Various forms of the records-that-changed-my-life meme have been making the rounds lately, so I came up with my own version, which I call “The Twenty-Five Record Albums That Changed My Life.” I’m writing about one of these albums each weekday in the rough order in which I first heard them.

I didn’t stop listening to classical music in high school. Far from it: that was when I first heard The Rite of Spring, the songs of Fauré and Wolf, Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony, and the late piano pieces of Brahms, among countless other things. But my life was so full of music that it was impossible for me to focus on any one kind, nor did I care to do so. It wasn’t until I went off to college in Kansas City as a music major early in 1975 that I began once again to immerse myself in the classics, and to start making new, life-changing discoveries.

Back then I was still figuring out which kinds of music spoke to me most strongly and which ones didn’t, and I was looking for someone to be my composer, the one whose work would teach me what I liked and—yes—who I was. Under other circumstances it might well have been Aaron Copland, whose Appalachian Spring and Billy the Kid had hit me with overwhelming force in junior high school, but having embarked on a new life, it seemed logical for me to look for someone new, and that someone turned out to be Benjamin Britten.

I can’t remember how or why I connected with Britten, for I knew nothing about him or his music. I’d read about him in Stereo Review, of course, but he was only a name to me, an English composer of reputedly conservative inclination (whatever that meant) who wrote operas. Nor do I remember hearing about Britten in the classroom. All I know is that one Saturday afternoon I drove to a record store at a shopping mall in Independence, Missouri, and bought a copy of an album that contained what I had somehow found out was his most popular piece of music, the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings, a 1943 song cycle consisting of six settings of poems by John Cotton, Tennyson, Blake, Jonson, Keats, and the fifteenth-century Lyke-Wake Dirge, all framed by a pair of unaccompanied horn solos.

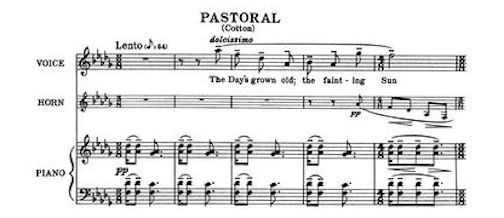

I brought the album back to my dorm room, put on my headphones, started listening, and was immediately transported, first by the mysterious introductory horn solo and then by Britten’s setting of Cotton’s “Pastoral,” a poem about sunset: The Day’s grown old, the fainting Sun/Has but a little way to run,/And yet his steeds, with all his skill,/Scarce lug the chariot down the hill.

Rarely in my life have I been so instantaneously overwhelmed as I was by “Pastoral,” though a few more years would go by before I attained sufficient musical sophistication to be able to fully understand why it had hit me so hard. It doesn’t look like much on the page, just a simple tune shared by the singer and horn player, accompanied by four-part string chords. Yet those deceptively uncomplicated-looking chords are anything but straightforward. Here as in his other middle-period masterpieces, Britten used tonal harmony with a piquant freshness and sense of surprise that were all his own.

“I need more chords,” Aaron Copland complained to Leonard Bernstein toward the end of his composing career. “I’ve run out of chords.” To listen to “Pastoral” is to realize that there will always be enough chords. All you have to do is know where to look….

I was certain that my discovery of the magical “Pastoral” was more than just another passing fancy. It spoke to me, as did the rest of the Serenade, with a directness and immediacy not unlike the miraculous sensation of falling in love at first sight (something that had yet to happen to me). I knew beyond doubt that whoever Benjamin Britten was, his music would henceforth play an important part in my life–and so it did, and does.

While I was no less intrigued by the singing of Peter Pears, whose reedy, nasal voice lacked the warmth of the Italian-style tenors I knew from grand opera but nonetheless spoke to me persuasively, it was Britten’s music that cast the spell. I believe as deeply today as I did in 1975 in the miracle that is tonality, the harmonic language of most Western classical music, and I continue to marvel at the uncanny individuality with which he used it throughout his career. Unlike Copland, whose inspiration failed him in late middle age, a harbinger of the Alzheimer’s disease that would put an end to his musical life, Britten never ran out of chords, and I have yet to tire of listening to them.

(To be continued)

* * *

Peter Pears, Barry Tuckwell, Benjamin Britten, and the London Symphony perform “Pastoral,” the first movement of Britten’s Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings, recorded in 1963:

Pears, Britten, and the English Chamber Orchestra perform “When most I wink,” the last movement of Britten’s Nocturne, Op. 60, on the BBC in 1964. The text is by Shakespeare:

Britten talks to an interviewer for the CBC in 1968:

* * *

To read about album #1, go here.

To read about album #2, go here.

To read about album #3, go here.

To read about album #4, go here.

To read about album #5, go here.

To read about album #6, go here.

To read about album #7, go here.

To read about album #8, go here.

To read about album #9, go here.

To read about album #10, go here.

To read about album #11, go here.

To read about album #12, go here.

To read about album #13, go here.

To read about album #14, go here.

To read about album #15, go here.

To read about album #16, go here.

To read about album #17, go here.

To read about album #18, go here.

To read about album #19, go here.

To read about album #20, go here.

.To read about album #21, go here.

.To read about album #22, go here.

.To read about album #23, go here.