• Maud finds the online annotated Moby Dick. Suitable for reading on your iPhone during passive commutes then rising exalted to peer over your fellow subway passengers.

• Not a fresh link but of interest if, like me, you’re a fan of Sarah Hall’s Daughters of the North: Galleycat’s interview with Hall where she discusses the novel’s start as a short story.

* Still a cruel reminder of what once was. But I will not surrender to “morning green tea.”

CAAF: John Keats, John Keats, John, please put your scarf on

Is it just me, or is John Keats everywhere right now? In her excellent Believer essay on novel-writing, Zadie Smith talks about her early identification with the poet and the influence of his example:

I was about fourteen when I heard John Keats in there, and in my mind I formed a bond with him, a bond based on class–though how archaic that must sound, here in America. I knew he wasn’t working-class, exactly, and of course he wasn’t black–but in rough outline his situation felt closer to mine than the other writers I’d come across. He felt none of the entitlement of, say, Virginia Woolf, or Byron, or Pope, or Evelyn Waugh. That was very important to me–I think you may have to be English to understand how important. To me, Keats offered the possibility of entering writing from a side door, the one marked Apprentices Welcome Here. Keats went abut his work just like an apprentice: he took a kind of M.F.A. of the mind, albeit alone, and for free, in his little house in Hampstead. A suburban, lower-middle-class boy, a few steps removed from the literary scene, he made his own scene out of the books of his library. He never feared influence–he devoured influences. He wanted to learn from them, even at the risk of their voices swamping his own. And the feeling of apprenticeship never left him: you see it in his early experiments in poetic from, in the letters he wrote to friends expressing his fledgling literary ideas; it’s there, famously, in his reading of Chapman’s Homer, and the fear that he might cease to be before his pen had gleaned his teeming brain. When I’m writing, especially during those horrible first hundred pages, I often think of Keats. The term “role model” is so odious, but the truth is it’s a very strong writer indeed who gets by without a mode kept somewhere in mind. So I think of Keats. Keats slogging away, devouring books, plagiarizing, impersonating, adapting, struggling growing, writing many poems that made him blush, and then a few that made him proud, learning everything he could from whomever he could find, dead or alive, who might have something useful to teach him.

Also stoking the current Keats-biquity is the publication of Posthumous Keats, which Adam Kirsch reviewed in the New Yorker and which I’m reading right now and adore (so I’m not so much being shadowed by the poet as carrying him around in my purse).

CAAF: Afternoon coffee

I’m currently weaning myself off coffee so consider the post title above as suffused with longing. I’ve spent the last couple days at one cup a day (down from a steady day-long drip) and so feel a little flattened and pre-lingual and Flowers for Algernonish. Yet in the midst of the bleakness a few animating things present themselves:

• The portfolio of poems by Jack Spicer included in the July/August issue of Poetry, the contents of which the magazine has available online (scroll down). I wasn’t familiar with Spicer’s work before — Lowell was, but he knows his California poets — but I’m completely enamored. A couple to explore are “Any fool can get into an ocean…” and “Imagine Lucifer.”

The magazine notes that a volume of Spicer’s collected poetry, My Vocabulary Did This To Me (that title is taken from the poet’s reported last words), is forthcoming from Wesleyan University Press this fall. A collection of his lectures on poetry, The House That Jack Built, has already been out for some time. You can read an excerpt of one of the lectures here, although I recommend reading this introduction along with it as well as this brief bio of Spicer.

• A while back Rockslinga had a sampling of quotations from Zadie Smith’s essay on novel-writing in the June Believer. I finally picked up a copy of the magazine and I’m so glad I did. Originally given as a lecture at Columbia University, the essay’s one of the most helpful pieces I’ve read about long-haul fiction writing, a nice blend of practical advice with the abstractly inspiring. Unfortunately, it’s only partly available online, which doesn’t do you much good at your desk right now, does it? So until you can procure your own copy, you can read Smith’s very fine essay on Kafka in the current issue of New York Review of Books.

Smatterings elsewhere:

• As the future of the L.A. Times Book Review is considered, Mark “TEV” Sarvas proposes a possible new incarnation for the review as an online powerhouse a la The Guardian. Discussion is invited in the comments, and I point it out as it’s interesting to consider how papers will/ should adapt their book coverage in the future. (Aside: If you’re not reading it already, the L.A. Times book blog, Jacket Copy, is excellent.)

• Fernham provides a report on a lecture she attended on the Borges translation of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own (short version: liberties were taken).

BOOK

Elaine Equi, Ripple Effect: New and Selected Poems (Coffee House Press, $18). This effervescent collection, which gathers two decades of Equi’s work with Coffee House Press as well as a handful of early poems, is one of those happy books that you can open to just about any page and find something to delight. Of her work, Equi has said, “I like the fact that for the most part, my poems are pretty accessible.” And it’s true; there’s a Rumi-esque directness to the work here, as well as a playfulness and wit, that’s wonderfully light-footed and sure (CAAF).

CAAF: Ovidian query (updated)

I have a question, and I’m hoping one of you kind readers can help me out. Wondering, which translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses is this snatch of “Jason and Medea” from?:

So she waited three nights till the moon came full and the round circle shone brightly down on the world, and then she went out of the house in flowing robes and barefoot, hair streaming over her shoulders; all alone into the midnight stillness, while the birds and beasts and men reposed in deepest slumber, with never a stir in the hedges, never a rustle in the silent leaves, never a motion of air, only the glitter of starlight.

I came across it a while back but haven’t been able to track down its source. I have Allen Mandelbaum’s translation, which renders the same section this way:

The moon was three nights short of rounding out

its horns. But when its circle was complete

and shone in full upon the earth, then she,

in a loose robe, barefoot, her hair uncombed

and unadorned, went out to wander through

the silences of midnight. Men, birds, beasts–

were all held fast by deep tranquility.

The hedge did not murmur, and the leaves

Not stir; the humid air was motionless.

Only the stars were glittering…

If you know the source of the top one, please shoot an email my way (caaf at artsjournal dot com).

UPDATE: It’s the Rolfe Humphries translation — thanks, Dave Lull!

CAAF: Daughters of the Cumbrian north

Bless Jessa Crispin for this review of Sarah Hall’s Daughters of the North. It’s a great novel — well-paced, thought-provoking, beautifully written — the kind of novel you finish and immediately want to make all your friends read. Except the first couple times I tried to pass it on, my friends ran fleeing from the book, afraid it was The Handmaid’s Tale revisited. Because like Handmaid’s Tale, Hall’s novel is set in a dystopian future where, among other bad things, women are fitted with metallic doohickies that keep them from reproducing. But unlike Handmaid’s Tale, Sarah Hall’s novel isn’t, well, boring.

As Jessa writes:

I am aware that as a human being, and especially as a woman, I am supposed to like Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. But when I read her 1985 novel of women living in a repressive theocratic regime, forced into either celibacy or involuntary breeding, all I could think was, “OK, so when do these women start stabbing people?” I like a good dystopia as much as anyone, but I prefer mine to come with an organized resistance army.

Exactly! I love Atwood, but I’ve always ranked The Handmaid’s Tale as my least favorite of her books (with The Blind Assassin at the top). It’s been a while but in my memory reading it was like taking a long forced march through flat, didactic country. Like reading The Fountainhead, where you stagger through the long speeches and philosophy desperately hoping for another scene of Howard Roarke and Dominique What’s-Her-Face throwing down.

In a Q & A that appears in the back of Daughters of the North, Sarah Hall says she set out to write a book that “[took] a look at the relationship between war and society and ask several questions. Under what circumstances might we have to turn to violence? Do we renege on our claim to be civilized when we go to war? Can we go to war in the defense of civilization? When is war right, and when is it wrong? And can women make good soldiers?” All big questions, but what I appreciated is how fully digested they were into the novel, and that the novel, in fact, remained a true novel: rich and engrossing and expressive of ambivalence, or negative capability. No polemic to duck, no long speeches to skip. (If anything, the novel’s chief flaw is its brevity; the ending is overly rushed and abrupt and a couple of the later narrative lines — such as the one with Chloe and Martin, if you’ve read the book — are advanced too quickly.)

One reason I think Daughters of the North works so well is how rooted it is in a very specific landscape, the Lake District in Cumbria in the north of England. The region colors not only the setting but the disposition of the characters — individual freedom may not make it to the future, but regional differences do — as well as the flavor of the novel’s sentences. Take this description as the novel’s heroine, Sister, leaves town:

Past the settlement border, in the lower area, the roads had deteriorated. They were much worse than I had imagined. In their years of redundancy they had sagged and rucked. Whole sections had been pulled away by the floods. They felt loose underfoot, like scree.

It’s the “rucked” and “scree” I like. Hall never overdoes it — you never feel like you’re being forced to eat an Anglo-Saxon dictionary — but she has a lovely, aware way of making the prose fit the landscape.

And when the landscape is described it’s with a beautiful, exacting simplicity:

An owl was flying over the grassland, sweeping down towards the ground and then up. Its white, clock-like face hovered gracefully, while its wings worked hard and silently in the air. For a second I caught a reflection in its eye, a weird flash of yellow-green, like a battery light flaring on then off again.

In that same back-of-the-book Q & A, Hall is asked to describe “the importance of Cumbria in your work,” and she answers:

My agent and editor have coined this phrase for my writing — “geo-fiction” — because landscapes feature so strongly in the novels, be it Morecambe Bay, New York, or Cumbria. I keep returning to the north of England in my work though. It’s difficult to say what it is about it that I find so compelling– but I don’t think it’s the fictive romantic notion of the Lake land. I don’t suffer from any romantic illusions about my home turf (stillborn lambs and filthy rains aren’t all that sublime), though I don’t deny its drama. I suppose being brought up in such a remarkable, natural, and feral place — my home was very remote and I spent most of my time outdoors, so you could say the land in part raised me — I now feel beholden to include it in my work.

RELATED: Listen to the Bat Segundo podcast with Sarah Hall.

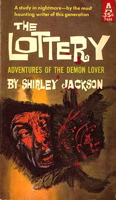

CAAF: The morning of June 27th was clear and sunny…

As Lauren notes (see the July 23rd event), this summer marks the 60th anniversary of the publication of Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery.” Through sheer coincidence, I recently re-read the story for my book club, along with Jackson’s masterful last novel, We Have Always Lived in the Castle.* If you can, it’s worth it to check out the Penguin edition of We Have Always Lived in the Castle, which features a great, perceptive introduction by Jonathan Lethem (sadly not available online).

As Lauren notes (see the July 23rd event), this summer marks the 60th anniversary of the publication of Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery.” Through sheer coincidence, I recently re-read the story for my book club, along with Jackson’s masterful last novel, We Have Always Lived in the Castle.* If you can, it’s worth it to check out the Penguin edition of We Have Always Lived in the Castle, which features a great, perceptive introduction by Jonathan Lethem (sadly not available online).

The precise anniversary of “The Lottery” is tomorrow, in fact. The story was originally published in the June 26th, 1948 issue of The New Yorker — a date that neatly coincides with the story’s first line — and, as Lethem notes in the introduction of We Have Always Lived in the Castle, its appearance caused a storm of controversy. Subscriptions were cancelled, and Jackson received bags of hate mail “denouncing the story as ‘nauseating,’ ‘perverted,’ and ‘vicious.'” (According to its Wikipedia page, the story was even banned in South Africa.)

1948 is also the same year The New Yorker published J.D. Salinger’s “A Perfect Day For Bananafish,” another story that ends with a rather shocking, unexpected death. I’m sure some enterprising PhD thesis has already been done on the topic, but I’m curious about how both stories relate to the field of psychology as it stood in the late ’40s: Behaviorism ascendant, Freud and Jung still in the air and about to rise again. Like most of Salinger, “Bananafish” can be read as a flat rejection of psychology’s ability to ever explain the mysterious self, whereas Jackson seems to have embraced the field, as if she used its concepts and terminology as a jumping-off point for her art. Haunting Of Hill House, for example, reads like a hothouse catalog of Freudian concepts. (Interesting to note, though, that “The Lottery,” which could serve as a case study in the brutal pathology of group think, anticipated the Milgram experiment by about 13 years.)

As Lethem writes about Jackson’s work:

Though she teased at explanations of sorcery in both her life and her art (an early dust-flap biography called her “a practicing amateur witch,”** and she seems never to have shaken the effects of this debatable publicity strategy) Jackson’s great subject was precisely the opposite of paranormality. The relentless, undeniable core of her writing–her six complete novels and the twenty-odd fiercest of her stories–conveys a vast intimacy with everyday evil, with the pathological undertones of prosaic human configurations: a village, a family, a self. She disinterred the wickedness in normality, cataloguing the ways conformity and repression tip into pyscyhosis, persecution, and paranoia, into cruelty and its masochistic, injury-cherishing twin. Like Alfred Hitchock and Patricia Highsmith, Jackson’s keynotes were complicity and denial, and the strange fluidity of guilt as it passes from one person to another.

RELATED LINK: In “Monstrous Acts and Little Murders,” another, earlier piece by Lethem about Shirley Jackson, he talks about living in North Bennington, Vermont, which provided the setting for “The Lottery.” While the town held a grudge for a while, it seems to have forgiven Jackson her trespasses.

* About half our club had never read the story before, which surprised me. I thought no one escaped junior high without writing at least one five-paragraph essay on “The Lottery.”

** Speaking of witches and Shirley Jackson: My reading of We Have Always Lived in the Castle has set me off on a Jackson kick. In my library’s holdings I was surprised to come across a book written for children called The Witchcraft of Salem Village. I’m sure I must have read it as a kid — I was ghoulish and read everything I could about Salem, desperately hoping for illustrations of the hangings, pressings by stone, etc. — but I hadn’t connected its author as being that Shirley Jackson.

CAAF: Red pants, silver shirt?

Can it have been 15 years since Exile in Guyville came out? Yes, it can. The album is being re-released today, and in honor of the occasion I thought I’d share Phair’s setlist from one of her very first shows, when she appeared as part of a showcase put on by Matador Records at Irving Plaza on July 23, 1993.

I was living in Massachusetts then, working at the Golden Nozzle Carwash post-graduation, and drove into New York with some friends for the show. According to this New York Times review of the concert, Pavement, Moonshake and members of the Silver Jews also played, which I have absolutely no memory of. Alex Ross wrote the Times review, and he describes Phair as “a distinctive singer and songwriter disadvantaged by an overloud backing band.” As I remember she was also out of tune and visibly ill at ease on the stage, standing stiffly front and center for most of her set.

My friend Shana, who doesn’t remember Moonshake and Pavement playing either (where were we?), tore Phair’s setlist from the stage after she performed and was good enough to send along a photograph of it. We have a no-swearing policy here at “About Last Night,” which I try to honor when I don’t forget, and one of Liz’s song titles breaks it, so the photo appears after the jump.