Good art gore post on Modern Art Notes, here. MAN’s Tyler Green went looking for intestines at the Philadelphia Art Museum and found plenty.

One of his comparisons, however, doesn’t quite make the grade – Jeff Wall’s

Dead Troops Talk (a vision after an ambush of a Red Army Patrol, near Moqor, Afghanistan, Winter 1986) with Caravaggio’s The Incredulity of St Thomas.

Dave Hickey forged the link that matters between contemporary art and Caravaggio’s Incredulity in The Invisible Dragon: Essays on Beauty from 1991, long out of print and now available in a reissue, here. Specifically, in a chapter titled, Nothing Like the Son, Hickey compared Incredulity with Robert Mapplethorpe’s photo of a man sticking his finger in his penis. (Images and text of this chapter here.)

Wall’s work is remote. That’s its signature. It’s cold to its core. In contrast, Caravaggio’s painting and Mapplethorpe’s photo are all about touch. Both are as perverse as they are seductive.

John Berger wrote about Caravaggio’s voluptuous intimacy two decades before Hickey, the electric charge of the boy Cupid’s wing resting his thigh, but Hickey found its present-day equivalent in the work of an artist not credited with it. Before Hickey, Mapplethorpe was seen as stylishly meticulous. The kink in his content didn’t change that, but Hickey did.

The pre-Hickey view of Mapplethorpe was instantly out-of-date. The book was a game-changer, plus big fun to read. Back to intestines. In art, a writhing form is a writhing form.

(Click images to enlarge.)

In Sabrina Small’s Duality, intestines are the equivalent of umbilical chords:

In Michael Spafford, they’re a fatal form of father-son bonding:

In Kris Martin, they’re present in their absence.

In Masami Teraoka, they’re octopuses.

In Karen Liebowitz, a horn.

In Claude Zervas, they’re a river.

Top 10 questions for art guards

By Ryan Molenkamp, painter and security chief at the Frye Art Museum, printed his insider top 10 list with his unfortunately unlinkable story, Basic Training for the Avant Guard, in Seattle City Arts, April edition.

10. What is the most expensive piece here?

9. I should show my art here; can I see the curator?

8. Did you ever see Night at the Museum?

7. I’ve got this painting. (Describes work vaguely, typically forgetting the artist’s name.) Can you tell me how much it is worth?

6. Why is it so hot in here?

5. Why is it so cold in here?

4. Do you get bored?

3. Why can’t I bring my coffee in?

2. Has anyone ever stolen anything?And, of course:

1. Where’s the bathroom?

Molenkamp’s Web site here.

I love Marilyn Minter

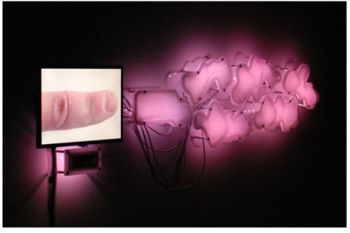

Pull my finger – Tivon Rice at 911 Media Arts

Pick a neighborhood in North America, from Newport Beach to Newark. Walk its streets at night, you’ll see the flickering colored lights of televisions talking to each other in living rooms, dens, kitchens, bedrooms and baths.

The cathode ray light that saturates most of the world didn’t exist until Philo Farnsworth invented it in 1928. Because he believed that corporations could be trusted, his career was a sad one. The honor they didn’t give him came after his death, when Nam June Paik in 1974 turned what Farnsworth had wrought into art.

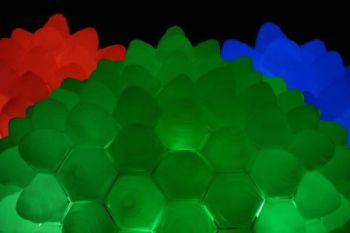

Although Paik is interested in everything about television, its shape and sound qualities, its pretensions to realism, its hallucinatory snows, blips and flickers, Seattle’s Tivon Rice is interested mainly in Farnsworth’s light.

Rice’s focus differentiates him from most of the major light artists who precede him, such as Dan Flavin (fluorescence) and James Turrell (fictionalized ethereal).

From the specific, Rice moves from the spectacular and down to the humbly interactive – tube as church and tube as intimate companion.

Pink Noise: From a finger (2008) is part of his current exhibit at 911 Media Arts Center. Rub the fleshy screen under the single digit and another will appear to do what you’re doing, from gentle massage to nervous scratch.

Through Tuesday at 911. All Rice images from Lawrimore Project. More images here.

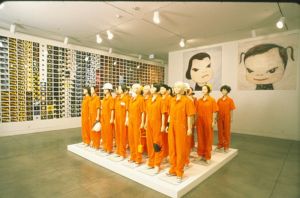

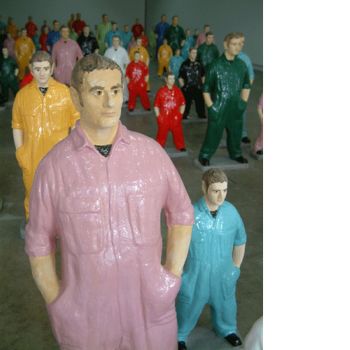

It’s raining men

Could this be the reason?

Or, more recently, this?

Whatever the stimulus package, the harvest is bountiful.

Gregor Kregar is into maintenance men.

Kerry Skarbakka tries (and fails) to defy gravity.

Hugo Ludena celebrates gay marriage in a community setting..

Mark Newport represents sold craft values. With boyhood heroes gone, he continues to knit their empty suits.

Artists who are punching bags – the hits keep coming

Julian Schnabel is one of those artists whom critics feel obligated to disdain personally. The list changes, but once artists are on it, they’ll be pricked by kicks for some time to come.

Even sanest man in art criticism – Richard Lacayo – goes mildly nutty at the mention of Schnabel’s name. Here’s Lacayo’s drive-by Schnabel hit in a discussion of Guest of Cindy Sherman by Paul H-O:

Paul comes off as a somewhat goofy but implacable guy who has a way of

getting his foot in the door and a sense of humor about himself. He’s

not afraid to show us footage of artworld blowhard Julian Schnabel —

who (no surprise) does not have a sense of humor about himself —

telling Paul that his tv show is “a sort of masturbatory exercise in

stupidity.” (Careful Julian, that’s a pretty good description of your

entire career as a painter.)

Really? His entire career?

Another must-kick artist is Dale Chihuly. He could make mountains dance, and critics would turn away in disgust. The most recent addition to the critical no-fly zone is Shepard Fairey. Damion Hayes of the street art blog To Fear It Is To Know It is obsessed with disrespecting Fairey. How bad is it? Hayes backs AP over Fairey. That’s a disgrace. Today, again. (A rational view of the case here.)

Artists do not poison waterways, start wars or send the economy into free fall. Rigorous criticism is essential, but personal insults degrade the critic who tosses them off.

I started reading Thomas Albright in the SF Chronicle in college. He later wrote a book about Bay Area art. It’s good but not great. Albright was master of the 10-to-15-inch review in a newspaper. In that small space, he did it all: close attention to the work in question and a sweeping sense of context paired with decisive judgment, all in his confident, smart, no bullshit style.

He died in his late 40s in 1984. At his funeral, someone said that Albright’s attacks were formidable but never personal. In his reviews, Albright called no one names, not even the SF art dealers who once bought space on a billboard to say, “Fire Tom Albright.” I believe they included an exclamation point.

Desperate characters in glue

Jason Teraoka’s aging women have the predatory weight of Jose Clemente Orozco’s, especially the upside-down blonde at the bottom of the frame in a mural in the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City.

Like Orozco, Teraoka knows how to take the air out of a room. He knows how to paint glamor after it’s gone and everybody’s time is borrowed.

His women can eat you whole; his men have nothing to say and nothing to say it with. Teraoka grew up in Hawaii watching movies interrupted by commercials on late night TV.

He paints with acrylics in wet glue:

A few years ago, I became really frustrated with this painting I was working on. So I took a bottle of glue, squirted it all over, and applied more paint on top of that. I liked what it was doing, so I kept developing this method. The wet glue absorbs the acrylic paints in a certain way, so I feel like I can get a nice skin quality. I guess it’s a psychological thing too – I can really ‘feel’ the skin texture as I’m painting. As it starts to dry, it repels. That’s how I get the washes in the background: I get this foamy mix, and as I paint it over it separates, creating these interesting effects.

-from Toyoko Art Beat, full interview here.

His background is in graphic novels. If he were what Pop Surrealism were about, I’d be all over it. Instead, too often, it’s illustrative fantasy, skillfully drawn.

Teraoka is at James Harris through Saturday.

Earth to Seattle arts writers: Hello? Anybody home?

EMP hiring Christina Orr-Cahall as its next director did not go unnoticed by Seattle press: The Seattle Times published an interview earlier in the week (here), and the online-only Seattle PI managed a brief note, as did the Stranger.

Today, however, Tyler Green pointed out that Orr-Cahall was director of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in 1989 and canceled the Robert Mapplethorpe show in response to outrage from Congress, led by Jesse Helms.

It was absolutely the wrong thing to do. She resigned in response to the chaos caused by her decision. (New York Times story here.) As Green noted,

The Corcoran — and in some ways the art world — still hasn’t recovered.

Orr-Cahall appears to have been a big success as director of the Norton Museum of Art for the last 19 years. (Story here.) Surely her life’s work cannot be defined by one false move.

But nobody in Seattle appears to have asked her about it. The Seattle Times’ reporter quoted her saying she was interested in the “whole visionary side” of museums and wanted to – wait for it – “push boundaries.”

“I knew I remembered something attached to her name,” wrote Jen Graves, acknowledging Green’s post. Me too. I glanced at the PI story and thought, hmmm. Where have I heard that name before? Neither of us sees EMP as our particular concern. We don’t cover it. Isn’t that somebody else’s job? Somebody, anybody?

The mark of tiny town journalism is, when something worth digging into happens, outsiders do it or it doesn’t get done.

“Dearly, Madly” – romance as the end of the road

Passionate love is Temporary

Insanity the Chinese

say that day

I walked nine miles in a bowl

the hill makes coming round

and round avoiding

the road in

sane I realized a whole

week later….

– Olga Broumas, from Landscape with Loaves and Figure

At Howard House, the title of the exhibit Dearly, Madly comes from a pathetically excessive sentiment expressed in Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo:

I love her dearly, madly; I love her so much that I would shed all my blood to save her one tear.

As soon as it’s said, the loved one is looking for the door. Curated by artist Robert Yoder, Dearly Madly explores the spirit of doomed pursuit. The nature of the pursuit insures its failure and seals desire into an endless loop,having nowhere else to go.

Michael Dee‘s Heartsmelt (The Panopticon) is a Jeff Koons’ on the skids. Trailing its own battered props, this party is dead and doesn’t know it.

Shaun Kardinal‘s Repose is in love with its own melancholy.

In gorgeous video performances on tiny screens, Julia Oldham imitates the mating rituals of insects. She memorized their antics and can repeat them perfectly.

If Elizabeth Peyton and Karen Kilimnik did not exist, I doubt Alika Cooper would be able to invent them. She hitched her wagon to their stars, and yet hovering inside her paintings is a distinct form struggling to get out.

I’m not sure what Haim Steinbach is doing in this show. A self-possessed member of the Cool School, Steinbach has never demonstrated a flair for or interest in vulnerability. He’s the Giorgio Morandi of consumer goods, and his shelf life goes on forever.

Against time – the conservation of art

NYT art critic John Russell once called an oil painting a “vegetable construct that changes in time.” Conservation steps in to manage change, whether it evolved slowly or happened in a second.

A case of the latter: Jeff Koons’ St. John the Baptist probably cracked its arm during a short ride through Seattle from Artech storage to the Bagley and Virginia Wright Exhibition Space in 2004.

Produced in an edition of three with an artist’s proof, Saint John is from the 1988 Banality series of large-scale, ceramic sculptures.

Michael Jackson and Bubbles from the same series is the largest porcelain sculpture ever made. Saint John is a close second, at 56 inches high, 29 inches wide and 17 inches deep.

Story about the conservation efforts that left John whole but with a scar here.

Thursday night at Cornish College of the Arts is a panel discussion with the overblown title, Eros-Bios-Thanatos: Conundrums in Conservation of Contemporary Art, at 1000 Lenora Street, 7:30-9 p.m., 7th floor.

The panelists are worth hearing: Mitchell Hearns Bishop from the Getty Conservation Institute & curator, Los Angeles County Arboretum;

Nicholas Dorman, chief conservator, Seattle Art Museum;

Claire Gerhard, independent conservator, now in Seattle recently working at the Whitney, MoMa & Mozambique, and moderator Elizabeth Darrow.