On January 29, 2007, Marvin Finn died at the age of 89 in Louisville, Kentucky. I have never heard of Finn before. A notice came to me via Google’s daily alert. His obituary included one “public art” project made during his 86th year.

In the Courier-Journal, Louisville Mayor Jerry Abramson praised Finn’s legacy, calling him “one of Louisville’s greatest folk artists.”

I love this statement. Not America’s, not Kentucky’s, not African-American, but Louisville’s. In many ways, our art and design bureaucracies have turned away from local pride to broader comparisons.

The “CONTINUED READING” contains the details on Finn and the project, but the mandatory front-loaded Blog concern is that local talent that has been dismissed by the nationalism of public art administration. How many times have I heard that the local artists don’t have the experience? The assumption is that the artists can’t achieve success, but the truth is that the arts leadership cannot achieve success.

Except in situations when a jurisdiction needs some strange particular skill, local artists are always capable of adorning public space and structures. It is just that the administrators and arts supporters want to be judged by national standards. They institutionalize those objectives through required methods to deliver new public art. Skills in navigating design and construction administration and skills in responding to community needs have become prerequisites.

As the Queensland (Australia) Art Built-In Programs have proven, these attributes can be achieved by other professionals assisting the artists. But frequently these required skills permit the administration to comfortably ignore local talent and to satisfy an objective of national or international participation.

As 2006 protests in Kansas City and elsewhere have shown, the local artists are forced into a position of asking for training to come up to national standards. The artists should require that the programs be re-conceptualized for the talents of local artists with exceptions granted for projects where outside artists seem like a good idea.

Here is where Marvin Finn is so important. The citizens of Louisville reconceived both their method of selecting public artworks and their method of fabricating artworks to have a public artwork by a local artist. All parts of the processes where transformed to bring Finn’s vision into the public realm. Every agency should ask itself how it could change such that the Finn’s are the norm and the pride, not the exception.

Thanks to Kelly Haferman photos, John Nation and Michael Kimmel of Waterfront Development Corp.

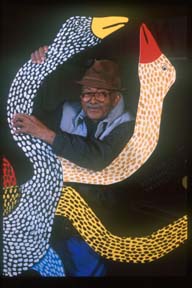

Born in 1917 in Clio, Alabama, Finn came to Kentucky in 1940. He settled in Louisville and worked as a laborer for 26 years — jobs in construction, pumping gas, loading barges. His artwork began as toy making for his five children in the 1950s. Scraps of work became animals, especially chickens.

In 2000, Louisville wanted its own “Cows on Parade”. Instead of fiberglass Louisville sluggers decorating the sidewalks, the City turned to Marvin Finn and asked, “Could we have a “Flock on Finns”?

By 2002, multiple sculptures by Finn had been reproduced and enlarged in painted steel. A dusty patch of ground was found in the new award- winning Waterfront Park by Hargreaves Associates (another essay.) on the Ohio River.

Unfortunately, I could not find any images of the “Flock of Finn” through any official website. On the Waterfront Park website, none of the artwork is presented or mentioned. Even the designer, George Hargeaves, is only one tiny phrase in the timeline section.

According to Louisville, Albertus Gorman. In her essay, “Black American Folk Art, Origins and Early Manifestations”, Professor Regina Perry mentions that wood sculptures and the use of mixed media are characteristics of the Yoruba peoples of West Africa. A typical Finn rooster is made of scrap wood and then specially painted. Each feather of the bird’s body is rendered as a single dash mark of the paintbrush. The visual effect is much like beadwork, which is also an important West African link. Finn also adds other materials to his work. It is not uncommon to find a crowing rooster with a small nail representing the bird’s tongue. The use of nails, tacks and shells are integral to West African sculpture traditions.

I always find use of the term “local artist” troubling. Everyone is local to somewhere. What we really mean is not nationally known or recognized.

Glenn. I love the post about Louisville. Yes, exactly. Not the old resentful regionalism but a dig-down-and-waken look at what’s going on across the country.