This summer, Lawrence Argent installed “Ghost Trolley” in Aurora, Colorado, at a moment when rebirth of trolley systems or “light rail” has achieved messianic proportions throughout the USA. After nearly 100 years of automobiles, light rail is the mass transit system of choice for the suburban middle class moving back to the city centers. All planners under 40 years old assume that the renovated American cities of the future will be organized around light rail stations with heavy rail linking cities within metropolitan regions. All this environmentally intelligent dreaming (or “smart growth”) is currently tiny compared to the expanding automotive sprawl and the coming re-investment in broken bridges and cracking concrete pavement.

This summer, Lawrence Argent installed “Ghost Trolley” in Aurora, Colorado, at a moment when rebirth of trolley systems or “light rail” has achieved messianic proportions throughout the USA. After nearly 100 years of automobiles, light rail is the mass transit system of choice for the suburban middle class moving back to the city centers. All planners under 40 years old assume that the renovated American cities of the future will be organized around light rail stations with heavy rail linking cities within metropolitan regions. All this environmentally intelligent dreaming (or “smart growth”) is currently tiny compared to the expanding automotive sprawl and the coming re-investment in broken bridges and cracking concrete pavement.

As is now epic myth, General Motors bought the Los Angeles trolley companies, dismantled the tracks, substituted bus lines and lobbied for highways. It’s not that evil. American mass production and higher wages made the automobiles relatively affordable and matched the American passion for individual freedom of mobility. The trolley lines’ profitability was dependent on the crowded and aging tenements, rowhouses and apartments. Only the landlord would avoid the fresh air of the suburbs and convertible.

In line with the rest of the nation, the last trolley to Aurora rolled in 1932 on the tracks underneath the site of the “Ghost Trolley”. In Denver, the streetcar system began in 1883 and was in full operation by 1900 through out the Denver. Aurora hopes the Denver metro’s light rail system will pull into its downtown before 2020.

Argent and the Aurora Public Art Program must be fully aware of the moment, although I do not know – or care in regards to this essay – their political or conceptual involvement. What matters to critical assessment of public art is the existence of the moment and the artist’s AND the agency’s action within this moment. Without engagement of the moment, the artwork become “art in public places”, not public art. This is lengthy discussion that does not degrade “art in public places”, but just strives to clarify a critical attribute that is frequently dodged, ignored and generally hoped will disappear by sponsoring agencies. Worse, than providing disliked artwork, might be artwork with an ambiguous message that speaks to an obvious or ignored cultural transformation. (Since the cultural wars of the 1980s, direct negative commentary or sexual messages have been censored by funding agencies.)

In our artistic tradition, significant public artworks (and private ones) are associated with the moment: i.e. the Statue of Liberty with the hope of European immigrants. As the moment sinks from significance, so can the artwork.

To determine the value in the moment let’s use Kenneth Frampton’s comparative method. Matthew Dehaemers’s 2003 “Point of Departureflying streetcar in Kansas City seeks a similar function in the same civic moment as Argent’s “Ghost Trolley” in metro Denver. (Argent tells me he never saw Dehaemer’s temporary project. But this is irrelevant to my assessment of either work in this age of vernacular art.) Kansas City was in a decade long fight between a citizen activist for light rail and the city’s establishment that was resolved in November 2006 when a sales tax increases was passed by the voters without City support.

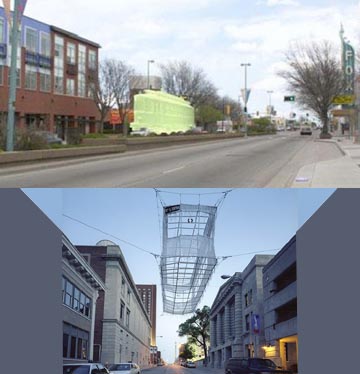

Argent’s Ghost Trolly, ’07 and Matthew Dehaemers’ Point of Departure, ’03

What is the same?

Real scale of an early 20th century trolley

Located in the center of the street like a trolley

Uses “white” to suggest the spirit attribute

No illusion of motion. Static fact.

Made when light rail was under discussion in both cities

What is different?

Ghost Trolley……Point of Departure

Frosted composite materials……Net of cotton cords

On the ground in the median……Suspended over the street

Flattened axonometric image ……Dramatic lines in perspective

Solid……Transparent

Industrially carved……Handmade like a grandmother’s shawl

Light rail under construction……Light rail rejected by voters

Both works are factual without any real interpretation. They declare merely “trolleys were here”. Dehaemer’s handmade quality with the antique fringe and its flying position is more evocative of an actual ghost. Argent bets on the clever 3-D illusion.

Karl Yoder Mural in Philly and Typical Tourist Trolley Today

The question for me is why both artists chose the historic trolley instead of the Buck Roger’s streamline or the Japanese bullet train. The historic trolley has been degraded by its overuse as the standard warm weather tourist transport in every American city. Where is the connection to Tennessee Williams “A Streetcar Named Desire” so easily referenced by Mona Caron in her 1998 mural? Where are the thousand filmic chase scenes with people jumping on and off the trolleys? Especially the “Streets of San Francisco”? If the image is historic, then a connection Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton? Where is the energy of the train in Kansas City’s Thomas Hart Benton paintings and prints of the 1930 or 40s? Or his reality of the workingman’s life that used and serviced the trolley. Where is GM or its equivalent?

Brando still from Street Car Named Desire and Mona Caron “Desire” train mural (photo Eric Haas)

Why are public artist getting away with only the facts? I might say that agencies are afraid of the interpretations, but the fact object is a dominant historic trend of 50 years of art at least since Jasper John’s target and flag and Oldenburg’s baseball bat. Beyond the oversized element (to be discussed in the next Argent essay), the fact object confronts the audience with the value of that common thing or situation so frequently overlooked. The confrontation requires surprise at the object selected and the location displayed. Both Argent and Dehaemer fail to surprise us as the moment expected the rebirth of trolley in exactly those places.

Trolley in House in 1952 and Abandoned in 2006

In Aurora while Argent was fabricating “Ghost Trolley”, an amazing event occurred and then disappeared. A hundred year old trolley was re-discovered boarded-up suburban house. In 1950, Edwin Perrott bought a trolley for $50 and built a house around it, converting the interior to a sitting room and bedroom. A classic American tale of reuse and invention on private property in the Western USA where ABSOLUTELY NO ONE or THE GOVERNMENT had the right to tell YOU WHAT TO DO. In 2006, as Sgt. Franklin Michelson inspected the abandoned house, he found and informed the City of the trolley in the house. Within a few months, the Historic Society had raised the money to move the trolley from the house with a pledge to restore the trolley. For reasons of failed imagination, the restored trolley – another fact – was more important that the complex story and imaginative potential of the trolley in the house. Truly a “spirit” that speaks to the cultural abandonment of the mass transit and the trolley’s reincarnation at the heart of the suburban freedom served by the automobile.

JUST TO KEEP THINKING

Both Argent and Dehaemers have created works with comparible attributes to other contemporary artists – most likely without awareness of the other artist. Again, who cares that the techique has been used, but rather how has the techique been modified for the situation? Does the use of the technique enhance the message of the artists and its moment?

Argent’s “Confluence”, 2006, Fort Collins, CO, USA and Hew Chee Fong/L.M.Noonan’s “Stillwater + Rocksack”, 1999, Carindale, QLD, Australia

Argent’s “Confluence”, 2006

Venturi in Philly – Jenson in SeaTac, WA – Dehaemers in Kansas City

UPDATE OF SORTS: See Discussion with Ries in the Comments

Seattle Art Musuem Olympic Sculpture Park, where Mark Dion did a piece about a Nurse Log (“Neukom Vivarium, 2007”), and many people brought up Buster Simpson’s Nurse Log (“Host Analog”, 1991) of ten years or so before, in Portland. General consensus was the subject had enough inherent interest to attract two different artists, at two different times, and no copying, or, in fact, even awareness of the other, had occurred. From Ries.

Buster Simpson, Host Analog, 1991, Oregon Convention Center, Portland, Oregon

Mark Dion, Neukom Vivarium, 2007, Olympic Sculpture Park, Seattle, Washington

In 1991, Buster Simpson planted Douglas Fir, Hemlock, and Western Red Cedar seeds onto an eighty-foot-long Douglas Fir nurse log.

In 2007, Mark Dion’s work features a 60-foot decaying “nurse log” enclosed in a greenhouse. Cycles of decay and renewal will be evident to current and future generations of park visitors, who can observe the thriving bacteria, fungi, lichen, plants and insects with microscopes and artist-designed field guides.

FINAL COMMENT

Because Buster Simpson is a lifelong member of the Seattle community and one of the American founders of public art, I find it insulting that Dion was permitted to make and exhibit this work in such a high profile situation. The Seattle Art Museum should have told Dion – we are sorry, but we would like a different work of art. Artisticly, I think it is great to have two similar works, but socially, another local Art Museum with international ambitions slaps the local artist in the face. Excuse me, but it just sucks.

Digg it……. Save to Del.icio.us ……. Save to Technorati

Dehaemers installation was exhibited for five months in 2003. Doesn’t the intentionally temporary nature of his piece play more significantly into this comparison?

From Ries

I am confused as to where you are going with this.

I do not believe there is a lot of meaning to the fact that two artists chose to use antique streetcars in their pieces.

Artists around the world, thruout history, have happened to use similar subjects for a variety of reasons.

But what makes Art, in general, interesting, is that even given the exact same assignment, in terms of size, shape, material and subject matter, no two artists will ever make the same piece.

And Vive La Difference!

I would like to point out, however, that the commissioning bodies, which, in at least of one of these instances is a light rail building entity, tend to subtly, and sometimes not so subtly, push artists towards a relatively limited set of art subjects.

Under the guise of “community relevance” or “local history” or just plain conservatism, many many public art projects tend towards pretty dry, and often cutsey historical subject matter.

I have certainly been guilty of this myself, as has virtually every other public artist I know- as Ken Kesey used to say, “Dont push the river- it flows”, which means, its a lot easier to go along, and get the commission, then to get rejected and never build that better idea.

This is a subject I would like to see you address-

The degree to which the subject matter and execution of public art is determined, not by the artist, but by the “educational”, “historical”, and general “dont rock the boat” nature of the selection and commissioning process.

Sepia toned photos of the earliest inhabitants of the neighborhood, featuring Model T’s and, yes, antique trolleys, are always crowd pleasers, and safe to boot.

Weiss Response

I am not sure where I am going, but I know that nobody talks about the reality of similarity in the contemporary art market. (In the traditional crafts and bronzes- animal sculptures and children playing – similarity is a given starting point.) I did not get anywhere in the essay regarding the value of the difference between the two works because the comparison drove home the “fact” nature of the work and the interpretative silence.

If the agencies subtly steer the artists toward community meaning of a assumed nature, then do not the artists have a role in interpreting that meaning and its specific attributes of that place or that time?

More Reis

Back to front-

Certainly, the artists have a role, and that interpretation, and the success thereof, is what separates a good artist from bad.

This is true with any art, of course, but in traditional studio/gallery art, all of the meanings and attributes are selected by the artist.

However, on public art projects, it is not uncommon to be told the artwork must be in the high school team colors (I am not kidding about this, Alaska one percent had a whole rash of these a couple of years ago).

Or using leaf imagery. Or you MUST include references to the historical asian community. Or to the meatpacking aspect of the neighborhood.

These kinds of built in rules are very common. And yes, it does indeed separate the men from the boys, or the the women from the amateurs, or whatever, to see who can jump thru these silly hoops and STILL make a good work of art.

Compromise, on many levels, seems to be much more of a feature in public art than in any other form of art.

As for mining the same vein- an interesting discussion on this ocurred with the opening of the new Seattle Art Musuem Olympic Sculpture Park, where Mark Dion did a piece about a Nurse Log (“Seattle Vivarium”), and many people brought up Buster Simpson’s Nurse Log (“Host Analog”, 1991) of ten years or so before, in Portland. General consensus was the subject had enough inherent interest to attract two different artists, at two different times, and no copying, or, in fact, even awareness of the other, had occurred.

More Weiss

This is an important concerned of forced subject matter, not because of the forcing, but in how the subject matter was selected. Was it invented by the administrator based on her/his knowledge or assumptions? Was it based on community surveys or focus groups – AND – were the people given a true set of options or the education how to discover complex and intimate themes from the community? Has the administrator established a situtation where the community is open to complex and ambiguous intepretations by the artist?

I did not know about the two “nurse logs”. In my opinion, Mark Dion should have known about Simpson’s log and then made a better work because of it. I bet Dion would have never made the work for Seattle if he knew about Simpson. The contemporary art world is afraid of duplication, but this will change. Too many artists worldwide with too much shared knowledge.

More Ries 2

I find it interesting that you say “not because of forcing”.

Are you saying that the circumstances of public art projects justify, or in fact require, that the subject matter be preselected by the administrators?

I can see a list of banned subjects- sex and drugs and rock and roll, no depictions of violent deaths in the elementary school, and so on.

But it is my opinion, speaking from my highly biased viewpoint as an artist, of course, that the fewer restrictions the commissioning body puts on the artist, the better work they receive in the end. Assuming, of course, that they pick a good, or hopefully even great, artist to begin with.

The pieces I have done that I am the least proud of are always the ones that have the tightest perimeter drawn by the client.

And the ones I like the best, and, often, the public seems to as well, are the ones where I proposed something they hadnt thought of. When the architect says- “you must make your art in this rectangle of wall, exactly 11′ 5″ x 6′ 3”, the works are usually much less than they could be.

When the artist is allowed in early, with an architect and client who is willing to share a bit of the spotlight, better work usually results.

Weiss Response 2

Sometimes the purpose will be established especially in memorials to events or people. But beyond that, does every artist need to be an excellent researcher and manager of focus groups?

I agree that the X marks the spot for artworks is awful when the X is a lazy solutions by the architect and administrator. Sometimes the X might be the right spot.

More, More Ries

Never say final.

The Dion project is remarkable for other reasons as well.

First, it is the only sculpture I am aware of that the artist sold the “naming rights” to. Much like the Staples Center in LA, or Safeco Field here in Seattle, the artwork is called the “Nuekom Vivarium”.

It is titled after the major donor of money to build the piece.

To me, this raises a lot of issues about the commercialism of art in musuems.

The naming of buildings, rooms, and plazas after donors, while somewhat vain and overblown, is one thing- but actually naming the artwork after the money man?

Weiss: Very interesting.

Good dialog, Reis & Glenn.

Thanks for bringing up Buster Simpson’s PDX piece, Reis. I too, thought the slight was awful but not surprising given the players. Pacific NW provincial insecurity strikes again.

Re: context discussion & making strong public art. I think you’re on target, Glenn, w the critique aimed at the silencing experienced post- culture wars. We’re in an odd monumental moment w kitschy symbols of bygone eras arranged as ‘safe’ references to revisionist histories. Call it the ‘paint by numbers’ approach to public art where ‘approved’ subtexts appropriately represent the PR values of the client.

Good, challenging work arising within such an atmosphere is usually an accident & probably won’t go unpunished.