“It occurs to me that of all Shakespeare’s plays King Lear is the one I have been and continue to be most moved by. It is probably the bleakest of the plays, the most unconsoling.”

Anthony Hecht, letter to John Van Doren, February 16, 2002 (courtesy of Anecdotal Evidence)Archives for 2019

Once again, with feeling

* * *

The commercial triumph of “Once,” which moved to Broadway in 2012, ran there for 1,168 performances and won eight Tony Awards, was one of the happiest—and least likely—theatrical success stories of the past decade. Nor is the story over yet: If you missed out on “Once,” or merely want to see whether it’s as good as you remember, Pennsylvania’s Bucks County Playhouse is giving it a warm-hearted revival directed by Travis Greisler that’s as satisfying as the original production, maybe even more so.

By all rights, “Once” shouldn’t have gotten to Broadway at all, much less become a smash hit. It’s a soft-spoken, small-scale show performed on an uncomplicated unit set by a cast of 13 singer-actors who play their own instruments. Nor is it a full-fledged musical: “Once,” which is based on John Carney’s 2007 film, feels more like a play with songs, and the folk-pop score, by Glen Hansard and Markéta Irglová, is nothing special. And while it’s a love story, it’s a very particular kind of love story, a should-they-or-shouldn’t-they tale of two Dubliners (Matt DeAngelis and Mackenzie Lesser-Roy) who fall hard for one another but have pressing responsibilities that pull them in opposite directions. A musical for adults, in other words, told with a forthrightness that’s guaranteed to put a lump in your throat….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.A video featurette about Once:

The twenty-five record albums that changed my life (24)

Various forms of the records-that-changed-my-life meme have been making the rounds lately, so I came up with my own version, which I call “The Twenty-Five Record Albums That Changed My Life.” I’m writing about one of these albums each weekday in the rough order in which I first heard them.

I didn’t stop listening to classical music in high school. Far from it: that was when I first heard The Rite of Spring, the songs of Fauré and Wolf, Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony, and the late piano pieces of Brahms, among countless other things. But my life was so full of music that it was impossible for me to focus on any one kind, nor did I care to do so. It wasn’t until I went off to college in Kansas City as a music major early in 1975 that I began once again to immerse myself in the classics, and to start making new, life-changing discoveries.

Back then I was still figuring out which kinds of music spoke to me most strongly and which ones didn’t, and I was looking for someone to be my composer, the one whose work would teach me what I liked and—yes—who I was. Under other circumstances it might well have been Aaron Copland, whose Appalachian Spring and Billy the Kid had hit me with overwhelming force in junior high school, but having embarked on a new life, it seemed logical for me to look for someone new, and that someone turned out to be Benjamin Britten.

I can’t remember how or why I connected with Britten, for I knew nothing about him or his music. I’d read about him in Stereo Review, of course, but he was only a name to me, an English composer of reputedly conservative inclination (whatever that meant) who wrote operas. Nor do I remember hearing about Britten in the classroom. All I know is that one Saturday afternoon I drove to a record store at a shopping mall in Independence, Missouri, and bought a copy of an album that contained what I had somehow found out was his most popular piece of music, the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings, a 1943 song cycle consisting of six settings of poems by John Cotton, Tennyson, Blake, Jonson, Keats, and the fifteenth-century Lyke-Wake Dirge, all framed by a pair of unaccompanied horn solos.

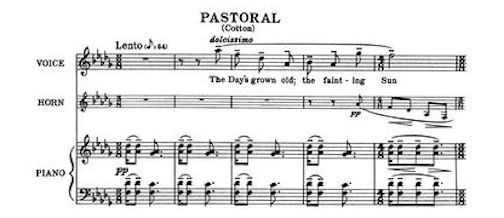

I brought the album back to my dorm room, put on my headphones, started listening, and was immediately transported, first by the mysterious introductory horn solo and then by Britten’s setting of Cotton’s “Pastoral,” a poem about sunset: The Day’s grown old, the fainting Sun/Has but a little way to run,/And yet his steeds, with all his skill,/Scarce lug the chariot down the hill.

Rarely in my life have I been so instantaneously overwhelmed as I was by “Pastoral,” though a few more years would go by before I attained sufficient musical sophistication to be able to fully understand why it had hit me so hard. It doesn’t look like much on the page, just a simple tune shared by the singer and horn player, accompanied by four-part string chords. Yet those deceptively uncomplicated-looking chords are anything but straightforward. Here as in his other middle-period masterpieces, Britten used tonal harmony with a piquant freshness and sense of surprise that were all his own.

“I need more chords,” Aaron Copland complained to Leonard Bernstein toward the end of his composing career. “I’ve run out of chords.” To listen to “Pastoral” is to realize that there will always be enough chords. All you have to do is know where to look….

I was certain that my discovery of the magical “Pastoral” was more than just another passing fancy. It spoke to me, as did the rest of the Serenade, with a directness and immediacy not unlike the miraculous sensation of falling in love at first sight (something that had yet to happen to me). I knew beyond doubt that whoever Benjamin Britten was, his music would henceforth play an important part in my life–and so it did, and does.

While I was no less intrigued by the singing of Peter Pears, whose reedy, nasal voice lacked the warmth of the Italian-style tenors I knew from grand opera but nonetheless spoke to me persuasively, it was Britten’s music that cast the spell. I believe as deeply today as I did in 1975 in the miracle that is tonality, the harmonic language of most Western classical music, and I continue to marvel at the uncanny individuality with which he used it throughout his career. Unlike Copland, whose inspiration failed him in late middle age, a harbinger of the Alzheimer’s disease that would put an end to his musical life, Britten never ran out of chords, and I have yet to tire of listening to them.

(To be continued)

* * *

Peter Pears, Barry Tuckwell, Benjamin Britten, and the London Symphony perform “Pastoral,” the first movement of Britten’s Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings, recorded in 1963:

Pears, Britten, and the English Chamber Orchestra perform “When most I wink,” the last movement of Britten’s Nocturne, Op. 60, on the BBC in 1964. The text is by Shakespeare:

Britten talks to an interviewer for the CBC in 1968:

* * *

To read about album #1, go here.

To read about album #2, go here.

To read about album #3, go here.

To read about album #4, go here.

To read about album #5, go here.

To read about album #6, go here.

To read about album #7, go here.

To read about album #8, go here.

To read about album #9, go here.

To read about album #10, go here.

To read about album #11, go here.

To read about album #12, go here.

To read about album #13, go here.

To read about album #14, go here.

To read about album #15, go here.

To read about album #16, go here.

To read about album #17, go here.

To read about album #18, go here.

To read about album #19, go here.

To read about album #20, go here.

.To read about album #21, go here.

.To read about album #22, go here.

.To read about album #23, go here.

Replay: Ray Charles plays “Li’l Darlin’”

Ray Charles plays Neal Hefti’s “Li’l Darlin’” with his touring band at the Newport Jazz Festival. This performance, which took place on July 2, 1960, is introduced by Willis Conover of the Voice of America:

Almanac: Disraeli on knowledge and equality

“It is knowledge that influences and equalises the social condition of man; that gives to all, however different their political position, passions which are in common, and enjoyments which are universal.”

Benjamin Disraeli, “The Value of Literature to Men of Business” (speech, October 23, 1844)

The twenty-five record albums that changed my life (23)

Various forms of the records-that-changed-my-life meme have been making the rounds lately, so I came up with my own version, which I call “The Twenty-Five Record Albums That Changed My Life.” I’m writing about one of these albums each weekday in the rough order in which I first heard them.

I don’t know what there is left to say about Bill Evans that hasn’t already been well said elsewhere. I (and many others) consider him to be the greatest jazz pianist in the world today. He has weathered decades, changes in the world’s musical tastes, and tragic personal problems. He has the strength of a warrior and the soul of a poet. He remains one of the simple but intellectual masters of modern piano interpretation. On every one of Bill’s albums in my collection (I’ve lost count of the number) I think I can feel his heart.

I wanted to run right out and buy a copy of Alone after reading that effusive paragraph, but such a thing wasn’t yet possible in Smalltown, U.S.A., in 1970, so I filed Reed’s review away in the back of my mind, went about my business, and—not surprisingly—forgot all about Evans. Then, four years later, Verve put out a two-disc greatest-hits collection of his recordings called Return Engagement that contained, among other things, a couple of tracks from Alone. I was by that time a regular mail-order customer of Chicago’s Rose Records, so I ordered a copy, more out of curiosity than anything else.

As soon as Return Engagement arrived, I put on the first track, Evans’ 1963 recording of Alex North’s “Love Theme from Spartacus.” To say that I was stunned by what came floating out of my speakers is an understatement. Even though the middle part of “Love Theme from Spartacus” is a kind of jazz waltz, the opening and closing sections sounded nothing like any kind of jazz I’d ever heard. At times they hinted at Debussy or Ravel, but there was nothing derivative about them: they were, rather, the musical equivalent of a cloudy night sky filled with fireflies and brightly shining stars. I was so bowled over that it didn’t hit me at first that what I was hearing was one pianist playing three separate tracks, two of them overdubbed. All I heard was the music, and as I listened to it, I thought: This is the way I’d like to play piano.

Many jazz musicians resemble their music. Who could have looked more worldly-wise than Duke Ellington, or wittier than Paul Desmond? But sometimes a musician embodies a contradiction, and then you can read it off his face, just as you can see a fault line snaking through a tranquil landscape. Such was the case with Bill Evans. His shining tone and cloudy pastel harmonies transformed such innocuous pop songs as “Young and Foolish” and “The Boy Next Door” into fleeting visions of infinite grace. Yet the bespectacled, cadaverous ruin who sat hunched over the keyboard like a broken gooseneck lamp seemed at first glance incapable of such Debussyan subtlety; something, one felt sure, must have gone terribly wrong for a man who played like that to have looked like that.

I never met Evans, and I’m glad I didn’t. I think he would have been far too painfully sad a person to want to know. But I’ve spent much of the past half-century listening closely to his music, including “Love Theme from Spartacus,” time enough and more to know that it is, at least for me, inexhaustibly beautiful—and that it’s still the way I’d like to play piano, if I could.

(To be continued)

* * *

Bill Evans plays Alex North’s “Love Theme from Spartacus” on Conversations With Myself, released in 1963:

The Bill Evans Trio plays “My Foolish Heart” on the BBC in 1965. Chuck Israels is the bassist, Larry Bunker the drummer:

Bill Evans is interviewed by Chris Albertson in 1970:

* * *

To read about album #1, go here.

To read about album #2, go here.

To read about album #3, go here.

To read about album #4, go here.

To read about album #5, go here.

To read about album #6, go here.

To read about album #7, go here.

To read about album #8, go here.

To read about album #9, go here.

To read about album #10, go here.

To read about album #11, go here.

To read about album #12, go here.

To read about album #13, go here.

To read about album #14, go here.

To read about album #15, go here.

To read about album #16, go here.

To read about album #17, go here.

To read about album #18, go here.

To read about album #19, go here.

To read about album #20, go here.

.To read about album #21, go here.

.To read about album #22, go here.

Almanac: Eric Hoffer on freedom and equality

“Where freedom is real, equality is the passion of the masses. Where equality is real, freedom is the passion of a small minority.”

Eric Hoffer, The True Believer

The twenty-five record albums that changed my life (22)

Various forms of the records-that-changed-my-life meme have been making the rounds lately, so I came up with my own version, which I call “The Twenty-Five Record Albums That Changed My Life.” I’m writing about one of these albums each weekday in the rough order in which I first heard them.

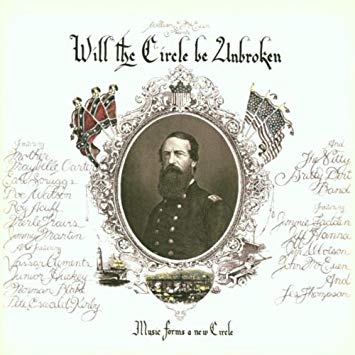

22. The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, Will the Circle Be Unbroken (United Artists)

I took no note of Will the Circle Be Unbroken when it came out because I didn’t listen to country music. The kind of country that you heard on the radio in 1972 in Smalltown, U.S.A., was mostly the kind for which I had no use whatsoever and still don’t, the insipid “Nashville Sound” 101-Strings ballads that even now can send me running from the room with hands clamped on ears unless they’re sung by the ennobling likes of George Jones.

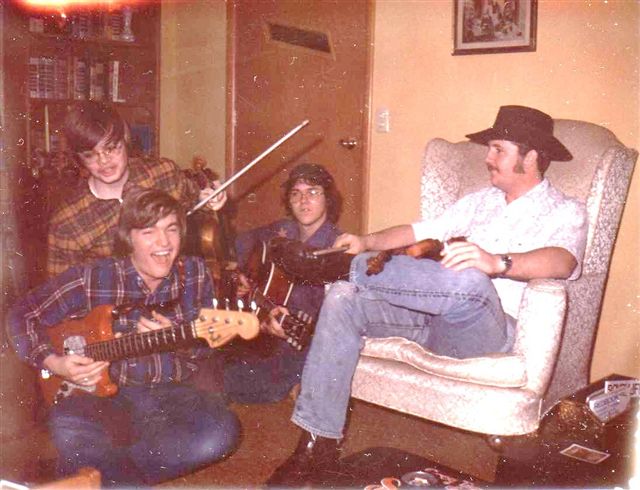

It was Greg Tanner who changed my mind about the other kind of country music. He was a couple of years older than me, and we met when I entered high school and started playing in the school orchestra. He was a chunky, funny guy with the thickest hick accent I’d ever heard, which he used to conceal the fact that he was both intelligent and sensitive, something he didn’t care for anybody to know. He was also a pretty decent violinist and a very good fiddler who used to play bluegrass and country music for fun during our rehearsal breaks. I was fascinated by the unfamiliar tunes that he tossed off, and in due course we became friends and teamed up with two of his other friends, Ken Harbin and Chuck Hanna, to start a four-piece country-and-bluegrass band that we called Sour Mash.

Greg, Ken, Chuck, and I spent the next couple of years gigging around Smalltown and its environs. Chuck had his own circle of intimates and mostly kept to himself, but Greg, Ken and I were soon spending most of our weekends hanging out together, something I’d never done with male friends of my own age. I wrote about those weekends many years later in a memoir of my small-town childhood and youth:The three of us did more than just play music and go cruising. We ate meals together. We went camping together. We spent time with each other’s families. We drove out to a deserted bean field one hot summer afternoon and shot bottle rockets at each other. Losing an eye or a finger would have been a stiff price to pay for a good time, but I probably would have paid it without complaining, for I knew the value of my friendship with Greg and Ken. They did their best to teach me how to be a regular guy, taking me by the hand and leading me through the nighttime world of truck stops and chicken-fried steak. I could do little for them in return except play bass and serve as a full-time butt for their practical jokes, but that seemed to be enough. I spent hours watching them shoot pool and drink beer in a seedy dump on Highway 61. One night I overheard Greg talking about me to a fellow at the bar who was wondering why I tagged along. “Hell, yes, he’s strange,” Greg said, “but who gives a shit? He can play the goddamn bass, can’t he? What do you want? A quarterback?”

The friendship was more important to me than the music we made, but the music mattered, too, far more than I understood at first. I learned how to play it from Will the Circle Be Unbroken, which contains such down-home standards as “I Saw the Light,” “Lonesome Fiddle Blues,” “Lost Highway,” “Nine-Pound Hammer,” “Orange Blossom Special,” and “Wreck on the Highway,” all of which insinuated their way into my smartest-boy-in-town blood and became part of my musical DNA. Before long I’d fallen in love with the rootsy, life-is-like-this simplicity of old-time, stone-hard country music. I love it as much now as I did back then—probably even more, since I’ve lived long enough to have felt the soul-wracking hurt that it so often portrays so honestly and well.

In time the four of us graduated from high school, went off to make our separate ways in the world, and mostly lost track of one another save for increasingly infrequent yet always heartfelt reunions. Greg and Chuck are dead now, but Ken, who lives in Kentucky, still stays in touch with me via e-mail, and once in a while we share our unfaded memories of the days when we played music and pinball together and learned how much it means to be a friend.

(To be continued)

* * *

“Avalanche,” from the original Will the Circle Be Unbroken album, played by Vassar Clements and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band:

“Tennessee Stud,” from the original Will the Circle Be Unbroken album, played by Doc Watson and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band:

“Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” performed live in 1990 on Austin City Limits by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and a group of guest artists, including Del McCoury:

* * *

To read about album #1, go here.

To read about album #2, go here.

To read about album #3, go here.

To read about album #4, go here.

To read about album #5, go here.

To read about album #6, go here.

To read about album #7, go here.

To read about album #8, go here.

To read about album #9, go here.

To read about album #10, go here.

To read about album #11, go here.

To read about album #12, go here.

To read about album #13, go here.

To read about album #14, go here.

To read about album #15, go here.

To read about album #16, go here.

To read about album #17, go here.

To read about album #18, go here.

To read about album #19, go here.

To read about album #20, go here.

.To read about album #21, go here.