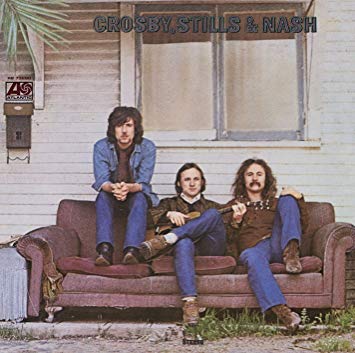

Various forms of the records-that-changed-my-life meme have been making the rounds lately, so I came up with my own version, which I call “The Twenty-Five Record Albums That Changed My Life.” Throughout the coming month, I’ll write about one of these albums each weekday in the rough order in which I first heard them.

Whatever the reasons, Crosby, Stills & Nash were big in 1969, and got even bigger when Neil Young, also formerly of Buffalo Springfield, joined the group a year later for its second album, Déjà Vu. I heard them on the radio, saw them on stage in Woodstock, and listened to both albums over and over again, trying—mostly in vain—to play their self-written songs on the not-very-good acoustic guitar that my father had obligingly bought me. I actually talked my mother into taking down the lyrics to “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes” in shorthand so that I could sing them correctly. Had I started a band of my own, I’m sure that’s just what I would have wanted it to sound like.

Before long, though, I started to lose my taste for their grit-free ensemble style, which increasingly struck me as more than a little bit sugary as I encountered other, more harder-edged varieties of rock and roll. It is, needless to say, perfectly possible to like both Crosby, Stills & Nash and Live at Leeds, but most listeners do end up tilting more or less strongly one way or the other.

As for their songs, I now blush to admit that I used to be thrilled by the lyrics, most of which now strike me as the worst kind of irony-challenged pop pseudo-profundity. Take “Wooden Ships,” in which Crosby, Stills, and Paul Kantner, one of the founding members of Jefferson Airplane, portrayed a world destroyed by nuclear war and imagined themselves as “the few survivors, escaping on a boat to create a new civilization.” I’d forgotten until I listened to it the other day for the first time in years that “Wooden Ships” has what must be the most shy-making opening line of any of the once-beloved rock songs of my youth: “If you smile at me, I will understand/’Cause that is something everybody, everywhere does/In the same language.” What can I tell you? We boomers couldn’t get enough of that kind of thing.

To be sure, I can still appreciate and respect the immaculate craftsmanship of Crosby, Stills & Nash, which is the squeaky-clean embodiment of what instrumentalists call “clean picking.” Moreover, there are a couple of songs that I continue to enjoy, above all Crosby’s “Guinnevere,” a genuinely haunting ballad that Miles Davis, of all people, liked enough to cover in his latter phase as a sort-of-rocker. Of the two dozen albums on this list, though, Crosby, Stills & Nash is the one to which I have returned least often in adulthood. Whatever its other virtues, most of it simply isn’t adult fare, not in the way that Miles and the Beatles are capable of holding the attention of mature ears and minds. It is in every way music by and for the young, and thus can have little to say to older people beyond reminding them of how very young they were once upon a time.

(To be continued)

* * *

“Guinnevere,” from Crosby, Stills & Nash:

Crosby, Stills & Nash perform “Wooden Ships” at Woodstock in 1969:

* * *

To read about album #1, go here.

To read about album #2, go here.

To read about album #3, go here.

To read about album #4, go here.

To read about album #5, go here.

To read about album #6, go here.

To read about album #7, go here.

To read about album #8, go here.

To read about album #9, go here.

To read about album #10, go here.

To read about album #11, go here.

To read about album #12, go here.

To read about album #13, go here.