“Time goes by, reputation increases, ability declines.”

Dag Hammarskjöld, Markings

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

“Time goes by, reputation increases, ability declines.”

Dag Hammarskjöld, Markings

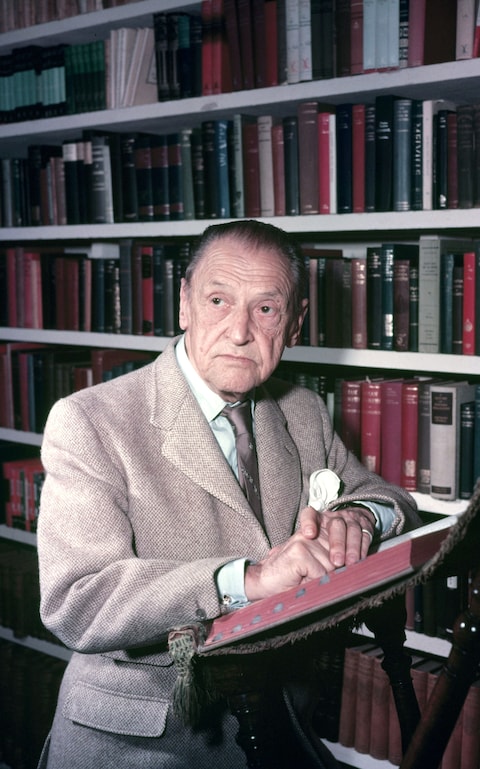

Orson Welles talks with Huw Wheldon about Citizen Kane on Monitor, originally telecast by the BBC on March 13, 1960:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“Her finely touched spirit had still its fine issues, though they were not widely visible. Her full nature, like that river of which Alexander broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.”

George Eliot, Middlemarch

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, I write about a new book by Rob Kapilow whose subject is American popular song. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

The “listicle,” a name used by writers and editors to refer to a piece that consists mainly or entirely of a list—the five best restaurants in New York, the 10 scariest movies of the ’70s, the 25 greatest plays of the 20thcentury—has become in recent years a staple of contemporary cultural journalism. It’s easy to see why: Listicles can be thrown together without excessive effort and are famously effective as clickbait. Precisely for that reason, though, they tend not to have much staying power, nor does the genre typically translate well into book form.

That said, there are exceptions to all journalistic rules, and the latest of these is Rob Kapilow’s “Listening for America: Inside the Great American Songbook From Gershwin to Sondheim” (Liveright), a listicle-style book whose publication earlier this month put me in mind of two other infectiously readable books that take a similar approach to their subjects.

The first one is W. Somerset Maugham’s “Great Novelists and Their Novels,” a volume of essays based on a piece that Maugham published in 1948 in Redbook, a magazine best known today for such listicles as “Thirteen Positive Benefits of Spending Time with Family During the Holidays.” Time was, though, when Redbook also published first-rate fiction by authors as diverse as Edith Wharton and Dashiell Hammett (“The Thin Man” first saw print there). Maugham was for many years a regular contributor, and in addition to writing dozens of crisply wrought short stories for Redbook, he also preached the virtues of such classics as “The Brothers Karamazov,” “David Copperfield,” “Madame Bovary,” “Pride and Prejudice” and “War and Peace” in a listicle that he later expanded into a series of essays for the Atlantic Monthly….

Less well known but just as worthy of note is Bernard Shore’s “Sixteen Symphonies,” a book published in 1950 by the then-principal violist of the BBC Symphony. In addition to being a distinguished instrumentalist, Shore was also a gifted writer, and during his decade-long tenure at the BBC, he performed under such legendary conductors as Serge Koussevitzky, Arturo Toscanini and Bruno Walter. “Sixteen Symphonies” is a memoir-like book in which he described the experience of playing the classics for great and not-so-great conductors, eschewing gossipy tale-telling to consider the art of orchestra playing from an insider’s point of view.

I thought of “Sixteen Symphonies” in particular as I read Mr. Kapilow’s “Listening for America.” The author, who is himself a conductor and musical commentator, is best known for “What Makes It Great,” a series of NPR radio commentaries in which he talks about the inner workings of familiar pieces of classical music in close but easily comprehensible detail. It turns out, though, that Mr. Kapilow is no less passionate an advocate for the Broadway musical…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.Rob Kapilow talks about “Over the Rainbow,” one of the songs discussed in Listening for America:

* * *

Bedlam’s small-scale revival of Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible,” directed by Eric Tucker and performed by a cast of 14, has opened off Broadway after a preliminary run earlier this season at the Nora Theatre Company in Cambridge, Mass. Here’s part of what I wrote about it then: “The animating premise of [Mr. Tucker’s] new staging…is wholly in keeping with the #MeToo moment: ‘In a culture in which power resides in the hands of men—who do you trust?’ If his statement of purpose sounds suspiciously reductive to you, fear not: Mr. Tucker is the least reductive of artists, and his forceful, fast-moving ‘Crucible’ will send you home filled not with smug self-confidence but anxiety-making doubt….”

* * *

Read the whole thing here.Eric Tucker talks about The Crucible:

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli plays Chopin’s B Minor Mazurka, Op. 33/4, on Italian TV in 1965:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“He was no good in discussion, not because any amount of argument could shake his faith, but because the mere fact of hearing another voice disconcerted him painfully, confusing his thoughts at once—these thoughts that for so many years, in a mental solitude more barren than a waterless desert, no living voice had ever combatted, commented, or approved.”

Joseph Conrad, The Secret Agent

* * *

When the AIDS epidemic laid waste to a generation of gay men, it simultaneously forced those who had been rejected by their families to come together as a community to cope with the devastation wrought by the disease. The story of how they did so, and the cascading effect that their heroic efforts would have on successive generations of gays in America, is the subject of “The Inheritance,” Matthew Lopez’s new two-part play, which was reviewed with wild enthusiasm when it ran in London’s West End in 2018. The critical consensus was that Mr. Lopez had written a stage epic worthy of comparison with Tony Kushner’s “Angels in America.” But while such comparisons were inevitable, “The Inheritance” fails to justify them. Ambitious though it is, “The Inheritance,” whose two installments run for well over six hours, is at once sentimental and static—far too much of it feels like a novel being read out loud from cover to cover—and the parts that work, poignant though they often are, fail to redeem those that don’t….

“The Inheritance” is fundamentally novelistic in method and scope, so much so that large parts of it are driven not by dialogue but by third-person narration that is passed from actor to actor: “Eric recognized within the first few minutes of their first date Toby’s potential for greatness.” “And also his capacity for destruction.” “Both possibilities attracted him.” As a result, far too much of the play is told, not shown, and I quickly grew impatient with Mr. Lopez’s unwillingness to let the audience watch what is happening instead of forcing them to hear about it over and over again.….

* * *

To read my review of The Inheritance, go here.The trailer for the West End production of The Inheritance:

An ArtsJournal Blog