“Those who foresee the future and recognize it as tragic are often seized by a madness which forces them to commit the very acts which make it certain that what they dread shall happen.”

Rebecca West, The New Meaning of Treason

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

“Those who foresee the future and recognize it as tragic are often seized by a madness which forces them to commit the very acts which make it certain that what they dread shall happen.”

Rebecca West, The New Meaning of Treason

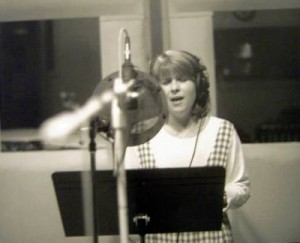

Nancy and I met seventeen months before she died. I was interviewing her for the New York Daily News, and we realized on the spot that we liked one another very much. I took her to a performance of George Balanchine’s ballet version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream a few weeks later, and we went to dinner together after the show, talking until the restaurant closed. From then on we were the best of friends, exchanging regular phone calls in which we heedlessly shared the most intimate of confidences. I can still hear in my mind’s ear her warm alto voice on my answering machine, always starting off with a cheery “Hi, LaMottski here!” (Nancy was the kind of person who spoke in exclamation points.)

I wrote about her many times, but never succeeded in fully conveying her sheer goodness, though I tried hard to capture it on paper. Not that it mattered, for you didn’t have to know Nancy to hear in her radiant singing the kind of woman she was. She called herself “a major-chord singer,” which was exactly right: for all the sophistication of her art, she was still a small-town girl at heart, sweet and generous and uncomplicated, and she knew how to be happy.

As I wrote in The Wall Street Journal when Live at Tavern on the Green, the album of her last opening-night performance there, was released in 2005:

I won’t pretend to be objective about Nancy—we were too close for that—but I was hardly the only critic to know her for what she was. John Simon, one of the toughest customers in New York, said that “she fully fathoms what a song is about, and then, rather than merely singing it, lives it.” Stephen Holden put it a different way in her New York Times obituary: “She brought to everything she sang a clean, clear sense of line, impeccable enunciation and a deep understanding of how a good song could convey a lifetime’s experience.” All this is on Live at Tavern on the Green, along with a special quality I tried to put in words when I wrote in the New York Daily News that she sounded “sincere and sensuous at the same time, as if the girl next door had snuck out at two a.m. to make a little whoopee with her steady boyfriend.”

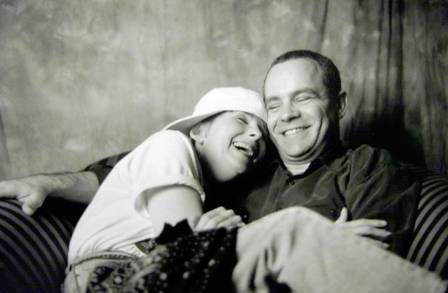

Nancy and I felt from the start as though we’d always been friends. We loved one another deeply and devotedly, though never in a romantic way. She met Peter Zapp, a gifted stage actor, in San Francisco in May of 1995, and I knew as soon as she told me about him that she had found the man of her dreams. I rejoiced with her, and became good friends with Pete once we finally met. (Nancy and I both found it wildly funny that she saw him for the first time when he was playing Roy Cohn in Angels in America.) Theirs, alas, was destined to be a brief love, for her long-precarious health—in addition to metastatic cancer, she had Crohn’s disease and wore an ileostomy bag—crumbled in December. Pete flew back to New York at once, but it was clear by then that she was dying, and I rushed to the hospital to keep vigil with him and a few of her closest friends.

Late that night, the doctors told Nancy that she was near death and offered her opiates to relieve her agonizing pain, explaining that they would send her into a coma from which she would not awaken. Pete had proposed to her the day before, and now she told him that she wanted the morphine—but that she wanted to marry him first. I fed quarters to the pay phone in the corridor outside her room in order to find a priest who could come right over, then stood by her bedside as she and Pete said their vows. She died an hour and a half later.

Losing Nancy was the worst thing that had ever happened to me, and it was not until I lost my Hilary under similar circumstances last March that I experienced anything that surpassed it. As a result, years went by before I could bear to listen to Nancy’s records again. Even now I don’t play them as much as I ought to, something that would have saddened her, though she would, as always, have understood.

I did, however, make a point of playing her records for Hilary, who loved them, and on the terrible night that my own life’s companion died, I posted a link to a medley of two songs from Stephen Sondheim’s Merrily We Roll Along that Nancy had recorded in 1993, knowing that the lyrics summed up everything I was feeling: Not a day goes by,Where’s the day I’ll have started forgetting? Beth sings in the same song, knowing all too well that there is no forgetting such people. To be sure, I no longer think about Nancy every single day, and I suppose it is possible that a time may also come when I no longer think about Hilary every day, either. But I know that each time I do, I will remember them both with tender gratitude for the blessing of their having been part of my life. That is true love.

* * *

Nancy LaMott sings “Moon River,” by Johnny Mercer and Henry Mancini, accompanied by Christopher Marlowe. This was the last song she ever sang, on Charles Grodin’s TV show a week before her death:

Marin Mazzie sings Stephen Sondheim’s “Not a Day Goes By,” from Merrily We Roll Along:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“The life of the dead is placed in the memory of the living.”

Cicero, Philippicæ

* * *

Philadelphia’s Wilma Theater, one of the East Coast’s leading drama companies, has taped a fully staged site-specific production of “Heroes of the Fourth Turning” at a private location in the Poconos, turning the cast and crew into a closed quarantine “bubble” so that they could work together face-to-face instead of taping their performances separately via Zoom or green screens. The result, which looks more like a small-scale movie than an online webcast of a stage show, is a flawless, impressively well-cast production of a work of singular distinction, one for which the word “remarkable” is, if anything, an understatement.

The play, directed by Blanka Zizka, is set in rural Wyoming in 2017. It centers on Emily (Campbell O’Hare), Kevin (Justin Jain) and Teresa (Sarah Gliko), who are in their mid-to-late 20s and are meeting at the off-the-grid shack of Justin (Jered McLenigan), a somewhat older but like-minded man. The young people are all in the familiar process of discovering themselves, but there is nothing else ordinary about them: They are conservative Catholic intellectuals-in-the-making who have been girding themselves for battle in the coming culture wars….

While I feel sure that many of those who saw “Heroes of the Fourth Turning” in New York found the characters, not entirely without reason, to be potentially dangerous extremists, they are far more complicated and interesting than that, for life in urban America has nibbled away at their orthodoxies….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.The trailer for the Wilma Theater’s webcast of Heroes of the Fourth Turning:

Greer Garson presents the 1952 Best Actor Oscar to Humphrey Bogart for his performance in John Huston’s The African Queen. It was Bogart’s first Oscar:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“I don’t claim to know that God exists. I only claim that he does without my knowing it.”

Tom Stoppard, Jumpers

My “Sightings” column in this week’s Wall Street Journal is about large-scale virtual presentations of famous works of art. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

The bad news is “Immersive Van Gogh,” a 500,000-cubic-foot high-tech video installation that opens in Toronto on Dec. 21, in Chicago on Feb. 11 and in San Francisco on March 18. It makes use of 50 digital projectors to show animated versions of “Starry Night” and several of the painter’s other masterworks, accompanied by New Age-style music. The press release maunders on at length about how the visitor (masked and socially distanced, of course) will “wander through entrancing, moving images…truly illuminating the mind of the genius.” I haven’t seen the show in person, but the extensive video clips I’ve viewed online suggest that attending “Immersive Van Gogh” is not even remotely like the intensely involving experience of encountering a painting up close. Instead, the work of one of the greatest of all visual artists has been turned into something more like a giant video game….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | ||||||

An ArtsJournal Blog