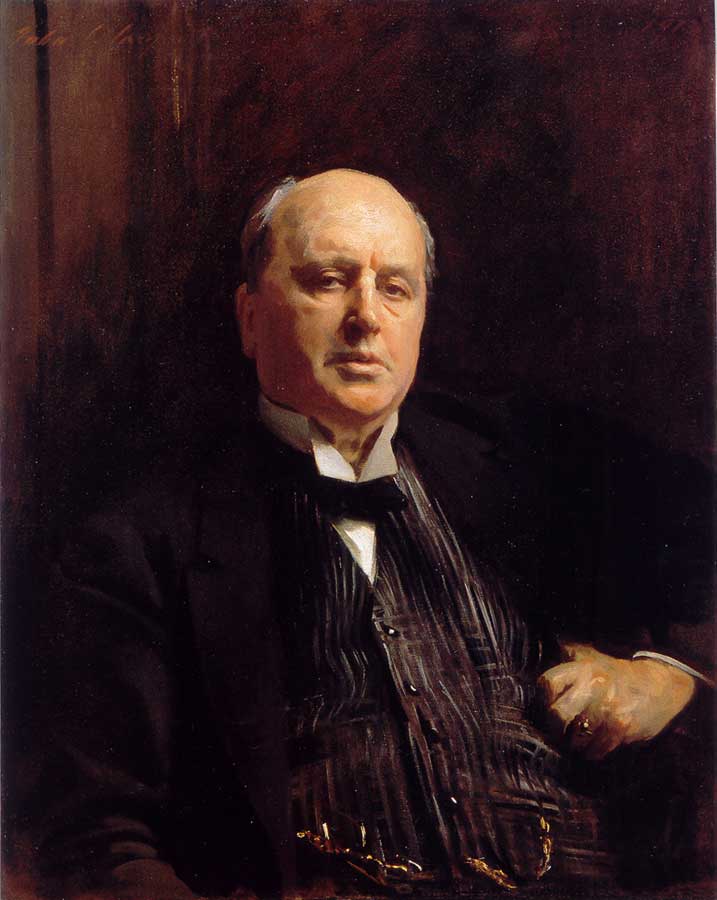

5 x 5 Books … is a recommendation of five books that appears regularly in this space. Today’s installment comes from critic Michael Gorra. A professor of English at Smith College, Gorra is the editor of The Portable Conrad, out this month from Penguin. Earlier this year, he wrote about Henry James in Florence.

You’ve read The Master and maybe Author, Author, you cottoned onto Diane Johnson’s Isabel in Le Divorce, might even have known that great old Beerbohm parody, “The Mote in the Middle Distance.” But James freaks can never quite get enough, and when we get done retelling our favorite anecdotes (most of them cribbed from Edith Wharton’s memoirs) we go looking for his figure in the carpet of other people’s work. We’re so apt to do it, in fact, that there’s even a book about it, Adeline Tintner’s Henry James Legacy: The Afterlife of his Figure and Fiction. Here are five places to find him.

You’ve read The Master and maybe Author, Author, you cottoned onto Diane Johnson’s Isabel in Le Divorce, might even have known that great old Beerbohm parody, “The Mote in the Middle Distance.” But James freaks can never quite get enough, and when we get done retelling our favorite anecdotes (most of them cribbed from Edith Wharton’s memoirs) we go looking for his figure in the carpet of other people’s work. We’re so apt to do it, in fact, that there’s even a book about it, Adeline Tintner’s Henry James Legacy: The Afterlife of his Figure and Fiction. Here are five places to find him.

1. “At The Grave of Henry James” by W.H. Auden. Actually I don’t much like this poem, which dates from just after the poet moved to America at the end of the 30s, that low dishonest decade. It has a creaky start, but it ends well, as it asks for forgiveness for the treason of all clerks; HJ was, at the time, famous as the writer who never served a cause outside his art. The grave itself is easy enough to find–he’s buried with the rest of his family in the Cambridge municipal cemetery, a slightly bedraggled cousin to the better-groomed Mt. Auburn. Auden saw it covered with snow, and my own first visit was on a bitter January day. I had a cold, and I was so hopped up, or maybe down, on antihistamines that I could hardly drive. But it was worth it.

2. The Ghost Writer by Philip Roth. The young Nathan Zuckerman sits up one night in the fifties reading “The Middle Years,” the tale of a dying writer who wishes he had a second chance to make his work come right. Roth must be on his third or fourth chance by now, so many revisionary selves has he put himself through. Or maybe its just Zuckerman. And James got that chance as well, in writing his prefaces and revising his work for the New York edition. What’s especially good about the Roth is the sense it gives of James’ importance to the self-conception of the mid-century American novelist, maybe especially his curious importance to Jewish writers.

3. “Lady Tal” by Vernon Lee. Vernon Lee–as everyone knows–is the pen-name of Violet Paget, an Anglo-Florentine and a childhood friend of John Singer Sargent. She wrote well about Italian art and also produced some genuinely creepy ghost stories. James liked her and admired the depth of her knowledge, but he never forgave her for turning him into a novelist called Jervase Marion–a name he might have used himself! The story is set in Venice, and other characters are recognizable as well. And while it is indeed catty it’s also highly readable, quite funny, and probably accurate in its portrait of his various hesitancies. Easiest to find now in Elaine Showalter’s anthology, Daughters of the Decadence.

4. Edith Wharton, passim. Which is exactly what one isn’t supposed to say these days, except that “Roman Fever” is the best analysis of “Daisy Miller” every written, and The Age of Innocence is all over The Portrait of a Lady. Not just because Wharton’s Newland and James’ Isabel share the same last name, but because Newland has memories of going dancing in Florence with a rather decayed group of expatriates–did the Countess Gemini try to hit on him? Also he’s a member of the Century Club, where if only he were real Newland would in 1875 have met a writer his own age, a young man giving New York one last try before heading off at last to Paris.

5. “Pandora” by–well, by HJ himself. Find this gem in the Library of America edition of his collected stories. A German diplomat comes to America, and on the ship over he both watches an American girl sashay along the deck, and reads a story about the misadventures of another such girl in Switzerland and Rome. Are the real girls like the ones in books, he wonders? Is “Daisy Miller” true? If you like this, you can then pick up W.D. Howells’ lovely Indian Summer, a book set in Italy in which the characters criticize each other for not coming up to the tone that reading James has made them expect. It’s a typically understated joke by the editor who bought The Portrait of a Lady for the Atlantic.

CAAF: 5×5 Books of a New World Order by Calvin Baker

5 x 5 Books … is a recommendation of five books that appears regularly in this space. Today’s installment comes from an old friend of mine, Calvin Baker. Calvin’s the author of three novels, including, most recently, the magnificent Dominion, which Maud championed as one of the best books of 2006.

Whenever a certain kind of person asks me what the world beyond the post-modern looks like I usually reply that it will look like a poem or a film or a sculpture: like art; not theory. But art in America, as a rule is understood in its relationship to other forces (mercantile, political, academic, whatever), never its own primacy. It’s a situation, whatever its other advantages or disadvantages, which has engendered a conversation that has failed to understand the fundamental shift underfoot, concerning itself instead with its own self-reflective anxieties.

The truth, or closer to it, is that the next great thing is already well underway, and it is possible to point to several writers who share a concern, an opening move if not a common project, that might be described (roughly, for now) as creating narratives large enough to contain our fractured inheritances from the last epoch. While some of these writers have already been acclaimed for various aspects of the stories they’ve told, the underlying scale and import of the questions being posed — What’s Going On? — have yet to be taken up in a meaningful way.

In the meantime here are five novels of ideas (3 classic and 2 that seem destined to become canonical), each revolutionary or anti-revolutionary in a way that describes their respective ages as well as anything else. They deserve to be read, or read again, on different terms: in light of their relationship to the novel itself.

1. Buddenbrooks by Thomas Mann. When Tony Buddenbrooks, a beautiful, divorced, woman of dwindling prospects dismisses a wealthy suitor because, “Er sagt mich stadt mir” (He says who <.em>instead of whom), and it’s not the beginning of a morality tale then you know you’re in a world of the sublime. In this case it’s the fluid, intellectually sophisticated, milieu of the early 20th-century haute bourgeoisie (Bildungsburghertum), with the shadow of aristocracy on one hand, and the tenuous nature of their own position on the other.

Mann, of course, was the last European master who could act with the underlying assumption that the intellectual, political and material wants of the society he was born into shared more than physical space — that his project and the values of his culture were one — without drawing suspicion of naïveté or worse.

He continued to believe this until he was living in exile. Claiming until the last that the betrayal of the rest of the society by its political custodians was an aberration. Historians might make other claims, however, as the arcs of the 20th century played out at different paces in the European capitals, the case can still be made for Mann as the last of the great realists, trusting unmediated literary representation and inquiry to make deep sense of the world. Never mind that it was already a modernist one.

2. Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison. Ellison might be the single most important American writer of the last hundred years. Where others traded on well-established schools of thought he combined the protean modernist sensibility of Toomer with the formal perfection of the European novel to create an Erfahrungsroman for the 20th century. He is the fork in the road of American literature, one path leading to the well-behaved world of mannerism and craftsmanship, and the other diving down the rabbit hole into the gleeful madman lands of Reed and, only slightly less directly, Pynchon. Besides having a share to the claim Great American Novel, this book does even more than invent the jazz novel. This is funk before funk had a name.

3. The Alexandria Quartet by Lawrence Durrell. This is the epitome of a book whose failures show as much its triumphs. Durrell lays bear his ambition with the claim: “Modern literature offers us no Unities, so I have turned to science and am trying to complete [a novel] whose form is based on relativity. Three sides of space and one of time. … I have tried to turn the novel through both subjective and objective modes…” Post-modernism avant la letter. And that’s just the hand he reveals. Among a great many other things this is a project that also happens to be Cosmopolitan, devious (Sadian, Lawrencian, that is to say before the pill) and sexy as hell.

If his worldly gaze strikes the contemporary reader as chauvinistic, or as sharing a border of Empire with Kipling, well nothing can transcend its age entirely. Here is a writer whose meridional creativity grasps with a beautiful ease of intelligence the relationship between the fleeting and the permanent in a single sentence. Between the body, language and the fragile invisible they may sometimes express, or summon into being.

4. By Night in Chile by Roberto Bolaño, translated by Chris Andrews. Latin American artists tend to look further afield for inspiration and models than their northern counterparts. Certainly they tend to be more Europe-facing. So much so it might be argued that between the anxieties of whiteness and so-called Magic Realism the following generation had a hard time taking shape. It turns out, in the best of cases, it’s because they were out wrasslin’ with the biggest problems they could find.

For Roberto Bolaño the essential, atlas-like question is the nature of creation and the genesis of evil itself, both its personal and historical manifestations on a global scale. As might be imagined ambition like that needs a language of its own, and Bolaño creates a startling poetry to carry his meaning over.

If Bolaño is one of the great artists of his generation (and his core achievement seems to me on a level with Achebe — Sui generis), he has found in Chris Andrews the ideal translator. Where other interpreters seem to miss a beat, Andrews displays an intensity and lightness that get to the poetic and metaphysical reaches without losing, or attempting to sweep away, the spaces and silences of what cannot be translated.

5. Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro. Post-modernism taken seriously has become the province of the grand old men, playing out the bittersweet end of what was the game of their times. It is not equal to the codes or experiences of our moment. While Coetzee — viewed with mutual suspicion by most black African writers, who suffer a different double-blind — tries to balance the equation while describing magnificently and, in the end quite revealingly, the noble and tortured last wall of the old school, several writers have already scrambled over to the other side. Among the many conceivable solutions none is quite so sly as the one offered by Kazuo Isiguruo (who shares many concerns with Coetzee, but feints to the zeitgeist as often as the canon). His deceptively simple sentences contain whole other worlds, vast unspoken epistemologies, beneath their surface. Among other things Never Let Me Go is a haunting disquisition on whether love or art can explain our world, or save us from inhuman fates.

The most frequent complaint against this book is: Why don’t they make a run for it? Opening onto the larger: Why don’t we all?

CAAF: Morning coffee

• John Updike on wonky dinosaurs. (via Ed.)

• Daniel Engber to Jonah Lehrer: “Proust was not a neuroscientist.” Engber’s article closes with a call for entries for a list of the “all-time worst literary allusions in the history of peer-reviewed science.” The first submission:

“Great writers, from Dante to Joyce, often weave various meanings into their writings.”–Guigo et al. 2006. Unweaving the meanings of messenger RNA sequences. Molecular Cell 23: 150-151.

CAAF: Reconstructing the whole monstrous shape

Lately I’ve been dipping in and out of Louisa May Alcott’s first novel, Moods. The novel was published in 1864 (four years before the publication of Little Women made Alcott famous), and it’s one of a handful of books that she wrote for an adult audience.

The plot deals with a love triangle, and it seems to be commonly accepted that Alcott modeled the novel’s tomboy heroine after herself, and the two men she’s torn between after Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. I don’t why the idea of this love triangle tickles me so, but it does. Infinitely. I only regret there was no sequel in which the heroine, now a contented old married lady, is jarred from her knitting by a knock on the door from Merman Helville, a man of quiet but manly disposition who after decades of sea-voyaging has come home to claim his bride.

The edition I’m reading is a nice one; put out by Rutgers University Press, it contains substantial revisions to the novel made by Alcott years after its initial publication (it was republished in 1882) as well as an early review of Moods written by Henry James. If you’re a writer, I invite you to pause here to imagine what it would be like to have Henry James critique your first novel: To borrow from the language of Moods, an agitated spirit might fill your breast.

I adore Alcott — she’s a great hero of mine, has been since I was a kid (oh Jo!) — so I feel a tinge of disloyalty in finding James’ review wickedly funny. In this excerpt James first supplies some plot synopsis, then takes issue with a type of romantic lead he finds all too common in the work of “lady novelists” (note: the Warwick character is the one based on Thoreau):

The heroine of “Moods” is a fitful, wayward, and withal most amiable young person, named Sylvia. We regret to say that Miss Alcott takes her up in her childhood. We are utterly weary of stories about precocious little girls. In the first place, they are in themselves disagreeable and unprofitable objects of study; and in the second, they are always the precursors of a not less unprofitable middle-aged lover. We admit that, even to the middle-aged, Sylvia must have been a most engaging little person. One of her means of fascination is to disguise herself as a boy and work in the garden with a hoe and wheelbarrow; under which circumstances she is clandestinely watched by one of the heroes, who then and there falls in love with her.

CAAF: To gluttony

We always celebrate Thanksgiving at my parents’ house here in Asheville. My parents are accomplished cooks and hosts, but a while back it struck me that I should make a gesture toward contributing to the meal. I was told to bring “green bean casserole.” This was disappointing — although I often talk about not being a good cook, I was a little offended that my family seemed to believe me. And green bean casserole is, I’ve decided, the cream-of-mushroom equivalent of an O. Henry story: A sacrifice to make, and a sacrifice to eat. But my mom continued to request it, so each year I would arrive at their door clutching a murky, bog-laden Pyrex. Last year, however, circumstances combined to make it impossible for anyone else in the family to cook, and I was put in charge of the dinner. The experience was not unlike when a fourth-string scrub is plucked from the bench for the Big Game. I made beef tenderloin, homemade macaroni and cheese, cranberry chutney and a beautiful pear salad (I was working with the theme: what if the Pilgrims had landed at a Wisconsin steakhouse instead of Plymouth? After dinner we had Grasshoppers.) It wasn’t traditional — I had to make something that could be delivered picnic style — but it came off well enough that this year I’ve been asked to reprise the chutney and salad. No green bean casserole, hoorah.

Tomorrow is also Mr. Tingle’s and my anniversary. It’s our seventh, so we’ve rented The Seven Year Itch to watch when we get home. (I now wish I’d had the presence of mind to rent Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? too, to make it a truly romantic double feature.)

I have many things to be grateful for this year. One of the nicest among them is joining Terry and Laura at About Last Night. My thanks to them and to you readers, along with hopes that you enjoy a happy, safe holiday. See you next week!

CAAF: Parcel post

A couple prize items that arrived in the mail this week:

• The “Fantastic Women” issue of Tin House, which looks wonderful.

• The Letters of Ted Hughes. After mentioning coveting this book a couple weeks ago, I broke down and purchased it from Amazon UK. (I dread my next credit card statement, when my total will have been converted from pounds into euros into dollars. The VAT alone is roughly one hundred million dollars.)

Both of these now sit in the living room, poised to play their part in the eventual book avalanche .

CAAF: Morning coffee

• Michael Gorra’s lovely appreciation of the town libraries of New England includes a “search for a library that doesn’t exist”: the library that appears in Edith Wharton’s novel Summer.

• In an address given at Amherst College, Marilynne Robinson describes long hours spent in the campus’s Frost Library (this was in the years following the publication of Housekeeping):

I was teaching a creative writing class at the time, and then descending to the dim interior of the library to read up on the political thought of Daniel Defoe and Henry Fielding, to slog through Frederick Eden, Thomas Carlyle and the Fabians. During this time I read the first volume of Capital and a number of the books that Marx notes, including England and America, by Edward Wakefield, which prompts the most direct discussion of the United States to occur in Capital (though Marx wrote a great deal elsewhere about America and for American publication). I read Thomas Malthus and Adam Smith. I found and read forgotten writers mentioned by those writers whose work is still invoked by educated people, though, as I learned again and again, it is actually read somewhere between seldom and never.

I was reading my way through what is called the dismal science–no science at all but thoroughly dismal. Its innumerable contributors called it political economy. This immersion of mine was a strange project by any standard, made satisfying by the fact that Frost Library was almost always equal to the demands I made on it. So passed a certain percentage of my relative youth.

Related: DFW votaries may recall mentions of Frost Library in a couple interviews, including Wallace’s appearance on The Charlie Rose Show, where he describes himself as having been “a library weenie from the lower level of Frost Library at Amherst College.”

These notes about Frost interest me because I went to Amherst and still have dreams about the library’s lower levels. These levels are located below ground, and they’re like distinct continents: No natural light, so a land of books and moles and carrel fiefdoms. During my time, at least one floor had mobile shelves (similar to this system but infinitely more ancient and jerry-rigged in appearance) and I used to worry about dying a horrible death trapped between two colliding shelves, which made me highly alert when foraging for any sound that might indicate the shelves were about to move. However, as far as I know, Frost has yet to record a fatality. In the catalog of bibliophiliac-related paranoias, this one belongs next to the fear of death by book avalanche in one’s living room.

CAAF: Bits and pieces

A nice, unintentional pairing last night: The movie version of Young Frankenstein followed by a couple chapters of Alasdair Gray’s Poor Things, a modern Frankenstein tale set in Scotland. (I have the Dalkey edition and, yes, it’s ugly. But still, a wonderful book that you should read!) The rental of Young Frankenstein was at the behest of Mr. Tingle whose been overworking and in need of a little Mel Brooks. This time the bit we latched onto is Cloris Leachman’s revelation about Dr. Frankenstein senior: “Yes, he was my … boyfriend!”

RELATED:

• Terry’s review of the Broadway adaptation of Young Frankenstein in today’s Wall Street Journal.

• NPR story about the show, which Mel Brooks says came about after the line he was my boyfriend got stuck in his brain. I know how you feel, Mel.