“People will believe anything, if it’s bad enough.”

Louis Auchincloss, The House of the Prophet

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

“People will believe anything, if it’s bad enough.”

Louis Auchincloss, The House of the Prophet

My Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column resumes today after a month-long hiatus. In it, I report on an important new regional museum initiative. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

The Metropolitan Museum of Art owns roughly 1,500,000 paintings, sculptures and other works of art. No more than 5% of them, however, can be viewed at any given time. The rest—including thousands of world-class pieces, more than enough to stock a satellite museum of similar quality—are locked up in storage. Much the same thing is true of every other major art museum in the world….

Is there a better way to handle outsized art collections? It’s hard for museums to sell off pieces from their permanent collections—and it should be. Museums hold works of art in trust for the public, not as negotiable assets that can be bought and sold at will. But as the New York Times pointed out in a recent story, their collections have grown so large in recent years that the cost and logistics of storage are fast becoming unmanageable.

Enter the Terra Foundation for American Art and Art Bridges, an organization founded by Alice Walton, the driving force behind Arkansas’ Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. These two groups have teamed up on a new initiative intended to encourage regional art museums to share their collections—one that in time might also prove to have the additionally desirable effect of helping to get masterpieces out of storage and put them to better use.

In April, Terra and Art Bridges gave $700,000 to the Philadelphia Museum of Art to support a program that will make it possible for the PMA to loan 16 works of art to eight smaller Pennsylvania museums, where they will be shown as part of exhibitions mostly drawn from the permanent collections of those museums. It’s the latest step in a long-term plan to underwrite large-scale exhibitions in Pennsylvania organized along similar lines….

Some of the exhibitions will have a local focus. Starting on Sept. 15, the Reading Public Museum is mounting a show called “Picturing Pennsylvania Barns” in which its “Hill Road,” a 1920 painting of a country barn by George Sotter, is hung alongside two important works by Charles Sheeler, one of which, “Bucks County Barn,” is a 1918 PMA-owned photograph of the same barn….

What excites me most about this project is that it is specifically encouraging one of our greatest art museums to lend works to its smaller neighbor institutions. In addition, though, my dream is that it will evolve over time into a much more ambitious collection-sharing program, one that gets larger numbers of important paintings out of storage and in front of the people….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

The New York Drama Critics’ Circle, which was founded in 1935 and of which I am a longtime member, voted yesterday afternoon to determine the winners of its eighty-fourth annual awards. They were announced immediately after the votes were counted:

• BEST PLAY: The Ferryman (Jez Butterworth)

• BEST AMERICAN PLAY: What the Constitution Means to Me (Heidi Schreck)

• BEST MUSICAL: Tootsie (David Yazbek and Robert Horn)

• SPECIAL CITATIONS: Irish Repertory Theatre; Page 73; Fiddler on the Roof in Yiddish

For the record, my choices were Tracy Letts’ Mary Page Marlowe for both best play and best American play and Conor McPherson’s Girl from the North Country for best musical. I voted for Tom Stoppard’s The Hard Problem for best foreign play, but the fact that the best-play award went to The Ferryman meant that no separate award was given in that category. I also voted for the Irish Repertory Theatre. (I have not seen Fiddler on the Roof in Yiddish or any work by Page 73.)

From the press release:

To read a detailed account of the proceedings, go here.The New York Drama Critics’ Circle comprises 19 drama critics from daily newspapers, magazines, wire services and websites based in the New York metropolitan area. The New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award, which has been awarded every year since 1936 to the best new play of the season (with optional awards for foreign or American plays, musicals and special achievements), is the nation’s second-oldest theater award, after the Pulitzer Prize for drama.

From 2009:

Read the whole thing here.The problem I had with “Peanuts” is the same problem I have with virtually all serial art: it isn’t meant to be consumed in bulk. A daily comic strip whose installments are free-standing rather than connected by strands of plot is an endless series of moments. To read it once a day is a fleeting pleasure. To read dozens of installments in a single sitting is to realize just how ephemeral that pleasure was….

“A young man who wants to get ahead must learn to hide his grudges. If he still has them when he gets to the top of the ladder, that’s a sign he’s picked the wrong ladder.”

Louis Auchlncloss, The House of the Prophet

I first learned that certain rich people had telephones in their cars from a short-lived TV series called Burke’s Law. Gene Barry, the star, played a wealthy Los Angeles homicide detective who was chauffeured to and from crime scenes in a Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud II that was equipped with a phone. I was seven years old when Burke’s Law made its debut on ABC in 1963, so the fact that Amos Burke had a phone in his Rolls must have made a huge impression on me, since I had no doubt thereafter that a car phone was the ne plus ultra of luxury.

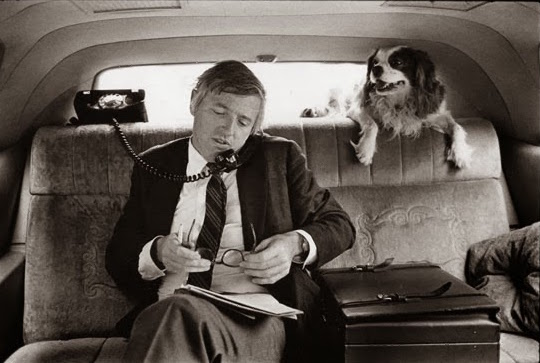

It wasn’t until I moved to New York in 1985 that I first got to know a person, William F. Buckley, Jr., who had a mobile phone in his stretch limo. Even then, I still found it to be fantastically ritzy. Had you told me in 1963—or 1985—that such phones would become obsolete long before I reached middle age, much less that I would live to see a fully mobile phone in every person’s pocket, be he rich or poor, I would have laughed in your face.

I’m sure I would have felt much the same way about the long-unimaginable prospect of owning a home videotape recorder. The Sony CV-2000, the first such device to be commercially marketed, cost $695 in 1965, the equivalent of $5,600 today, which put it far out of reach of people like my parents. Nevertheless, I bought my first VCR eighteen years later, and I soon took its life-changing existence for granted.

Most people see the present-day ubiquity of such devices as a chapter in the fast-moving history of technological change, which has transformed the daily life of the average American family almost beyond recognition. It’s easy to forget that as late as 1940, 45% of all Americans did not yet have “indoor plumbing,” meaning a flush toilet, a sink with a faucet, and a bathtub or shower. Today, by contrast, virtually all of us do. We can also eat all the caviar we want, the once-exorbitant price of that quintessential luxury good having been cut in half by the coming of cheap Chinese caviar that reportedly tastes just as good as the Russian kind.

In Chinatown, J.J. Gittes finds it impossible to understand why Noah Cross would be willing to do anything, up to and including murder, to corner the market on Los Angeles’ water supply. “Why are you doing it?” he asks Cross. “How much better can you eat? What can you buy that you can’t already afford?” To which Cross famously replies, “The future, Mr. Gittes—the future!” I’m not absolutely certain what he means when he says that, but I do know that whatever it is, Noah Cross’ future isn’t something I care to have. I’m content with the present—and the partner with whom I share it. Next to that pleasure, all others pale to the point of invisibility.

* * *

“Mobile Telephones,” a 1949 promotional short for the Bell System’s newly inaugurated Mobile Telephone System:

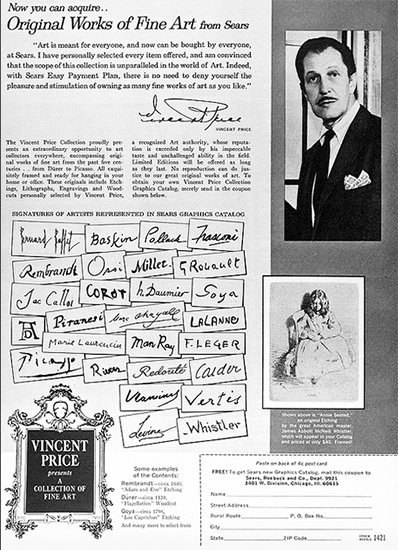

A 1962 training video made by Vincent Price for Sears in which he explained to the company’s salespeople how to market the Vincent Price Collection of Fine Art:

“Copland Portrait,” a 1975 TV documentary about the American composer directed by Terry Sanders:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“Wasn’t it Talleyrand who said, ‘After eighty, there are no enemies, only survivors’?”

Louis Auchlncloss, The House of the Prophet (this Talleyrand “quote” cannot be traced to a primary source)

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

An ArtsJournal Blog