“To be a writer is to be an autodidact, with all the limitations, gaps, and gaucheries typical of the autodidact, who belabors clichés as though they were sacral revelation.”

Cynthia Ozick, “Toward a New Yiddish”

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

“To be a writer is to be an autodidact, with all the limitations, gaps, and gaucheries typical of the autodidact, who belabors clichés as though they were sacral revelation.”

Cynthia Ozick, “Toward a New Yiddish”

Allegra Kent, Conrad Ludlow, and the New York City Ballet dance the second movement of George Balanchine’s Symphony in C. The score is Georges Bizet’s Symphony in C, composed shortly after Bizet turned seventeen. This performance was filmed in a Berlin studio in 1973:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“In any modern city, a great deal of our energy has to be expended in not seeing, not hearing, not smelling. An inhabitant of New York who possessed the sensory acuteness of an African Bushman whould very soon go mad.”

W.H. Auden, “The Justice of Dame Kind”

From 2006:

Read the whole thing here.I set my iBook on shuffle play the other night and sat down at the kitchen table to fill up my seven-day pillbox. (Don’t let anybody tell you that the life of a Manhattan drama critic isn’t exciting!) As Aimee Mann started singing “Deathly,” I glanced at the clock, saw that it was eleven, and suddenly found myself remembering a conversation I had thirty-odd years ago with a long-lost college friend. She was a slightly older married woman who had long, ash-blonde hair, thin legs, and a bone-dry sense of humor, all of which I found irresistibly (and unrequitedly) appealing. Those were the days when I was hosting a late-night jazz show on the campus radio station, and my friend remarked that she liked it when I played “eleven o’clock music.”

“What’s eleven o’clock music?” I asked innocently.

“Oh, you know,” she said. “Music to…you know. That’s when my husband and I like to do it.”

This offhand remark promptly triggered a near-incapacitating spasm of jealousy…

“One of the main horrors of journalism is having to produce appropriate emotions for every public event.”

Auberon Waugh, diary entry, October 26, 1973

Various forms of the records-that-changed-my-life meme have been making the rounds lately, so I came up with my own version, which I call “The Twenty-Five Record Albums That Changed My Life.” I’ve written about one of these albums each weekday in the rough order in which I first heard them.

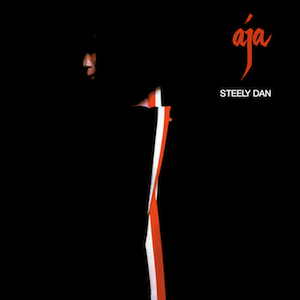

It stood to reason, then, that Steely Dan’s Aja should have hit me hard when it came out in the fall of 1977. For Aja wasn’t a fusion album, even though the title track featured a tenor saxophone solo by none other than Miles Davis’ Wayne Shorter: it was, rather, a rock album, but one made by two pop musicians, Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, who had fully assimilated the language of jazz and integrated it into their way of thinking about pop music. It was, at bottom and in every sense of the phrase, a musician’s album.

Michael Duffy understood this—up to a point, anyway—when he reviewed Aja for Rolling Stone:Aja will continue to fuel the argument by rock purists that Steely Dan’s music is soulless, and by its calculated nature antithetical to what rock should be. But this is in many ways irrelevant to a final evaluation of this band, the only group around with no conceptual antecedent from the Sixties. Steely Dan’s six albums contain some of the few important stylistic innovations in pop music in the past decade. By returning to swing and early be-bop for inspiration—before jazz diverged totally from established conventions of pop-song structure—Fagen and Becker have overcome the amorphous quality that has plagued most other jazz-rock fusion attempts.

“Peg” and “Josie” illustrate this perfectly: tight, modal tunes with good hooks in the choruses, solid beats with intricate counterrhythms and brilliantly concise guitar solos. Like most of the rest of Aja. these songs are filled out with complex horn charts, synthesizers and lush background vocals that flirt with schmaltzy L.A. jazz riffs. When topped by Fagen’s singing, they sound like production numbers from an absurdist musical comedy….

That said, it’s true that I didn’t read Duffy’s review, or anything else about Aja, until many years later. I simply bought the album when it came out, put on “Black Cow,” the first track, and understood in a single, all-encompassing flash of perception that this was my kind of rock, and always would be. I’d experienced the same kind of aesthetic revelation when, a year or two earlier, I saw Chinatown, my first film noir, on TV. It was as though I’d pulled on a bespoke suit for the first time: by wearing it, I knew who I was. Small wonder that I spent hours in the practice room, figuring out the changes to “Deacon Blues” by ear. I was determined to make them my own—and I did.

I’ve kept on listening to pop music, and making fresh discoveries about it, in the forty-two years since Aja came out. But none of those subsequent discoveries has been truly life-changing, at least not in the way that my first hearing of Aja permanently changed my relationship to the music of my youth. From then on, I approached pop music as an adult, and what I wrote about The Band in this space the other day applies with equal force to Aja: “Having once heard it, I knew what popular music at its very best was capable of saying about human experience, and have never again gladly settled for anything less.”

(Last in the series)

* * *

“Black Cow,” the first track from Aja:

A video featurette about the making of “Peg”:

A video featurette about the making of “Deacon Blues”:

* * *

To read about album #1, go here.

To read about album #2, go here.

To read about album #3, go here.

To read about album #4, go here.

To read about album #5, go here.

To read about album #6, go here.

To read about album #7, go here.

To read about album #8, go here.

To read about album #9, go here.

To read about album #10, go here.

To read about album #11, go here.

To read about album #12, go here.

To read about album #13, go here.

To read about album #14, go here.

To read about album #15, go here.

To read about album #16, go here.

To read about album #17, go here.

To read about album #18, go here.

To read about album #19, go here.

To read about album #20, go here.

To read about album #21, go here.

To read about album #22, go here.

To read about album #23, go here.

To read about album #24, go here.

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau sings “Der Leiermann,” a song from Franz Schubert’s Winterreise, accompanied by Alfred Brendel. This performance, subtitled in English, was taped for German TV in 1979:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“It occurs to me that of all Shakespeare’s plays King Lear is the one I have been and continue to be most moved by. It is probably the bleakest of the plays, the most unconsoling.”

Anthony Hecht, letter to John Van Doren, February 16, 2002 (courtesy of Anecdotal Evidence)An ArtsJournal Blog