Various forms of the records-that-changed-my-life meme have been making the rounds lately, so I came up with my own version, which I call “The Twenty-Five Record Albums That Changed My Life.” I’ll write about one of these albums each weekday in the rough order in which I first heard them.

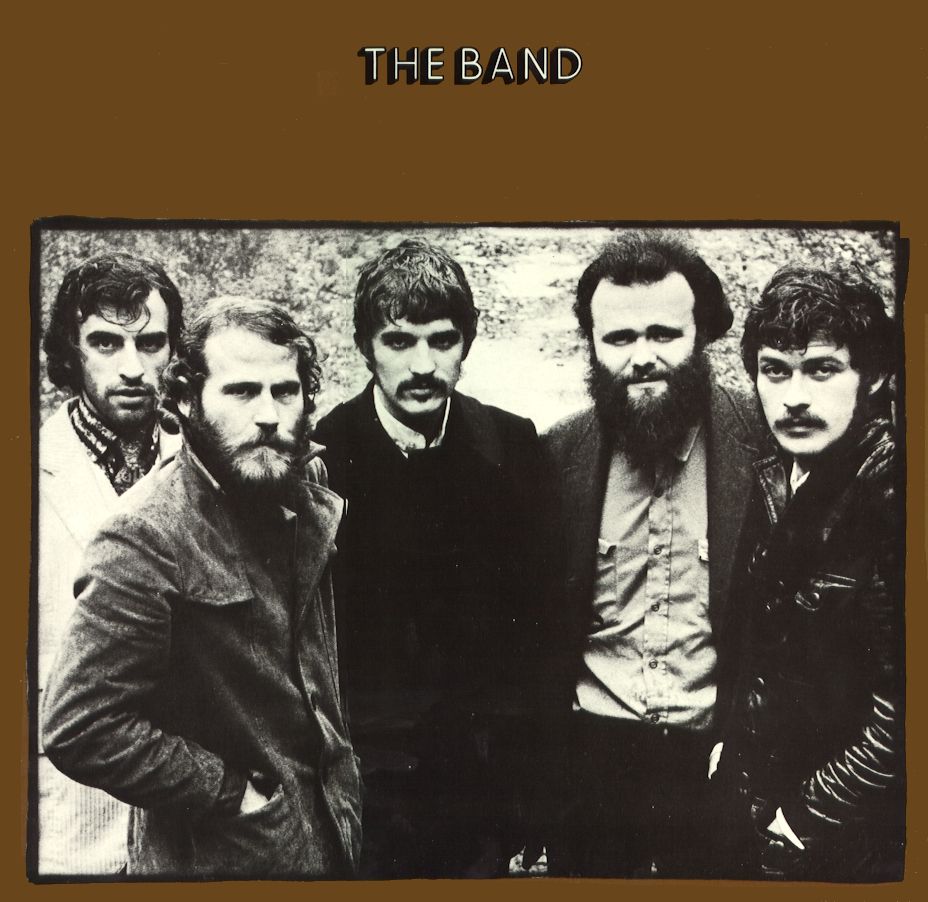

Popularly known to rock aficionados as the “brown album,” The Band is, in my firmly held opinion, the best rock-and-roll record ever made and one of the best pop records of any kind, a work of creative genius in which rock, country, and folk are blended together into an indissoluble amalgam for which the term “Americana” might have been coined. What pop music should be, it is.

The Band was reviewed in Rolling Stone by Ralph J. Gleason, who is now mainly remembered as a jazz journalist but was no less interested in other kinds of pop music, and whose 1969 review, which I read in book form two years after the fact, made me go right out and buy that extraordinary record. I can’t remember having read a review that conveyed more clearly in words alone the essential quality of a work of musical art:

I hear these songs as a sound track to James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, to the real documentary of the American truth. They are sparse songs with never a superfluous note or an unnecessary syllable. And yet the sparseness, like a Picasso line, is so right that it implies everything needed. Lean and dusty, perhaps, like Henry Fonda walking down the road at the beginning of Grapes of Wrath, it says volumes in a phrase…

With their flashing images of the American continental landscape…they speak for the continent in “King Harvest (Has Surely Come).” They could have called the album America, Robbie says, and after you play it a few times you know what he means. We live in these cities and we forget that there is more than 3000 miles between New York and the smog of Los Angeles and those 3000 miles are deeply rooted to another world in another time and with another set of values. “King Harvest” takes us there.

The hymn-like quality of the voicings, the use of counterpoint and contrapuntal rhythms by the singers, the weaving of the voices in and out into a pattern that grows each time you hear it, are the things that make the sound of this music so compelling. In “King Harvest,” as in other songs, individual sections with contrasting timbres, moods, rhythms and sounds are juxtaposed to make a totality that is so open it can cover whatever you feel. The sense of doom, almost Biblical in its prophetic warning, of “Look Out Cleveland” is unique in contemporary popular song, so far removed from the obvious morbidity of some of the songs of past years as to be an adult to their child. (This music, of course, is mature, made by men who know who they are and what they want to do. Its appeal to the teenybopper Top 40 audience seems, on the evidence, to be limited.)

Maybe so, but the appeal of The Band to my fifteen-year-old small-town self was overwhelming. I wouldn’t have put it this way back then, but it was the first pop album I’d heard that spoke to me with the same profundity and complexity as did the best jazz and classical music—and if I’d known anything about country, I would have known that it is also as true to the pain and uncertainty of adult life as any of the songs of Hank Williams or Bill Monroe. Gleason nailed it: The Band is mature music.

In retrospect, I simply can’t understand why such a record hit me where I lived. I was anything but mature in 1971. Yet I have no doubt that it did so, especially “King Harvest (Has Surely Come),” an unsentimentally told tale of the suffering and courage of a southern farmer which made me weep then and does so today. After listening to it for a half-century, I can say with the absolute assurance that only the passage of time can give that “King Harvest” is a truly great work of popular art, a miniature masterpiece that is directly comparable in quality to, say, Frank Sinatra’s “One for My Baby,” George Jones’ “The Grand Tour,” Skip James’ “Devil Got My Woman,” or Charlie Parker’s “Parker’s Mood.” (Or Schubert’s “Wanderers Nachtlied II,” for that matter.) Having once heard it, I knew what popular music at its very best was capable of saying about human experience, and have never again gladly settled for anything less.

(To be continued)

* * *

The Band plays “King Harvest (Has Surely Come),” from The Band, recorded in 1969. The members of the group are Rick Danko on bass, Levon Helm on drums, Garth Hudson on organ, Richard Manuel on piano and lead vocals, and Robbie Robertson on guitar. (On this track, John Simon also plays electric piano.) The song is by Robertson:

The Band rehearses “King Harvest” at Robbie Robertson’s studio in Woodstock, N.Y., in 1969:

To hear me talk in detail about The Band with Scot Bertram and Jeff Blehar in 2018, go here.* * *

To read about album #1, go here.

To read about album #2, go here.

To read about album #3, go here.

To read about album #4, go here.

To read about album #5, go here.

To read about album #6, go here.

To read about album #7, go here.

To read about album #8, go here.

To read about album #9, go here.

To read about album #10, go here.

To read about album #11, go here.

To read about album #12, go here.

To read about album #13, go here.

To read about album #14, go here.

To read about album #15, go here.

To read about album #16, go here.

To read about album #17, go here.

To read about album #18, go here.