“Therefore, if we built splendid castles (phalansteries, perhaps, they might be more fitly called,) and pictured beautiful scenes, among the fervid coals of the hearth around which we were clustering — and if all went to rack with the crumbling embers, and have never since arisen out of the ashes — let us take to ourselves no shame. In my own behalf, I rejoice that I could once think better of the world’s improvability than it deserved. It is a mistake into which men seldom fall twice, in a lifetime; or, if so, the rarer and higher is the nature that can thus magnanimously persist in error.”

Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Blithedale Romance

CAAF: Afternoon coffee

• Francisco Goldman is profiled at The Guardian.

• A wonderful appreciation of Angela Carter in the Los Angeles Times. (Via the Lit Saloon.)

Which gives me an excuse to share an enjoyable, stray nugget from Rick Moody’s essay about Carter in the Fantastic Women issue of Tin House: “… when I once admitted that I’d written one story while on Quaaludes, Angela said, ‘Ah, Quaaludes, the aardvark of the drug world.'”

CAAF: From the Dept. of It’s Easier to View Art as a Gift When You Don’t Have Bills to Pay

The drama surrounding the Willesden Herald Short Story Prize continues. A few days after the contest’s judge, Zadie Smith, announced that no prize would be given, one of the contest’s panel of short-listing judges has stepped forward to explain what happened behind the scenes with the judging process leading up to the decision. (Via Ed.)

A friend of mine was fatigued at “hello” by all this, saying, “I can already imagine the newspaper articles mocking Smith, Smith’s injured reaction, the debates on the blogs…” but I remain riveted. In her decision to abstain from awarding the prize, Smith has elected to act as the voice of conscience; these aren’t her words, but her position seems to be, in essence, “None of these stories are good enough, and I won’t assign my name to anything second-rate. And I think we should all try harder to write and read well.” Which is admirable, but then she is also — as a tremendously successful, feted author — able to exercise conscience in a way most others are not. Most of us live in a world of accommodation and make-do, but Smith doesn’t have to; her talent and success have earned her a rank above that kind of shifting. She can make a stand for truth & beauty, and it won’t hurt her book sales, or her ability to be considered for major prizes, or get reviewing gigs — or any of the other considerations that a more mid-list author might have to make, and which would most likely end with him or her going with the flow and awarding the prize to whatever entry they deemed best.

And then here’s poor Bilal Ghafoor, who is not at the top of the food chain, and so must write a beleaguered editorial explaining all the accommodations he and his fellow selection panelists have been forced to make. Read his note and there’s some talk of truth and beauty in there, but mixed in with it are sad tales of data entry, crowded dining room tables, neglected families, logistics juggling, and cups of tea drunk: “We stayed up all night! We spent hours, hours!”

My interest in this is probably all out of proportion, but the entire situation seems to encapsulate some larger struggle about idealism versus accommodation in art. I keep thinking of Thoreau and Shelley, both agitators for purity and of throwing off the yoke of the status quo, and how they were both sons of gentlemen, and so, by inheritance, free from the everyday concerns that make compromisers of the rest of us. (Shelley especially was a great spinner of utopias on other people’s dollars, with no provision for who — once utopia was achieved — would clean up there. You get the sense that Thoreau at least would do his own dishes.) Similarly, part of my long interest in Louisa May Alcott has to do with how she seems an embodiment of this struggle between exaltation and the quotidian: The daughter of a respected philosopher holed away in her room writing Gothic potboilers to support her family, because her father’s high-flown, wildly impractical thought experiments had bankrupted them.

Which isn’t to say I think Smith was wrong to act on principle (especially not having read the shortlisted stories myself, which, for all I know, were real dogs). Only that I find myself feeling for both ends of the equation: On the one side you have a great artist sounding the call for us all to pursue loftier goals, and on the other you have the quite natural irritation of people who, hearing such a call from on high, just want to say “Piss off.”

CAAF: The murkiest bloodlines since the House of Plantagenet

A while back I realized I’d bought several novels simply because their jacket copy invoked Nabokov in some shape or form, e.g., “reads like a crazy love child of Nabokov and Gogol” or “prose so dazzling you’ll feel like Nabokov walks among us again.”

A while back I realized I’d bought several novels simply because their jacket copy invoked Nabokov in some shape or form, e.g., “reads like a crazy love child of Nabokov and Gogol” or “prose so dazzling you’ll feel like Nabokov walks among us again.”

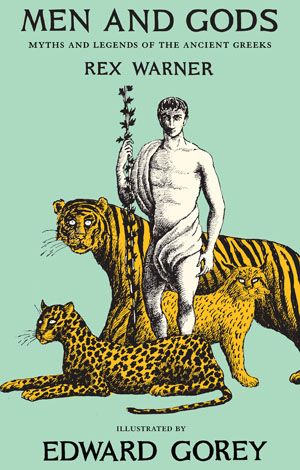

It turns out I’ll also buy anything that says “Illustrated by Edward Gorey” on the cover. Most recent example: Men and Gods, which NYRB just put out. It’s a beautiful little book; it’s a small hardcover and the whole presentation — size, type style, the mint color of the cover — is pleasingly reminiscent of old middle-school library books. (I can’t help but think what a nice Valentine’s Day present it would make.)

I’ve been reading a lot of Greek mythology lately, and with the more in-depth books – meaning here anything more difficult than D’Aulaires — I’m finding certain bits hard-going before bed. Here is a typical passage from Warner, with a track of my comprehension:

Jason knew the story of Phrixus, since he had been told this and other stories of gods and heroes by the centaur Chiron. [We’re good.] He also knew that Phrixus had been related to him, since his own grandfather had been the brother of Athamas, who in the end had been driven mad by Juno [Still good.], but who had had by his first wife, Nephele, two children who were called Phrixus and Helle. [Faltering but still following.] Later Athamas had married Cadmus’s daughter Ino [and I’m out.]…

I blame my mother for not making me read the Bible more as a child.

CAAF: Write up, not down

Last week, David Itzkoff started off a review in the NYT Book Review by observing, “I sometimes wonder how any self-respecting author of speculative fiction can find fulfillment in writing novels for young readers.” It’s a maddening lead, especially for people who write and love young adult literature. Neil Gaiman, whose novel InterWorld was one of the two YA books covered in Itzkoff’s review, responded in a puzzled way on his blog, noting, “I think that rule number one for book reviewers should probably be Don’t Spend The First Paragraph Slagging Off The Genre.” And at Crooked House, Stephany also provides an eloquent response.

I like what Stephany writes so much I’d like to print it here except that wouldn’t leave me room to share this lovely, sensible thing E.B. White said in his Paris Review interview that seems apropos:

Interviewer: Is there any shifting of gears in writing such children’s books as Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little? Do you write to a particular age group?

White: Anybody who shifts gears when he writes for children is likely to wind up stripping his gears. But I don’t want to evade your question. There is a difference between writing for children and for adults. I am lucky, though, as I seldom seem to have my audience in mind when I am at work. It is as though they didn’t exist.

Anyone who writes down to children is simply wasting his time. You have to write up, not down. Children are demanding. They are the most attentive, curious, eager, observant, sensitive, quick, and generally congenial readers on earth. They accept almost without questions, anything you present them with, as long as it is presented honestly, fearlessly, and clearly. I handed them, against the advice of experts, a mouse-boy, and they accepted it without a quiver. In Charlotte’s Web, I gave them a literate spider, and they took that.

Some writers for children deliberately avoid using words they think a child doesn’t know. This emasculates the prose and, I suspect, bores the reader. Children are game for anything. I throw them hard words, and they backhand them over the net. They love words that give them a hard time, provided they are in a context that absorbs their attention. I’m lucky again: my own vocabulary is small, compared to most writers, and I tend to use the short words. So it’s no problem for me to write for children. We have a lot in common.

I read White’s interview last year — shortly after Terry mentioned his enduring affection for Stuart Little — and that part’s stayed with me.

CAAF: Afternoon coffee

• Zadie Smith explains why no prize will be given this year in the Willesden Herald‘s short story contest. Really provocative & interesting. (Via TEV.)

• The affair of the mind that may have inspired Possession. (See also.)

CAAF: Hindsight

Over at McSweeney’s, great authors predict the outcome of the Super Bowl. The conceit’s solid, and there’s a good Raymond Carver/Gordon Lish joke in there, but the parody of Jane Austen is irritatingly off:

Hyacinth and amethyst adorned the landscape of her heart, betrothed to fragrant oakmoss and blazing scarlet within the amorous lovestrokes of an incandescent horizon. In the shade of the gray branches, she put pen to paper. “I love you, Tom Brady,” it began. “Though others call you wicked.”

Prediction: Handsome Tom 46, Stern Aunt Louisa 9

So much wrong, including that Austen would have been Giants all the way.

I missed last night’s installment of PBS’s Complete Jane Austen, Miss Austen Regrets due to the Super Bowl. The game was exhilarating but, unlike the Austen, could boast only one neat costume: Belicheck’s fancy red sweatshirt. Did anyone see it (the Jane Austen, not the Super Bowl)? I admit as the series continues week after week what I’ve become most interested in is the cleavage of the actresses, which — not to be vulgar or prudish, but strictly anatomical — are undergoing some extraordinary effects that underwire alone can’t explain. In Mansfield Park, poor “plain” Fanny and her cousin Maria had the most opulent displays of decolletage to appear on my TV screen since Madonna stopped by the Golden Globes after giving birth to Lourdes. And then, if I remember right, Jennifer Ehle’s bosom in the Colin Firth edition of Pride and Prejudice, which begins re-airing this next Sunday, is located about four inches north of where you might expect it to be. It’s all so mysterious.

CAAF: Their struggle punctuated by cries

Buried in this Financial Times profile of critic James Wood is some interesting backstage stuff about the New Yorker‘s editing process:

At The New Yorker, whose sacerdotal approach to editing and mania for accuracy were derided in the 1960s by Tom Wolfe for leaving readers lost in “whichy thickets”, Wood has now found himself at the fastidious end of the publishing scale, which on the whole is a good thing. As with The New Republic, the editing process is one where he is constantly being asked to go deeper. “I find it isn’t the editors who put that qualification in,” he says, “it’s the fact-checkers. They have to be resisted, because they want to water down unprovable assertions. So you say: ‘There is great disagreement about Cormac McCarthy’s status’ – this was a piece I wrote a couple of years ago when No Country For Old Men came out – and they’ll say to you: ‘Well, I’ve been on the internet and I haven’t found much disagreement actually.’ So you say: ‘Well, for instance, Ian McEwan thinks he’s complete shit.’ ‘Yeah, but we’ll have to say then there’s been “some” disagreement.’ And already it’s getting wimpish.”

His only other peeve is the way the magazine treats the semi-colon. “The New Yorker will try as often as possible to change it into a colon,” he says – ascribing it to an attempt to mimic English properness. “I love semi-colons,” he says with all the enthusiasm of a 10-year-old talking about chocolate.

Otherwise the profile reveals little you didn’t already know or suspect, forcing one to conclude that the lives of amiable, bookish men devoted to their families and the life of the mind don’t make for the most colorful copy. I was thinking it was a shame the reporter couldn’t borrow biographical details from actor James Woods’s life to punch things up — The critic was dismayed when he arrived at the Guardian one morning to find a disfigured doll had been left on his desk. — but the colon/semi-colon skirmishes will have to do. (Via.)