“So he passed over, and all the trumpets sounded for him on the other side.”

John Bunyan, The Pilgrim’s Progress

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

“So he passed over, and all the trumpets sounded for him on the other side.”

John Bunyan, The Pilgrim’s Progress

Jack Mangan interviews Tennessee Williams on board the S.S. Queen Mary. This clip was originally telecast in 1950 by WJZ-TV as part of Ship’s Reporter, a TV series in which Mangan interviewed celebrities returning from abroad:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

Thomas Campbell, “Hallowed Ground”

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, I consider Robert Benchley’s work as a drama critic. Here’a an excerpt.

* * *

Few things are so fleeting as the fame of a professional humorist. In the ’20s and ’30s, Robert Benchley was one of America’s best-known comic writers, a founder of the Algonquin Round Table who published essay collections with facetious titles like “My Ten Years in a Quandary, and How They Grew” that made him at least as popular as James Thurber. Indeed, a few of his one-liners (“In America there are two classes of travel—first class, and with children”) remain in circulation to this day. But he was also a neurotic self-doubter with a deadly taste for booze, and therein lay his downfall: When Hollywood discovered that he could play his amiably fuddled self on screen, first in comic shorts like the Oscar-winning “How to Sleep” (1935) and then in well-paid supporting roles in such feature films as Alfred Hitchcock’s “Foreign Correspondent” (1940) and Fred Astaire’s “The Sky’s the Limit” (1943), he stopped writing, started drinking in self-devastating earnest, and died of cirrhosis of the liver in 1945. Today Benchley is remembered almost entirely for his films, and his essays are largely forgotten.

Even less well remembered is that from 1920 to 1940, Benchley simultaneously held down a day job as a working drama critic, first for the old Life magazine in its pre-Luce incarnation and then, from 1929 to 1940, as the regular drama critic of the New Yorker. Nor was there anything facetious about his reviews: Benchley covered the Broadway premieres of everything from fluffy musicals to the tragedies of Eugene O’Neill….

What is far from surprising is that when Benchley wrote about light comedy, he did so both amusingly and with perfect taste, distinguishing only between the brilliant and brainless. He loved the early stage appearances of the Marx Brothers (“We may be doing them a disservice by boiling over about them like this, but we can’t help it if we feel it, can we?”). He went like a laser-guided drone to the money moment in “Girl Crazy”: “George Gershwin has written some good numbers, and Ira, his brother, has fitted some excellent words to them, and a young lady named Ethel Merman does wonder with three of them, sustaining one splendid note in ‘I Got Rhythm’ over a period of time usually allotted to the trumpets in orchestration.” Bull’s-eye!…

* * *

Read the whole thing here“How to Sleep,” written by and starring Robert Benchley and directed by Nick Grinde:

From 2010:

Read the whole thing here.If you need to adjust your attitude–and I did–a repeat viewing of Groundhog Day will likely do the trick. I laughed and laughed, then found myself overcome with gratitude at film’s end. I’m the luckiest person I know, and sometimes I forget it. Not tonight, though….

William Shakespeare, Macbeth

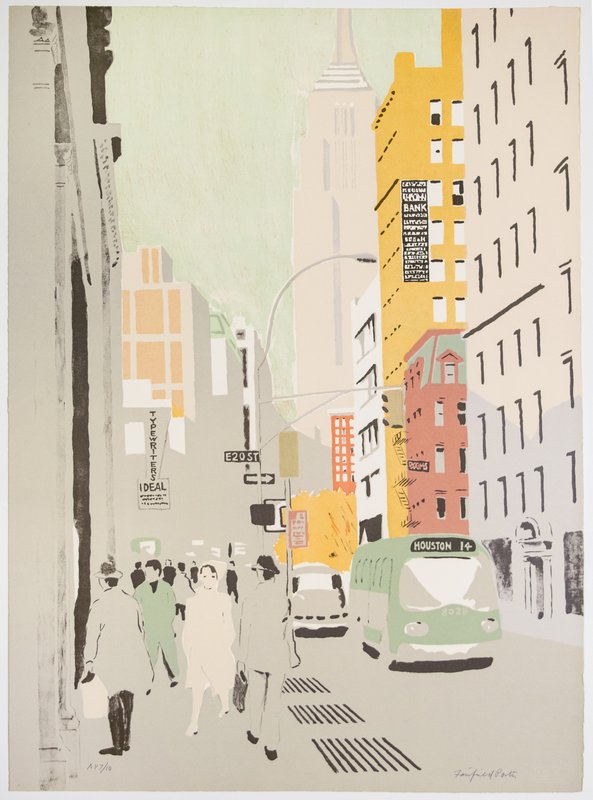

In order to divert those of you who, like me, are staying home these days, I’ve been posting images of some of the prints and paintings that hang on the walls of the Manhattan apartment that I shared for many years with my late wife Hilary—the “Teachout Museum,” as a friend calls it. My latest image is of Broadway, a six-color lithograph made in 1972 by Fairfield Porter, one of America’s most underappreciated visual artists, who was identically accomplished as a critic.

While Porter isn’t exactly a household name, many connoisseurs consider him one of the greatest American artists (and art critics) of the twentieth century, an astonishingly original representational painter whose style fuses two seemingly disparate idioms: the intimate domestic realism of Bonnard and Vuillard and the excitingly free brushwork of Willem de Kooning and the other abstract expressionists.

It was in both of his twin capacities that Porter first opened my eyes to the visual arts, as I wrote in an essay about the origins of my art collection. I discovered his work on a 1995 visit to Kansas City:I went to the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, where I saw a 1960 painting by Fairfield Porter called Wheat.It is deceptively simple—a bluish-gray rectangle of open sky and a smaller rectangle of tan-colored wheat, separated by a farmhouse, three trees, and a barn.

Though Wheat is one of Porter’s best paintings, there is nothing obviously prepossessing about its uncomplicated composition. But something about Wheat struck me with the force of revelation. Was it the way in which the artist freely yet evocatively portrayed a landscape as familiar to me as the house in which I had grown up? Whatever the reason, it spoke to me as had no other painting, and I went straight to the museum shop to find out more about the man who made it.

The shop had no books about Porter in stock. Instead, I found Art in Its Own Terms: Selected Criticism, 1935-1975,a paperback volume of Porter’s art reviews. By a stroke of luck, I had been awakened to the pleasures of painting by one of the finest artist-critics of the 20th century, a major American painter who wrote about art with the same distinction that the composer Virgil Thomson brought to his writing about music. Like Thomson, Porter had a plain-spoken, no-nonsense style that emphasized description over theorizing—“criticism,” he wrote, “should tell you what is there”—and his thoughtful words helped me make sense of the transforming experience I had undergone. As I read what he had to say about painting and painters, I became excited about art—really excited—for the first time in my life.

Like so many of his other prints, Broadway is closely related to a painting by Porter, Broadway South of Union Square. As always, the planes, contours, and color scheme of the painting have been simplfied to arresting effect, and the results remind me of something that Porter said in one of his essays, a remark that I have often had occasion to quote in this space and elsewhere: “When I paint, I think that what would satisfy me is to express what Bonnard said Renoir told him: ‘Make everything more beautiful.’”

In this case, however, the lithograph actually came before the painting, which was completed in 1975, the last year of Porter’s life. I have no idea why this was so, and since the painting is in a private collection, I can only judge its quality at a remove. Nevertheless, I have a feeling that I would still prefer Broadway to Broadway South of Union Square if I were to see them hanging side by side, for there was something about the necessary simplifications of the lithographic medium that brought out the very best in Porter as his life drew to a close.

I first came across Broadway when I was searching for an appropriately American image to put on the cover of A Terry Teachout Reader, whose essays all deal with various aspects of American art. I loved it at first sight, as did my editor at Yale University Press, who replied, “It’s elegant, classy, and a bit nostalgic without the treacle.” I decided to acquire a copy of Broadway after my book came out in 2002, and found one on sale a few months later. It has since been prominently displayed in the two New York apartments that I shared with my beloved Hilary, an exquisite work of art that is also a symbol of my own work as a critic and creative artist who has a powerful attachment to American modernism.Now that the streets of Manhattan have been emptied by illness and fear, I look each day at the crowded, bustling sidewalks of Broadway and remember with heartache and longing what once was—and will once again be.

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

An ArtsJournal Blog