(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“I often tell myself now—Stravinsky has no other notes, or no more notes to work with, than I have, or anybody else. We all have to choose between the same ones. So the important thing is the exercise of choice.”

Lennox Berkeley, letter to Nadia Boulanger, October 26, 1949

* * *

Not so long ago, Glenda Jackson’s “King Lear” would have come as a surprise. Now it feels like an inevitability. Gender-blind Shakespeare productions border of late on the commonplace—I first saw one, Oregon Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar,” back in 2011—and Ms. Jackson had already played the title role of “King Lear” two years ago in a different production at London’s Old Vic. The real surprise about this “Lear,” directed by Sam Gold, is that it is running on Broadway, where Shakespeare’s darkest, most disturbing tragedy has been produced only twice in the past six decades, in 1968 with Lee J. Cobb and in 2004 with Christopher Plummer. Today, though, “Lear” is well on the way to becoming one of Shakespeare’s most popular plays, so much so that this is actually the sixteenth “Lear” I’ve reviewed in this space (Mr. Plummer’s was the first).

The big question, then, is not “Is Ms. Jackson’s ‘Lear” news?” but “Is it good?” The answer, in a word, is…mostly. It’s a mixed bag, but the best parts, of which there are many, will sear themselves into your memory like mental pictures of an unimaginable disaster—which is, after all, what “King Lear” is—while the unsatisfying aspects of Mr. Gold’s staging are never less than tolerable.

If you had the good luck to see Ms. Jackson in last season’s Broadway revival of Edward Albee’s “Three Tall Women,” in which she played a rich, senile matriarch, then you won’t be altogether surprised by her approach to “King Lear.” As has been the case with many previous Lears, it takes her a while to get up to speed. Ms. Jackson’s harsh baritone voice has no top, which flattens out the poetry of the first part of the play, and her physical slightness—she is the shortest person in the cast and looks rather like an androgynous marionette—puts her at something of a visual disadvantage. Yet there is nothing slight about her imperious manner, and once the storm blows away her illusions and she declines into self-protective madness, she comes decisively into her own….

Ms. Jackson is not, however, the only member of the cast who is giving a performance on the highest possible level. Indeed, Jayne Houdyshell is so remarkable as the Earl of Gloucester that there are moments when it’s tempting to call her the star of the show. Ms. Houdyshell is a great actor who is usually cast in smallish, quirky parts—this is the first classical role in which I’ve ever seen her—and it is thrilling to watch her expand to fill the space occupied by Gloucester, speaking Shakespeare’s verse with a luminous clarity of which I’d never suspected her to be capable….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.* * *

Rarely has a new play by a modestly well-known writer been greeted with such lockstep enthusiasm as has Heidi Schreck’s “What the Constitution Means to Me.” The off-Broadway run having received universally favorable reviews, Ms. Schreck’s play has transferred to Broadway, where it is being touted as a Tony-and-Pulitzer favorite. Sometimes such unanimity is a sign of distinction, but just as often it’s an indication that a play is going over big because it tells the audience precisely what it wants to hear—and nothing more. Such is the case with “What the Constitution Means to Me,” which is not without merit but is no more a masterpiece than Tarell Alvin McCraney’s “Choir Boy,” another recent hit that clangs the bell of cozy progressive sentiment.

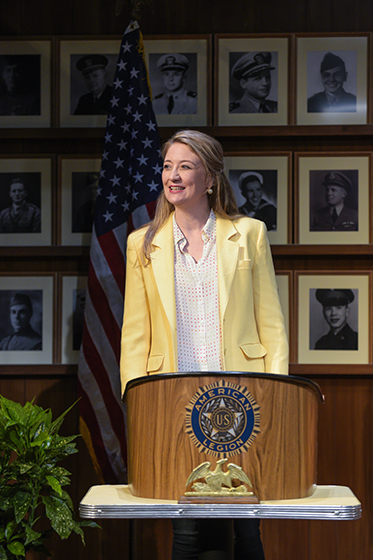

If you’ve seen any of Sarah Ruhl’s plays, you’ll recognize the tone and approach of “What the Constitution Means to Me,” which is very much in Ms. Ruhl’s aggressively ingratiating manner. It’s a three-person show in which Ms. Schreck plays herself in the present and at the age of 15, back in the days when she earned scholarship money by entering public-speaking tournaments. Her specialty was the American Legion-sponsored competition that gives her play its title. The scene is a small-town American Legion hall circa 1989, and the first part of the play consists of what Ms. Schreck claims to be a close replica of her prize-winning speech, interspersed with present-day reminiscences of her youth, family life and ancestors….

I mentioned a moment ago the tone of Ms. Schreck’s play and performance. It is the most Ruhl-like aspect of “What the Constitution Means to Me,” for the 15-year-old self whom she portrays in the show is, not to put too fine a point on it, effusively twee: “When I was a little girl, I had an imaginary friend named Reba McEntire. She was not related to the singer. Just because the Constitution does not proclaim the having of imaginary friends as a right does not mean I can be thrown in jail for being friends with Reba McEntire.” The point, I assume, is to show us what Ms. Schreck was like prior to her emergence as a mature, wised-up feminist who has put away childish things, though it turns out that her grown-up self is also given to Ruhl-style explosions of coyness…

These, however, have a different purpose, which is to make the serious section of her play more palatable. That part is in fact devastatingly harsh, for most of Ms. Schreck’s male ancestors, her father excluded, were vicious brutes who treated their spouses and children so savagely that the audience at the preview I attended gasped—as well it should have—to hear what they did. No amount of sugar can make such a spiky pill go down more smoothly, and Ms. Schreck’s account of her heritage of violence is by far the best part of “What the Constitution Means to Me.” The problem, one that is again familiar from Ms. Ruhl’s work, is that Ms. Schreck, for whatever reason, is rarely willing to grapple directly, at least not for very long, with the raw emotions triggered by her truth-telling. Hence she slathers them with a thick layer of Irony Lite…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.Heidi Schreck talks about What the Constitution Means to Me:

Glen Campbell and the Smothers Brothers sing “Thank You Very Much” on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour. This episode was originally telecast by CBS in February of 1968:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“His liking for Chinese art was an affair of the mind; in a world of increasing noise and hugeness, he turned in private to gentle, precise, and miniature things.”

James Hilton, Lost Horizon

“Conway remarked with a smile: ‘I suppose you’re certain, then, that no human affection can outlast a five-year absence?’

“‘It can, undoubtedly,’ replied the Chinese, ‘but only as a fragrance whose melancholy we may enjoy.”

James Hilton, Lost Horizon

Peter Pears and Julian Bream perform John Dowland’s “Fine knacks for ladies” and Philip Rosseter’s “What then is love but mourning” on the BBC in 1959:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

An ArtsJournal Blog