ x 2″ 2008

The two poles of contemporary video art could be represented by South Africa’s William Kentridge (previous post) and Norway’s Ann Lislegaard. He’s the raw to her cooked, the coarse to her silky, the earth to her alien tread.

Since both have solo shows at the Henry (his upstairs, hers down), a little compare and contrast is inevitable, but each deserves to be seen in his/her own light.

Henry, take a bow. These shows make sense in relation to each other. The idea behind their presentation is clear – a survey from mountain top to mountain top. The third ingredient of good programming – an acknowledgment of where the Henry itself is located in the world – is missing, however. What are the NW video affinities?

At the very least, a small Gary Hill show would have been a fine thing. Seattle’s Hill stands between Kentridge and Lislegaard, leaning toward her. More accurately, she leans toward him. She matches his cool clear-sightedness, his intellectual rigor. Unlike hers, his work (like Kentridge’s) is rooted in body awareness and the tragedy of its struggles on the road to death.

Lislegaard shares Hill’s interest in language as a manifestation of

sculptural presence, but the meaning he derives is visceral, while hers

is as remote as the North Star.

(Gary Hill, still photo from Wall Piece, video. His insights along with a portion of the video here.)

Click images to enlarge.

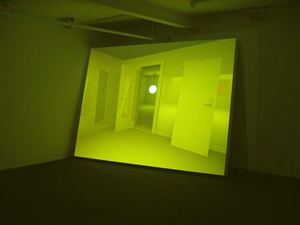

At the Henry, organized by senior curator Elizabeth Brown, are a trio of Lislegaard’s digital-animation installations inspired by science fiction. In her antiseptic world, life mutates without birth pangs from solids to liquids, spare interiors to false-front forests and texts that clarify before they blur and run.

At the Henry, organized by senior curator Elizabeth Brown, are a trio of Lislegaard’s digital-animation installations inspired by science fiction. In her antiseptic world, life mutates without birth pangs from solids to liquids, spare interiors to false-front forests and texts that clarify before they blur and run.

(Lislegaard, from Crystal World (after J.G. Ballard)

The chill from her work is real, and so is its power. Black cut against white softens to gray and turns into water. Her view of physics argues against the idea of personal volition.

The chill from her work is real, and so is its power. Black cut against white softens to gray and turns into water. Her view of physics argues against the idea of personal volition.

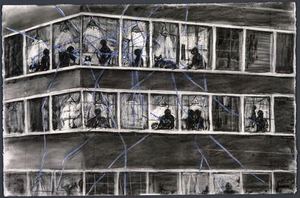

Lislegaard, Bellona (after Samuel R. Delany)

It’s a theory of everything that leaves everything out. In her

It’s a theory of everything that leaves everything out. In her

gravitational flow, we are dead stars visible on time borrowed from the

past. She’s interested in the world without the world, what impressions it leaves on the flexible coils of matter.

Note: I was thrilled to see two small exhibits honoring NW artists who died this year, Richard C. Elliott (my obit here) and Doris Totten Chase (my obit here). From no other art museum is there any indication that they lived and died here, and both mattered greatly. Bloom where you’re planted, people. You are not curating on Mars. (Thank you, Henry Gallery associate curator Sara Krajewski.)

Behold!

human beings living in an underground cave, which has a mouth open towards the light and reaching all

along the cave; here they have been from their childhood, and have their legs and necks chained so that

they cannot move, and can only see before them, being prevented by the chains from turning round their

heads. Above and behind them a fire is blazing at a distance, and between the fire and the prisoners there

is a raised way; and you will see, if you look, a low wall built along the way, like the screen which

marionette players have in front of them, over which they show the puppets. – Plato, Book Seven of the Republic, from Allegory of the Cave.

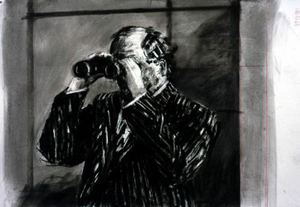

Plato waited a long time for an artist who could scratch on his wall and give his metaphor visual life. (Click images to enlarge.)

Kentridge isn’t interested in following Plato to the end of the line, aspiring to the idea of Divine Form. Leaving that hopeless ideal to minimalists, he stays in the cave with writers like Henry Miller, who wrote that “chaos is the score on which reality is written.”

Kentridge isn’t interested in following Plato to the end of the line, aspiring to the idea of Divine Form. Leaving that hopeless ideal to minimalists, he stays in the cave with writers like Henry Miller, who wrote that “chaos is the score on which reality is written.”

In the chaos of the cave, Kentridge picks up what could be a stick blackened in a fire and draws in a coarse hand. His films are one-step up from flip books. In his deft, rude style, the hard gravel of who we are finds its advocate.

Kentridge continues at the Henry Gallery through May 3, with three videos, suites of drawings and tar-like sculptures.

Kentridge continues at the Henry Gallery through May 3, with three videos, suites of drawings and tar-like sculptures.

From Rachel Shimp in the Seattle Times, reviewing Stephanie Syjuco at the James Harris Gallery:

What if you opened your cupboard one morning, and among the usual cereal boxes, a tiny slum had developed?

Right to the point with an arresting image. I have no idea who Shimp is, but she joins a team of good writers covering visual art for the Seattle Times after the ST dispensed with its staff position. I wrote about this interesting twist of fate in an earlier post titled, “Eliminate the art critic. Result? More and better art criticism.” Shimp could be the best of a promising group.

David Bonetti, writing on staff for the Post Dispatch, is seasoned and smart. There’s more to his review of Claudia Schmacke’s installations than Shimp’s review of Syjuco, but his lead baffles, because it’s not true.

Having grown up in Germany, Claudia Schmacke can’t be expected to know the Dylan Thomas poem “The Force That Through the Green Fuse Drives the Flower.”

Thomas was Welsh. Why would one European be less likely than an American to be familiar with the work of another European? Because Thomas wrote in English? Most of the Germans I know speak it well. Whenever I’m there, the fluent include taxi drivers, hotel clerks, waitresses and museum ticket takers. His lead was a moment of asleep-at-the-wheel. Late blooming reviews are unread reviews. Blow the first sentence, and the wandering eye moves on.

Responding to this post, about the value of acquiring an MFA, Seattle artist Steve Veatch observed that “there is no such thing as a self-taught artist, just as there is no such thing as the self-made man:”

Whether you go to art school or not, you will only learn by doing the work yourself and being guided by someone. “Self taught” artists can’t operate in a critical vacuum. And if you don’t go to art school, and you go to museums and galleries and turn to books and magazines for instruction and insight, you will have to ask what their academic connections are. “Self taught” is just a marketing device, as is “outsider”.

Steve. Of course there are self-taught and homemade artists, artists who never set foot inside an art museum or read an art magazine. Some didn’t go any kind of school, never mind art school, and they created all by themselves, without a community of like-minded others.

As an old man, (1) Bill Traylor started drawing on pieces of cardboard while he sat on the street. Born deaf and mute, (2) James Castle drew in spit and dirt in Idaho, using whatever paper or cardboard he could find. (3) James Hampton was a solitary janitor. After his death, his landlord happened upon his masterpiece.

Who taught them? A lot of artists in this vein say God did. I think art might be genetic to our species. There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

If guns were Delftware ceramics, warring states would be art collectors. (Charles Krafft)

Back in the world where guns fire and grenades turn their targets into pink mists of pulp, small gestures count and may be useful. (YaChin You)

Back in the world where guns fire and grenades turn their targets into pink mists of pulp, small gestures count and may be useful. (YaChin You)

Ruth Trevarrow: Chicks Dig Me and Mine, thanks to F. Lennox Campello

Rebeca Bollinger

Untitled (Beverly & Fairfax No. 1), 2006

C-print on aluminum panel, edition of 6 –

28″ x 32″

Dan Webb, Hiker. Pack up all my cares and woes.

an ArtsJournal blog