Various forms of the records-that-changed-my-life meme have been making the rounds lately, so I came up with my own version, which I call “The Twenty-Five Record Albums That Changed My Life.” Throughout the coming month, I’ll write about one of these albums each weekday in the rough order in which I first heard them.

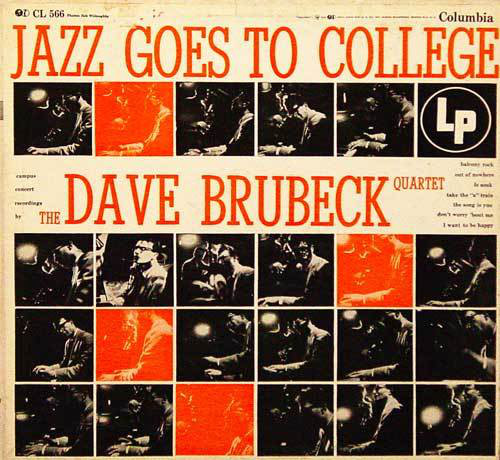

Dave Brubeck beat Duke Ellington onto the cover of Time, a “distinction” that embarrassed him deeply forever after. He was a kind, modest man with a healthy sense of the appropriate, and no part of him thought that he was more deserving of the honor (which was just what it was back then, difficult though it is for us to imagine today) than Ellington. He deserved his fame, though: the original Dave Brubeck Quartet, which he led from 1951 until 1968, was for most of that time one of the world’s most popular jazz groups, and Jazz Goes to College, an immensely successful live album produced by George Avakian and released by Columbia in 1954, made Brubeck a full-fledged star.

Jazz Goes to College was one of the first jazz albums to be widely owned by people who didn’t usually buy jazz albums, my father among them. I found a mint-condition copy in his record cabinet that looked as if it hadn’t been played for a decade, perhaps ever since he’d ordered it from the Columbia Record Club: Jazz Goes to College, an album of cool combo jazz, wasn’t exactly his cup of tea. It suited me right down to the ground, though, and I played it repeatedly, paying increasingly close attention as I did so to the alto saxophone of Paul Desmond, Brubeck’s longtime musical partner.

I wrote about Desmond in The Wall Street Journal when Take Five, Doug Ramsey’s biography, came out in 2005:

You may not know Paul Desmond’s name, but you’ve almost certainly heard his music. He wrote “Take Five,” a sinuous minor-key tune in the once-exotic time signature of 5/4 (marches are in 2/4, waltzes in 3/4, pop songs in 4/4) that was recorded by the Dave Brubeck Quartet in 1959. It shot up the charts a year and a half later, becoming the first jazz instrumental to sell a million copies.

In addition to making its composer rich, “Take Five” introduced the public at large to the inimitable sound of Desmond’s cool-toned, unsentimentally lyrical alto saxophone playing, which he once described as the musical equivalent of a dry martini. In part because of the unexpected popularity of “Take Five,” Brubeck and Desmond became the most famous jazz musicians of the 1960s, and “Time Out,” from which the song was drawn, remains to this day one of jazz’s top-selling albums.

As if being rich and famous weren’t enough, Desmond was also a talented writer of prose (usually in the form of wryly witty liner notes for his solo albums), a ladies’ man (he preferred fashion models, though he made an exception for the young Gloria Steinem) and a seemingly inexhaustible bon vivant (Elaine’s was his after-hours hangout of choice). He also managed to consume far more than his lifetime quota of cigarettes, alcohol and other, more strictly controlled substances, the combined effect of which presumably contributed to his death from lung cancer in 1977….

At a time when so many other saxophonists worked overtime to sound like Charlie Parker, the king of bebop (and a Desmond fan), he went his own soft-spoken way, steering clear of Parker’s searingly fast tempos and jolting broken rhythms. He preferred to stroll through familiar ballads like “Stardust” and “For All We Know,” spinning long, luminous webs of melody subtly tinted with rue. He called himself “the John P. Marquand of the alto,” a sly reference to the author of “Point of No Return” that says as much about Desmond’s impressive cultural literacy as it does about his unappeasable melancholy.

It was Desmond whose playing kept me coming back to Jazz Goes to College. Indeed, I loved it so much that I actually learned how to play the first few choruses of his solo on “Balcony Rock,” the first cut on the album, on violin. Sensing that this was a dead end, I taught myself how to play jazz bass by borrowing a plywood instrument from the band room of the junior high school in Smalltown, U.S.A., and spending the summer plucking along with Bob Bates, the bassist on Jazz Goes to College. A few years later I went off to Kansas City, there to play jazz with other people for the first time in my life.

While I no longer play music—I call myself a “recovering musician,” a joke that really isn’t one—I still listen to Paul Desmond, as well as to Jazz Goes to College, one of the albums of my lost youth that has proved to have the greatest staying power. To hear it now continues to fill me with memories of the far-off days when my ears were first starting to open up to the myriad beauties of jazz.

(To be continued)

* * *

“Balcony Rock,” the first track from Jazz Goes to College. Bob Bates is the bassist, Joe Dodge the drummer:

“Stompin’ for Mili,” a short subject by the Dave Brubeck Quartet filmed by Gjon Mili in 1954. The personnel is the same as is heard on Jazz Goes to College:

* * *

To read about album #1, go here.

To read about album #2, go here.

To read about album #3, go here.

To read about album #4, go here.

To read about album #5, go here.

To read about album #6, go here.

To read about album #7, go here.

To read about album #8, go here.

To read about album #9, go here.

To read about album #10, go here.

To read about album #11, go here.