In the mid-1990s, I visited a scary Johannesburg. The hotel had non-uniformed armed guards carrying guns. Drug dealers were on hand. Unlike other parts of South Africa, everyone spoke of the dangers after dark. Yet, art went on. I can see in my memory a black man and a white man playing tennis inside the main dining room of Jo’burg’s abandoned historic prison. During the performance, the men talked of their different lives and their confrontations.

At the same moment, whites and blacks admitted to terrible murders as part of Bishop Tutu’s and Nelson Mandela’s “Truth and Reconciliation” process. With several hundred South Africans, I spent two days in the meeting hall of Port Elizabeth listening to confessions of killings. Was the art in the prison or the hall? For the outsider, especially one that grew-up in the socially segregated southern USA, both were emotionally vibrant.

In 2006, Jo’burg passed a public art ordinance that is 100% American vanilla. In the preamble: “…Public Art provides a means of celebrating Johannesburg’s unique culture, diverse communities and rich history. It offers shared symbols which build social cohesion, contribute to civic pride and help forge a positive identity for the city.” In just ten years has the passion so drained from life? Or was life so full of the tensions of art, that art was asked to become a generic warm blanket?

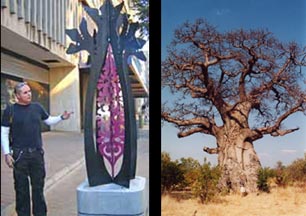

The first official public art was unveiled in July 06 with nine steel trees on Juta Street created through a collaboration of students and artist Claire Regnard. According to the City website, the works cost only $10,000 as apart of a $1.3 million cultural enhancement before the 2010 World Cup finals in Johannesburg.

Like the public art ordinance, these sculptures are the type that give public art a bad name amoung the museum world. They are almost powerless artistically, yet justified administratively by collaboration with children and by populist colors. Equally empty is the simplistic anti-AIDS mural by artists Tshepo Mofokeng and Mandla Manana that was the second public art project. (Strangely, none of the articles on the project make reference to Baobab trees so obviously reflected in the sculptures proportions of fat trunk to branches. The bright centers recall the reality and mythology of the life (80% water) in the heart of the massive trunks.)

Both are typical kinds of projects to engage the community at the beginning of a new program where everyone – artist, community and politicians – is paying attension. But after the intensity of the life and art in the 1990s, the absence of social confrontation or emotional stress is shocking. Like many American programs, I can only understand this as repression, but through absence rather than action.

(I hope Johannesburg will forgive me for assaulting a number of timid American public art programs via Jo’burg’s first official projects. Visit Visual Essays for More Photographs)

Cascoland Festival, Johannesburg, March 2007

Tire Art by Jan Korbes

Unrelated to the official public art is the second Cascoland Festival, a weeklong collaboration of all art forms between residents surrounding Drill Hall and artists from the Netherlands and South Africa. The public art is very architectural and hands-on, so typical of liberal Dutch artists during the last 20 years. Everything is nomadic – tents, plastic pools, streets games, tires – in which the art is the placement. In Drill Hall, the tents landed on the roof and the pool crashed into the basement.

The first Cascoland Festival in Capetown had more imported high art, Dutch style. Projects include daily life in a pristine white bubble, a star bath in the plaza, a radio broadcast speaker tower and self-stenciled houses.

Art Installation by Bert Kramera

Clarifications sparked by a question from Regina Hacket of Seattle.

The tennis match was part of an elaborate performance art work that encompassed the entire prison. The tennis match was an art performance written by an artist.

Yes during the moment of historic change artists must struggle to compete with the poetry of life itself. The life of SA was more than many artists could imagine. In the prison work, the artist was finding her voice in dialogue with life around her.

Today, the public art in SA is just like the work in USA: Empty of any mandatory dialogue with its world. But at least in SA, the artwork can be seen as a pleasant break.

Dear Glenn,

Are those Johannesburg Baobabs any better or worse than those damned cows and whales that suffice as public art in many American cities? At least these have some dignity. They look like they employed people for a while. At least they aren’t trying to redeem their ‘art’ through telling people that non-profit agencies will benefit by their sale. I like the Baobabs far better than some things. So they’re no Calder-or Moore, maybe it is time to give new developing (redeveloping) arts communities some encouragement. Nobody wants depictions of blood and guts art in the streets, do they? I don’t.

K.

Reply from the artist Claire Regnard in Jo’berg.

When I was first approached to assist in the designing of these sculptures one of the first feelings I had, was that we needed to create pieces that ‘the man on the street’ could relate to. The majority of South Africans do not come into contact with art, not in museums or galleries. I did not create them for any other reason but for beauty, and a reflection of life. Not hardship or strife, which has been a part of most of us living in South Africa’s life. It’s sad that you personally don’t feel the passion of what we managed to produce with such a small budget.

While I was installing them on the street last year, I was in contact with people who lived, worked and walked the streets. The people who live and worked (car guards) on Juta Street, commented on the fact that they where proud we had chosen their domain, hence we have had no vandalism to date. The people who walk the street, stop and look, sit at their bases and read newspapers and I’ve seen school children on there way back from school playing with them.

For me that has made the project successful. They are part of the street culture, not reminding us of hardship and pain, just being what they are.