“Friendship needs a certain parallelism of life, a community of thought, a rivalry of aim.”

Henry Adams, The Education of Henry Adams

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

“Friendship needs a certain parallelism of life, a community of thought, a rivalry of aim.”

Henry Adams, The Education of Henry Adams

“How can you have confidence in a woman who will not risk entrusting her whole life to you, day and night?”

Cesare Pavese, This Business of Living

Carl Reiner is the guest on This Is Your Life. This episode, hostead by Ralph Edwards, was originally telecast by NBC on March 23, 1960:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“We are born helpless. As soon as we are fully conscious we discover loneliness. We need others physically, emotionally, intellectually; we need them if we are to know anything, even ourselves.”

C.S. Lewis, The Four Loves

From 2007:

Read the whole thing here.Six months ago, I bought a Fairfield Porter lithograph. Two weeks ago, I stood at the edge of a rocky cove near the southern tip of a remote island off the coast of Maine, looking at the same scene Porter viewed when he sketched “Isle au Haut.” To get there, I hiked for two sweaty hours along a narrow woodland trail, stepping over snakes and trying not to turn an ankle….

“The safest road to Hell is the gradual one—the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts.”

C.S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters

I wrote a review-essay for Saturday’s Wall Street Journal book section occasioned by the publication of Straighten Up and Fly Right, Will Friedwald’s important new biography of Nat King Cole. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Walk into any Starbucks in America and listen to the canned music. If the first thing you hear is a standard from the ’30s or ’40s, it’s likely that the vocalist will be Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald or Nat King Cole, the three common denominators of pre-rock pop singing—and a trio of artists who have little in common beyond their posthumous ubiquity. Sinatra was a singer-actor, by turns breezy and despairing; Fitzgerald was the world’s kid sister, a bred-in-the-bone jazzer who sang with a smile on her face and in her voice. As for Cole, his warm, close-grained baritone was as persuasive on romantic ballads as it was on swing tunes. What set him apart from Sinatra and Fitzgerald, though, was the other rabbit in his musical hat: Cole was also one of the half-dozen finest pianists in the history of jazz, a peer of Earl Hines, Art Tatum, Bud Powell and Bill Evans. Even after he disbanded the King Cole Trio, his hugely successful combo, to concentrate on stand-up singing in 1951, he continued to feature his playing in small but tasty doses on record, in concert and on TV.

Cole’s switch-hitting is all but unique. Save for Louis Armstrong, he is the only major jazz musician to have been equally distinguished and influential both as a singer andas an instrumentalist. Yet his youthful career as a pianist is no longer well remembered, and he is now mostly thought of as a pop singer, one of the most famous of the 20th century. In a time when much of the U.S. was still segregated, Cole’s appeal vaulted across racial lines, though racism was always an ugly, sometimes dangerous fact of his life….

* * *

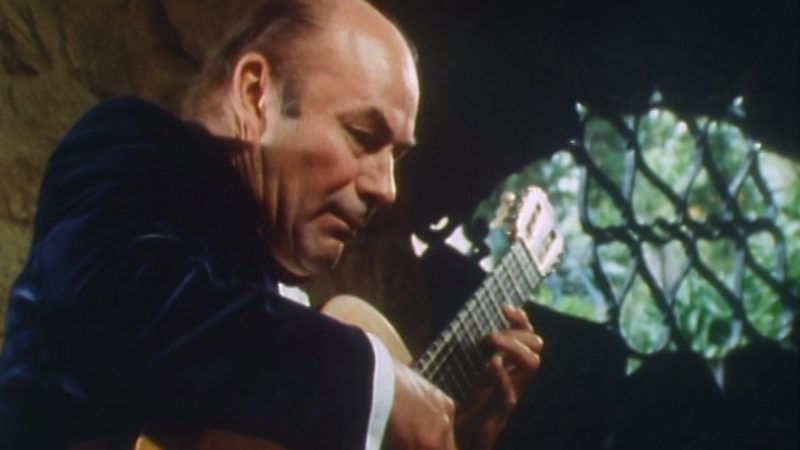

Read the whole thing here.Immediately after I heard of the death of Julian Bream last Friday morning, I wrote an obituary about him that appeared on The Wall Street Journal’s website later that day. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

It’s a safe bet that Julian Bream, who died on Friday at 87, would be remembered if he’d never done anything but play guitar. After Andrés Segovia, he was the best-known classical guitarist of the 20th century, a player of limitless sensitivity who could hold an audience spellbound simply by plucking a few quiet notes on his unamplified instrument—but who also tossed off more technically demanding pieces with the panache of an old-time barnstorming virtuoso.

Yet Mr. Bream did much more than merely play guitar. He doubled on the lute, the guitar’s ancestor, and was responsible in large part for the postwar revival of interest in that long-forgotten instrument. He led his own ensemble, the Julian Bream Consort, one of the first period-instrument groups, and appeared frequently in recital with the tenor Peter Pears, a professional relationship that was immensely valuable to him. “I learnt a lot from Peter about phrasing like a singer, which is what we all try to do on instruments,” he told an interviewer in 2007.

Most important of all, Mr. Bream commissioned and gave the premieres of solo pieces and concertos for guitar by many of the leading composers of his time, among them Malcolm Arnold, Lennox Berkeley, Hans Werner Henze, Toru Takemitsu, Michael Tippett and William Walton. Unlike Segovia, who disliked all but the most conservative 20th-century music, Mr. Bream did more than anyone else to modernize his instrument’s dusty repertoire….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.An ArtsJournal Blog