Various forms of the records-that-changed-my-life meme have been making the rounds lately, so I came up with my own version, which I call “The Twenty-Five Record Albums That Changed My Life.” Throughout the coming month, I’ll write about one of these albums each weekday in the rough order in which I first heard them.

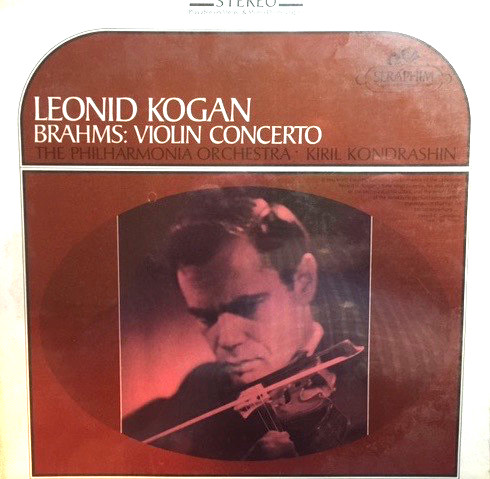

15. Leonid Kogan with Kiril Kondrashin and the Philharmonia Orchestra, Brahms D Major Violin Concerto, Op. 77 (Seraphim)

Brahms has always been one of the classical composers who means the most to me. My love for his music started here.

(To be continued)

* * *

Leonid Kogan, Kiril Kondrashin, and the Philharmonia Orchestra perform the Brahms Violin Concerto in 1958:

* * *

To read about album #1, go here.

To read about album #2, go here.

To read about album #3, go here.

To read about album #4, go here.

To read about album #5, go here.

To read about album #6, go here.

To read about album #7, go here.

To read about album #8, go here.

To read about album #9, go here.

To read about album #10, go here.

To read about album #11, go here.

To read about album #12, go here.

To read about album #13, go here.

To read about album #14, go here.