I miss Hilary and, I expect, always will. I gather that’s what happens when you lose a partner in the heartbreakingly unexpected way I did. Just the other day I muttered to myself, “Darling, I can’t remember—did you go to that Skin of Our Teeth with me in Stockbridge last July, or were you feeling too sick?” Silence. “Oh,” I said, then sighed deeply.

In recent days, though, my strongest emotion has not been grief but homesickness. It’s been more than a year since I last saw my family, and while I was too preoccupied wth Hilary’s final illness and untimely death to think much about them during the first half of 2020, they are now constantly on my mind, as is Smalltown, U.S.A., the tiny home town in southeast Missouri that I love so much.

It was our custom to spend Thanksgiving with Hilary’s family in Connecticut and Christmas with my family in Smalltown, but the latter tradition came to an end after my mother died in 2012. After that, my visits to Smalltown grew increasingly sporadic, and I no longer went there for the holidays. It had become challenging for Hilary to travel by air, and we both felt that her declining energy, such as it was, would be best spent getting her to and from Florida’s Sanibel Island, her favorite place in the world and one whose comfortable winter climate was well suited to the needs of a middle-aged person with chronic respiratory disease.

We planned to spend Christmas of 2017 on Sanibel, but Hilary was too sick to travel, so we stayed home instead. In 2018 she celebrated Thanksgiving in the hospital in Connecticut, where I brought her a full-scale dinner from the best restaurant in town. She cleaned her plate with delight, not knowing that it would be her last Thanksgiving dinner: a year later, she was unable to do much more than pick at food.

By then I’d mostly stopped traveling by air, fearing that Hilary’s condition might worsen without warning and wanting to be nearby in case of an emergency. In July of 2019, though, she urged me to take one more trip to Chicago and Smalltown while I still could, and so I did. That was the last time I saw my hometown and my family. It was, as I wrote shortly after returning to New York, a glorious visit:

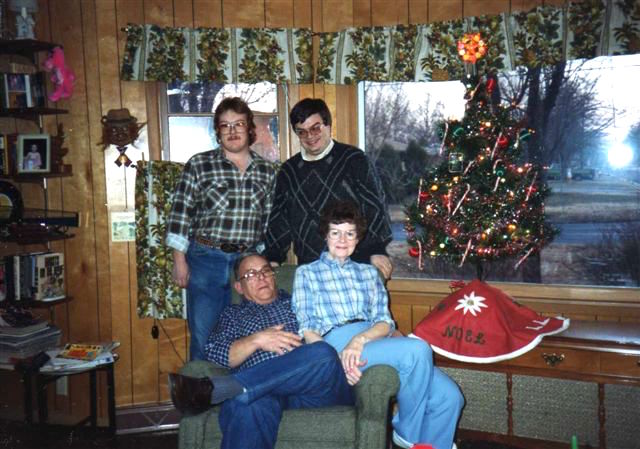

I contrived to pack a whole string of soul-satisfying events into a three-night stay. Most of them, to be sure, were the same homely things I always do when I go to Smalltown: I drove around town, visited my parents’ grave, and breakfasted on biscuits and gravy at Jay’s Krispy Fried Chicken. I’d made a special point of asking my brother to cook out, so he smoked huge chunks of ribeye steak on which the three of us dined one evening. I’ve never eaten a tastier piece of meat, though I would have been just as glad to eat ham sandwiches with David and Kathy, sitting at the kitchen table and catching up on the commonplace things that James Agee’s people chat about in the after-dinner gathering that he describes so lovingly in A Death in the Family: The talk is quiet, of nothing in particular, of nothing at all in particular, of nothing at all. The point of such talk is the talking itself, an act of secular communion that tightens the myriad ties of memory that bind a close-knit family.

Hilary grew much sicker very soon thereafter, and I never again left her side save to review shows in New York and run essential errands. At some point after she died in March, I briefly gave thought to flying out to Smalltown, but by then the ravages of the pandemic had made air travel unsafe, and I never even considered going there for Thanksgiving or Christmas, just as I decided to postpone for a year flying to Sanibel Island to scatter Hilary’s ashes on the beach. My roomie and I are mostly locked down in upper Manhattan now, and I don’t expect to hit the road again, whether for work or pleasure, until a COVID vaccine becomes available.

I long passionately for that day to come. I talk to David and Kathy on the phone every couple of weeks, which is absolutely better than nothing but not nearly as good as seeing them in Smalltown. Just the other day I looked at the online menu of Lambert’s Café, the throwed-rolls restaurant that is my home town’s main claim to fame, and fantasized about what I’d order the next time the three of us ate there. I read the Smalltown Standard-Democrat on line most days and check out the local news. Just last week I ordered a bottle of Durkee Famous Sauce, my father’s favorite sandwich spread, which I hadn’t tasted for a quarter-century, and was overjoyed to discover that it tastes as good as ever.

Would that I could spread it on sandwiches made out of leftover Thanksgiving turkey, but my roomie is a vegetarian. Fortunately, she picked up a pumpkin pie on Saturday, and I ordered a box of Stove Top Stuffing from the neighborhood grocery store (we get everything delivered now). I’ll serve it to myself on Thursday, accompanied by a toasted smoked-turkey sandwich slathered with Durkee Famous Sauce and some sort of cranberry dish prepared by my roomie, who is a very good cook.

As I eat, I will try my best to give honest, heartfelt thanks for the blessing of the fifteen gloriously happy, largely unshadowed years that I spent with my beloved Hilary before her health started at last to fail—as well as for David, Kathy, and Smalltown, U.S.A. I long with all my heart to see them, and though it will likely take a while, I know a time will come when I spend Thanksgiving in Smalltown once again and remember how very, very lucky I am.

* * *

Dave Frishberg sings his own “The Difficult Season”: