Sorry for my delay in blogging. Completing a large project or returning from an engrossing adventure always leads to a temporary depression. Suddenly everything is so calm without the adrenalin. The spirit drags and the imagination dissolves. This happens at least a twice a year for decades and I still respond the same. I learn nothing.

The trip to Turkey will be very influential to my thinking for two reasons.

1.) Turkey is a moving time machine. It is an example of the future, not the past. Remnants of time and people protrude into the contemporary space of Istanbul and the Aegean. A few hours of accidental strolling take you through Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Islamic and International spaces. With a little effort the Persians, the Lycians, The Hittites, Assyrians, the Apostles of Jesus and the Crusaders. Around another corner starts the collaboration with Europe in 19th Century and 20th century architecture, design and art. If your tired, grab the sleek tram or subway back across the same history. I think Istanbul offers a fresh way into globalism.

2. The book “My Name is Red” by Orhan Pamuk. Through the detective story, Pamuk ruminates of the value of miniature painting during the challenge of Italian realism of the 16th century. I will be bringing the book forward in little pieces as I question my understanding of cultural expression verses individual expression. If relevant, I will include a quote in my various entries. Today for Richard Wilson, I quote a master miniaturist: “Painting brings to life what the mind sees, as a feast for the eyes.”

In Liverpool, England, sculptor Richard Wilson has created a new temporary public artwork called “Turning the Place Over.” On a building to be demolished, Wilson has caused an 8-meter section of exterior wall to rotate in and out of the façade. The geometry of the rotation is complex and therefore the video is the only way for the virtual traveler to know a little of the work.

Video by Nudelita on YouTube

“Painting brings to life what the mind sees, as a feast for the eyes.” The work is definitely a meal, but I don’t think a feast. No pedestrian could resist a viewing of the breaking from and re-melding with the building surface. The twisting of the cutout in the plane of the building does not quite seems possible. But just public notice (a success in some ways) does not equal public art success.

What does Wilson’s mind see? Pamuk’s miniaturist is not interested in Wilson’s personal mental observation but the common mind that has found expression through centuries of art. Art shapes what the mind sees.

Below is a not-so-arbitrary selection a series of art images that shape the common attributes of my mind regarding broken holes or the moving plates in buildings. Many more are possible such as a slow motion version of missile attack that is repeating endlessly on every television channel or radar stations or cartoon impossibilities or many architects that design holes in buildings and roofs.

At least Americans have been watching this size tilting and rotating plate at county fairgrounds during most of the 20th century. Wilson selects a size that has been experienced by most observers. The observer “feels” the tilt.

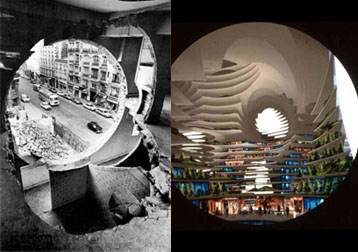

Gordon Matta-Clark cut an invisible cone into the soon-to-be-demolished Parisian building in 1975. Urban art can be made by removal, not addition.

Vito Acconci’s World Trade Center site tower constructs Matta-Clark’s destructive removal as a positive, not a negative. Carving out is a part of building up.

In Munich “Courtyard in the Wind”, Acconci shifts the earth in a fashion like Wilson’s façade in that the circular motion breaks from and then returns to design of plane.

The human tolerance for this notion of false ground – moved and placed anywhere – is highlighted during the 2005 Federer and Agassi tennis game on the heliport at the Burj Al Arab Hotel in Dubai design by Aktins Global.

So what is in the common mind of this writer? Or perhaps a better question for the moment, what is seen in the mind’s eye that is being repeated. The mind’s eye sees all human creation as insubstantial and that substantiality is a perceptual trick of our most substantial thing: architecture. The circle illustrates the insubstantial with its potential for motion and its lack of solid connection to other parts.

So we have a “history” that is not known by anyone passing on the street in Liverpool. Yet the British walkers might know that anything unusual and not seen before might be the work of an artist or a promoter. No words, then most likely art

Public Art, Public Space

Great linking of images and ideas! Thank you for sharing your thoughts, travels, readings, and research in a field where dialogue and discussion are much needed.