In order to divert those of you who, like me, are sticking close to home these days, I’ve been posting images of some of the prints and paintings that hang on the walls of the Manhattan apartment that I shared for many years with my late wife Hilary—the “Teachout Museum,” as a friend calls it.

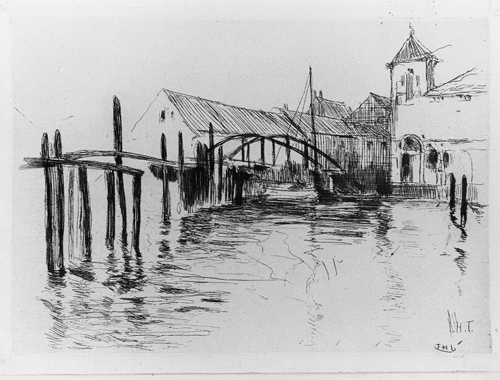

Twachtman’s paintings, alas, are far beyond my means, but he was also superbly accomplished at etching, and his efforts in that medium remain affordable, if rather less so than when I first started collecting. “Dock at Newport” was the second work of art that I purchased, all the way back in 2003, and if memory serves, I bought it from a print dealer for a modest three-figure sum. That surprises me now, since “Dock at Newport” exists in only thirty lifetime impressions and has always been regarded by critics as one of his very finest etchings. It was, for instance, singled out for extended mention in what appears to have been the first review of Twachtman’s etchings, written by Margery Austen Ryerson and published in Art in America in 1920, eighteen years after the artist’s death:

The “Dock at Newport” is full of the delicate evanescent light effects that he loved….We see here too his sense of rhythm. He plays or he gently dances his values. It is darkest just where it makes the print more beautiful to have it darkest and it grows lighter just where it will bring all into a harmony. We notice the same fine sense of gray in this work that is in his paintings of snow and water and mist.

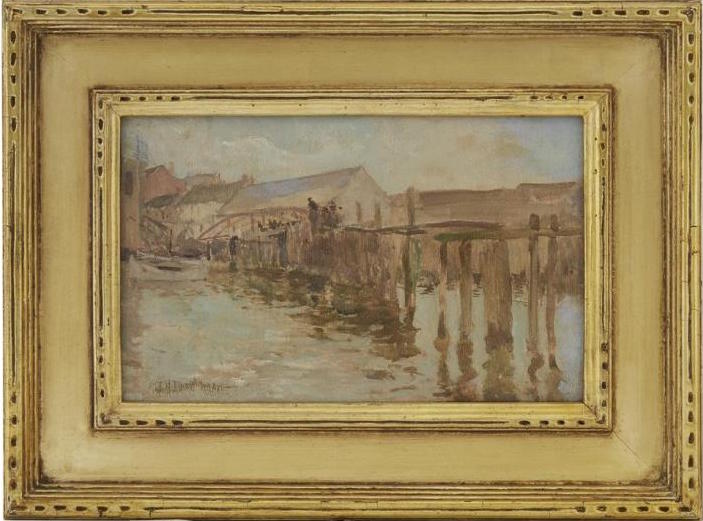

Like many noteworthy prints, “Dock at Newport” is based on a preexisting painting, “The Landing, Newport,” which was done in 1889. It’s not as good as the later etching, which probably explains why it remains in private hands to this day: Twachtman was still working out his mature style, in which French and Japanese influences clearly played a part but which was nonetheless entirely his own. His twenty-nine etchings, of which “Dock at Newport” was his last, are more clear-cut than his later paintings, a few of which teeter on the edge of abstraction, but they are no less individual, and you can see from looking at the earlier painting how he had become himself by the time he created “Dock at Newport.”

“Dock at Newport” hangs in the passageway that leads from the dining room to the kitchen of my apartment in Manhattan, where it keeps company with a watercolor by Jane Wilson and prints by Childe Hassam, Alex Katz, Louis Lozowick, and John Marin. I look at it every day, as I have ever since I acquired it seventeen years ago. It is a little masterpiece at whose simple, almost spare elegance I never fail to marvel, and now that I no longer have a companion with whom to share it, I find a measure of consolation in its timeless beauty.