As I watched Dolemite Is My Name on Netflix the other day, I realized that I never anticipated living to see the end of movies as a public and collective viewing experience. Yet it’s well on the way to happening: Dolemite, like The Highwaymen and The Irishman, was made for and released on streaming video, as are a fast-growing proportion of non-franchise movies aimed at adult audiences. Indeed, a full year has gone by since I last saw a new feature film, They Shall Not Grow Old, in a theater.

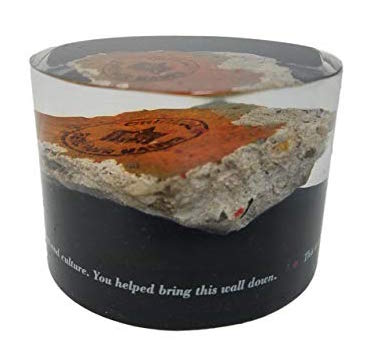

This led me to ask: what other things did I fail to envision taking place in my lifetime? Among the biggest ones was the fall of the Berlin Wall, of which I now own a small piece embedded in Lucite. I use it as a paperweight, and every time I look at it, I’m reminded of the limits of human imagination.Here are a few others, some public and others deeply personal:

• The mainstreaming of “foreign food” in American culture. When I was growing up in Smalltown, U.S.A., you ordered steak, fish, or chicken in restaurants. The first time I ate Italian food (not counting pizza and spaghetti) in a restaurant, it struck me as unimaginably exotic. Today it’s a routine part of my diet, just as few months go by when I don’t have occasion to eat Chinese, Japanese, Thai, or Mexican food, to name only a handful of culinary possibilities. Yes, I live in New York City, but nowadays such cuisines are readily available from coast to coast.

• Smartphones. The cartoons and comic strips of my childhood were full of technological prophecies that have yet to come to pass—but not so Dick Tracy’s celebrated “two-way wrist radio,” which has long since been outstripped by reality. For better or worse? I increasingly think the latter, but it doesn’t matter: we are all plugged in now.

• My sixtieth birthday. I’d imagined turning fifty—pretty much everyone does, unless they have reason not to—but the arrival of my sixtieth birthday, by contrast, came as something of a surprise. When it finally rolled around, I celebrated by preparing to make my professional debut as a stage director, which is a good way to obscure the otherwise painfully obvious fact that you’ll never see fifty again.• The death of my parents. Even though I knew better deep down inside, I still thought they’d live forever, and when I finally lost them both, I knew my world would never be the same. Nor has it been. Not a day goes by that my brother and I don’t remember them with infinite tenderness.

Here’s something I wrote six years ago:

I wonder if either of them guessed how often I’d think about them after they were gone. Not surprisingly, I did so when my first play opened in New York, knowing that the occasion would have meant the world to them. But it’s the routine occasions, not the special ones, that mean the most to me. I think of my mother, for instance, whenever I take a cab down to the theater district to see a show, that being the time when I usually called her–as I did most days–to chat about whatever might be on our minds. I think of my father, by contrast, whenever I happen to see Perry Mason on TV, for he loved nothing more than to guess who did it midway through each episode, if not sooner. (He usually got it right, too.)

I still do.