“There is nothing fine about being a child: it is fine, when we are old, to look back to when we were children.”

Cesare Pavese, This Business of Living

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

“There is nothing fine about being a child: it is fine, when we are old, to look back to when we were children.”

Cesare Pavese, This Business of Living

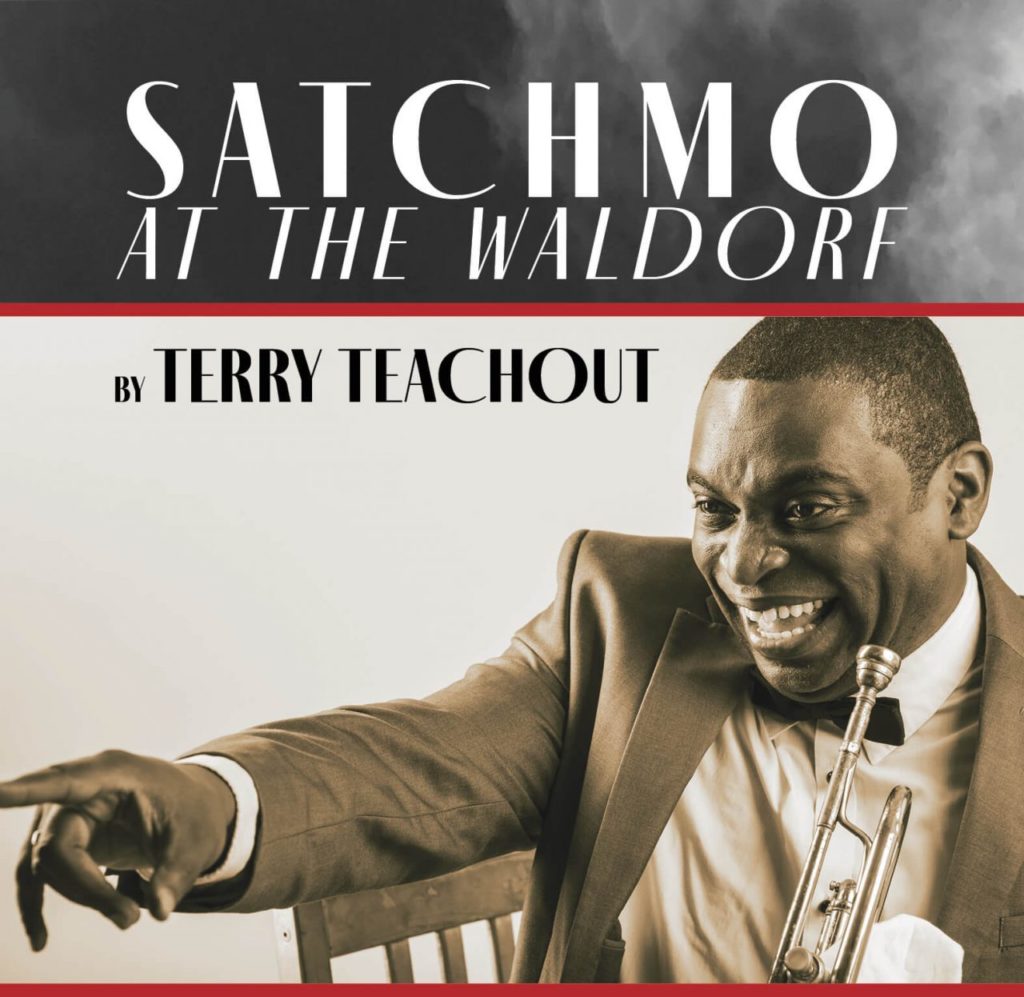

I long ago lost count of the number of times that Satchmo at the Waldorf, my one-man-three-character play about Louis Armstrong, has been produced. I do, however, take note whenever I hear of an upcoming staging, and it so happens that there are two in the works, both of which will be streamed.

The first one, performed by Douglas Scott Streater and directed by Sharon Graci, will be mounted by PURE Theatre, a company based in Charleston, South Carolina, starting on December 17 and running through January. The second one will be produced by American Stage Theater of St. Petersburg, Florida, starting in February. (No other details have been released.) I know nothing about either of these theater companies, and neither one has reached out to me about producing Satchmo. That surprises my friends, and it used to surprise me until I realized that my first play is like a grown child who has gone out into the world to make his own way. All you have to do to produce it is get in touch with my publisher and apply for the rights to stage the show. I have nothing to do with it—I just sit back and, in due course, collect the royalties.I do, however, plan to watch both new versions on my laptop. So far as I know, Satchmo has never been webcast, and I’ve yet to see a production with which I wasn’t directly involved in one way or another. I’m very curious to see what actors and directors who don’t know me will make of my play. It’s an extremely demanding role, and the last Satchmo I saw, in Houston in 2019, was a production I directed myself, so it stands to reason that I have strong opinions about how to do it. On the other hand, I’m completely open to new approaches—I’ve seen Satchmo directed by three other people, and I liked all three versions—and I expect to learn new things about my play when I see it done by Pure Theatre and American Stage Theater.

It is strange to think that Satchmo is nearly ten years old. It never occurred to me when I staged the first workshop performance of the first half of the play at Florida’s Rollins College on February 1, 2011, that Satchmo would go on to be produced off Broadway and throughout America (though not yet in Kansas City or St. Louis, which makes me sad—I would dearly love to see it done in my home state). Nor did I suspect that making theater would become so important a part of my middle age, much less that I would make my debut as a professional stage director at the age of sixty.

I wish my mother had seen Satchmo, but she was no longer capable of traveling by the time it came to the stage. Fortunately, Hilary saw it many times, and it made her proud to know that her life’s companion had taken such a bold step forward. She was responsible for it, after all, though she never admitted as much: it was Hilary who insisted that I could do more than merely review plays, and it delighted her that she was right. Would that we could watch PURE Theatre’s Satchmo together next month! Alas, it cannot be, but I do plan when the show is over to lift a glass and say, with the fullest of hearts, “You did this, my beloved. Thanks.”

Julian Bream talks about and plays Malcolm Arnold’s Guitar Concerto live in 1991, accompanied by Barry Wordsworth and the BBC Concert Orchestra:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“Whatever the old girl says, do—do it!”

Charles Dickens, Bleak House

* * *

Lydia R. Diamond’s “Smart People,” a hard-edged satire of life among the academic multiculturati, was first performed off Broadway in 2016 in a production directed by Kenny Leon. I praised the play at the time as “intelligent and provocative enough to put you in mind of Tom Stoppard,” and I wasn’t even slightly surprised to see it taken up in short order by regional theaters. A four-character play with minimal scenic requirements, it also lends itself to small-scale bare-bones production, which makes it ideally suited to webcasting. Accordingly, Wisconsin’s American Players Theatre, America’s finest classical theater festival, has now put “Smart People” online as part of the company’s “Out of the Woods” series of Zoom-based play readings….

Directed by Melisa Pereyra, this webcast, like its predecessors in the “Out of the Woods” series, is an unstaged Zoom reading. It is well acted, crisply paced and sufficiently convincing in its own right to confirm my initially favorable impression of “Smart People,” and if you’ve never seen the play, I recommend it to you….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.An excerpt from Writers Theatre’s staging of Smart People:

A scene from NBC’s 1960 telecast of the musical version of Peter Pan, starring Mary Martin and adapted and directed for the stage by Jerome Robbins. The song is by Carolyn Leigh and Moose Charlap:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“To die will be an awfully big adventure.”

James M. Barrie, Peter Pan

Not long after Hilary died, an old friend of mine who is also a psychiatrist said something that stayed with me: “You should try to reach a point where you can see your marriage to her as a blessing.” My Jewish friends have a different way of putting it: May her life be as a blessing. But it was difficult for me to feel that way in the first few months that followed Hilary’s cruelly untimely death, fixated as I was on the sheer wrongness of it. To die a month after receiving the double lung transplant for which we’d spent seven long years waiting—how could that make any kind of sense?

Would that I had found solace in the comforts of faith. Alas, I was unable to drive these terrible lines from King Lear out of my tortured mind:

As flies to wanton boys are we to th’ gods.

They kill us for their sport.

Only in the past month or so have I started to find it possible—on occasion—to remember with joy the good times that Hilary and I shared during the fifteen years of our marriage. Knowing that her life would inevitably be cut short, I resolved early on to fill what remained of it with what we called “adventures,” most of which I chronicled on this blog. We traveled from coast to coast seeing shows for The Wall Street Journal. We drove up Highway 1 from San Diego to San Francisco one summer, and made the same trip in reverse two years later. We spent a long weekend cruising on a windjammer and eating fresh lobster, the food she liked best, so much so that I made sure it was on the menu of every restaurant where we dined on our annual trips to Maine. We stayed in three different Frank Lloyd Wright houses and went to two county fairs (I rented a wheelchair for the day and pushed her from ride to ride). I wrote an opera libretto and a one-man play about Louis Armstrong, and Hilary was in the audience for the opening nights of both shows, as well as the night when I made my debut as a professional stage director. And—best of all—we spent the better part of six winters on Florida’s Sanibel Island, our favorite place in the world.

Hilary was the ideal traveling companion, throwing herself into our shared adventures with contagious gusto. Though she didn’t much care for the novels of Henry James, I think she would have liked these lines from The Ambassadors: “Live all you can: it’s a mistake not to. It doesn’t matter what you do in particular, so long as you have had your life. If you haven’t had that, what have you had?” Knowing that she was destined to die before her time, she lived all she could, and I delighted in dreaming up new ways for her to do so. To see her wonderful smile—it lit up her whole face whenever she was happy—never failed to make my efforts worthwhile.

This is the first Thanksgiving since Hilary’s death, and I’m trying to be thankful for what we had, and grateful that I (usually) knew how happy our life together was while we were living it. The two of us saw Our Town together four times, in Petersborough, Hartford, New York, and Boston, and though we never talked specifically about the question that Emily asks the Stage Manager at play’s end, I feel certain that Hilary was at all times intensely aware of its immediate relevance to her condition: “Oh, earth, you’re too wonderful for anybody to realize you. Do any human beings realize life while they live it…every, every minute?” Hilary did, and because she did, so did I.

Even now, such gratitude doesn’t come easily to me—I’m still bruised by what I went through in the last couple of years of Hilary’s life, when her health started spiraling inexorably downward—but I hope that the adventures we shared will someday be the first thing I think of when I think of her. That will be a blessing.

* * *

A scene from the 2002 Broadway revival of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, with Maggie Lacey as Emily and Paul Newman as the Stage Manager:

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | ||||

An ArtsJournal Blog