Günther Brus‘ Selbstbemalung (Self-Painting) from 1964 is in Michael Darling’s Target Practice: Painting Under Attack, 1949-78 at the Seattle Art Museum, June 25-Sept. 27.

Archives for April 2009

Coming up – Seattle Art Musem: Alexander Calder, Michelangelo

Opening Oct. 15 at SAM, two shows organized by the museum that aren’t going to travel. (Click images to enlarge.)

1. Alexander Calder: A Balancing Act, curated by Michael Darling. The idea is to trace the origins of his signature style through his initial efforts to its flowering largely through intimate objects, from 1927 to the mid-1970s.

Seattle collectors John and Mary Shirley own a hefty share of the 80 objects, many of which haven’t been publicly exhibited. Calder has recently been at the Whitney and MoMA. The concentration in Seattle will be the 1940s.

Seattle collectors John and Mary Shirley own a hefty share of the 80 objects, many of which haven’t been publicly exhibited. Calder has recently been at the Whitney and MoMA. The concentration in Seattle will be the 1940s.

2. Michelangelo Public and Private: Drawings for the Sistine Chapel and Other Treasures from the Casa Buonarroti, organized with the Buonarroti by Chiyo Ishikawa.

From the press release:

Renaissance biographer Georgio Vasari tells us that Michelangelo burned

most of his drawings and other preparatory works before his death “so

that no one should see the labors he endured and the ways he tested his

genius, and lest he should appear less than perfect.”

Grain of salt: Vasari is not facts on file. The most promising thing about this exhibit is the chance to see the artist thinking on paper – twelve drawings. If he really wanted to hide his tracks, there wouldn’t be any.

For this one exhibit, I’m going to try to break the habit of reading wall text. Maybe SAM will surprise me and skip all that oh-the-master-genius stuff, which wraps the artist in adulatory goo. Press release again:

For this one exhibit, I’m going to try to break the habit of reading wall text. Maybe SAM will surprise me and skip all that oh-the-master-genius stuff, which wraps the artist in adulatory goo. Press release again:

In addition to drawings and models that reveal Michelangelo’s process,

the exhibition includes works by Michelangelo’s contemporaries and

generations of followers and admirers. Painted and sculpted portraits

and commemorative medals celebrating his life demonstrate the “cult of

Michelangelo” that had already begun during his lifetime.

Cults intend to honor but always alienate, a point well made in a bumper sticker: Jesus, Save Me From Your Followers.

Jacob Lawrence and the question of museum admission fees

By the time Jacob Lawrence arrived in Harlem, the party was over. The flush days of Harlem’s cultural renaissance had come to an abrupt end with the 1929 stock market crash and the beginning of the Depression.

Born in 1917 in Atlantic City, N.J., to a couple who had come north in the general migration of blacks out of the South, he found little he could count on in his early years.

By the time he was 13, his father was long gone. He and his younger brother and sister had spent three years in foster care before their mother could afford to send for them. She was a domestic with an irregular income, barely able to hold her family together.

Lawrence’s mother died in 1968, after he had become a major figure in the art world. “She was proud, but she would have been much happier if I’d had a job in the civil service,” he told me. “For people of her generation, security was everything.”

Lawrence’s mother died in 1968, after he had become a major figure in the art world. “She was proud, but she would have been much happier if I’d had a job in the civil service,” he told me. “For people of her generation, security was everything.”

As a child new to the neighborhood, he was shocked by the lack of open space, the crush of humanity and the cramped verticality of the buildings. Because he neither played sports nor followed them, he wasn’t a big hit with his contemporaries. Nor was he especially drawn to school. He dropped out of high school to help his mother earn a living.

From these unpromising beginnings, he became one of the greatest figurative artists of the 20th century. When asked about what mattered in his youth, Lawrence was quick to give credit where it belongs: to Harlem’s black community. He didn’t mean only Harlem’s extraordinary grouping of painters, musicians, poets and playwrights who befriended him, but the ordinary people with whom he interacted every day.

His first Harlem break came right away. “My mother wanted me to be safe when I wasn’t at school, so she enrolled me in an arts and crafts program at Utopia House,” he said.

His first Harlem break came right away. “My mother wanted me to be safe when I wasn’t at school, so she enrolled me in an arts and crafts program at Utopia House,” he said.

On the staff was painter Charles Alston, who recognized the young man’s drawing talent. Alston provided him with materials and some technical information, but let him build his painted, cutout cardboard cities on his own.

Lawrence continued to study with Alston, who became director of the Harlem Art Workshop funded by the Works Progress Administration Mural Project for the Federal Art Project.

Alston ran an intellectual salon. Through him, Lawrence met poet Langston Hughes, painter Aaron Douglas, writers Ralph Ellison and Claude McKay. Before Lawrence was out of his teens, McCay was hailing him as a “peerless delineator of the Harlem scene.”

Another important mentor was sculptor Augusta Savage. When Lawrence dropped out of high school to earn money, taking on a series of mind-numbing menial jobs, Savage tried to get him employment as a WPA artist. The first time she took him, he was too young. The following year, she brought him back to sign up.

“She was the first person to give me the idea of being an artist as a job,” he said. “I always wanted to be an artist, but I assumed I’d have to work in laundry or something of that nature.”

The heady company he kept encouraged his intellectual interests, and he spent many hours in the Harlem library, studying the history of African Americans, research that would result in his first great cycles of narrative paintings.

He also accompanied various mentors on trips to downtown galleries and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, eventually going by himself on foot, 60 blocks south of his home territory. While still a teenager, he developed an appreciation of early Renaissance art, the murals of Jose Orozco and the paintings of Arthur Dove, John Marin and Kathe Kollwitz.

I think of Lawrence whenever museums rise their admission fees. He remembered the MET being free. He wanted to go, and the Met let him in. (Robert Frost: Home is the place where, when you have to go there,They have to take you in.)

I think of Lawrence whenever museums rise their admission fees. He remembered the MET being free. He wanted to go, and the Met let him in. (Robert Frost: Home is the place where, when you have to go there,They have to take you in.)

That’s why Tyler Green at MAN is right to disapprove of hikes at the gate (here and here) , and Judith H. Dobrzynski at Real Clear Arts is off base, here. Dobrzynski:

I argue that some may want to try variable pricing — charging people

more for various times. The Neue Galerie attempted to do this in 2006,

with the exhibition of Klimt’s “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I,” but

gave it up after public outcry about the $50 tickets. I’m sorry they

backtracked; I think they should have tried it, at least long enough to

assess its potential.

The potential? The potential damage of excluding people is far greater than potential increases to the bottom line.

Rooney O’Neil – Men are the new women

Henry Wessel – road signs, continued

Alex Schweder & Ward Shelley: The leaky body in its portable house

In the first week of their exhibit at Lawrimore Project, Alex Schweder and Ward Shelley lived in their teeter-totter house, optimistically titled Stability.

Even when otherwise engaged, they were intimately aware of each other’s weight. With a tilt and sway, each affected the other. Should they have wanted more intimate contact, they would have had to meet in the middle, like single beds braced for fusion.

Even when otherwise engaged, they were intimately aware of each other’s weight. With a tilt and sway, each affected the other. Should they have wanted more intimate contact, they would have had to meet in the middle, like single beds braced for fusion.

Maintaining their cheerfully weird fiction that they were comfortably kicking back at home, they lived like zoo animals. Naturally, visitors asked questions. Who wouldn’t want to hear what the monkey has to say? The most common query was obvious and frequent: Where do you go to the bathroom? (Check center spine for kitchen and toilet.)

Almost 40 years ago, when engagements of this sort broke new ground (among them, those of Joseph Beuys, Tehching Hsieh, David Hammons, Vito Acconci, Chris Burden, Kim Jones, Adrian Piper and Carolee Schneeman), artists tended to be more brutal with their persons. Who’d ask Kim Jones how he accomplished basic functions in his stick suit? The evidence of urine streaked the caked mud on his thighs.

There is less existential anguish in performance art today, and possibly more focused, conceptual intent. Schweder and Shelley explore the relationship between the housing and the housed.

I was out of town during the first week of Stability, but I don’t think I missed much. The piece itself is better off without the artists in it. It floats in space like a mirage. It’s the mytical room somewhere, a burrowing dream that surfaced in the air, the snail shell we long for but cannot possibly disappear into.

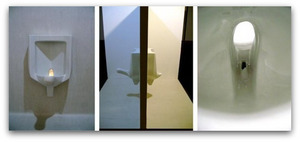

Asking Schweder where he pees makes sense, because his work is focused on body fluids. The long and honorable history of the urinal in art has never, to my knowledge, included actual urine, until now.

Below, Schweder. Plumbing Us, 2008. Virtreous china. 32 x 18 x 26 inches. Left

to right: front view of female urinal; side view showing shared wall;

detail of shared drain.

Edition of 3. The floor model is definitely in use.

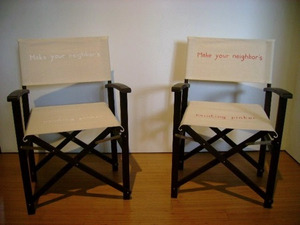

I love Schweder’s salute to Lawrence Weiner, Painting Instruction: Chair Exchange, 2009, Acrylic on canvas, Edition of 10. Each says, “Make your neighbor’s painting pinker.”

I love Schweder’s salute to Lawrence Weiner, Painting Instruction: Chair Exchange, 2009, Acrylic on canvas, Edition of 10. Each says, “Make your neighbor’s painting pinker.”

The dream of a room somewhere includes one enormous chair. Ms. Doolittle assumed the chair would hold its own under her weight, but Schewder’s version (a sofa, really) rides and fall with the movements of its occupants.

The dream of a room somewhere includes one enormous chair. Ms. Doolittle assumed the chair would hold its own under her weight, but Schewder’s version (a sofa, really) rides and fall with the movements of its occupants.

.

.

Through May 2. My review of Schweder’s A Sac of Rooms Three Times A Day here. Jen Graves here. Graves on Schweder receiving The Stranger’s 2007 Genius Award for visual art here.

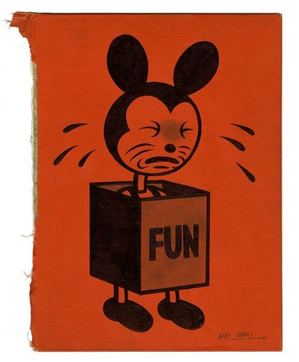

Gary Taxali – Failing the Cat in Hat test

Look at me!

Look at me!

Look at me NOW!

It’s fun to have fun

But you have to know how!

Dr. Seuss, Cat in the Hat

Taxali at Jonathan LeVine Gallery till May 2.

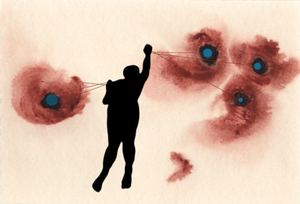

Jenny Zoe Casey – Icarus continued

Why should I travel when I’m already there? Charioteer via artist’s Web site.

Art about money – the bottom rises to the top

Following the worldwide crash, the heart has gone out of art about big money.

Following the worldwide crash, the heart has gone out of art about big money.

Once seen as the equivalent of a medical examiner performing an autopsy, For the Love of God has taken its rightful place as the corpse. With $20 million in rock candy glittering on its $100 million skull, it is more symptom than diagnosis. As such, the piece is a more powerful, less didactic work of art. A year ago, some dismissed it as a frivolous joke. Anybody laughing now? Certainly not the artist, whose chances of recouping his investment continue to dwindle.

Chris Burden’s One Ton One Kilo (100 kilos of gold) slipped between cup and lip. As he learned to his sorrow, his middleman being a Ponzi schemer, toying with the root of all evil has big bite-back potential.

Art about more common currencies continues to thrive. Too bad Cornelia Parker’s 30 Pieces of Silver isn’t on view. (Detail below) This is her moment – the betrayal inherent in consumerism finds its perfect expression in this piece. Her flattened objects may appear, like us, to be heading for the slag heap. Unlike us, however, they retain their allure.

Nothing is more common than a penny. “The lowly penny,” said Jack Daws. “People don’t bend over to pick it up.”

Nothing is more common than a penny. “The lowly penny,” said Jack Daws. “People don’t bend over to pick it up.”

They would if they realized he’d made it. Daws fabricated 10 18-karat gold pennies and used one in a coffee shop at the Los Angeles airport. Each cost roughly $100 to make; Daws’ gallery, Greg Kucera, is selling the remainder for $1,000 each. The Treasury Department Secret Service takes a dim view of fake money in circulation, but Daws figures he’s safe, as his penny is value added, not detracted.

Other artists blurring the boundary between art and money include Gary Hill and JSB JSG Boggs.

Frank Ryan – road signs, continued

Frank Ryan, Overpass, oil/canvas, 40×48, 2008 (Click to enlarge)