Various forms of the records-that-changed-my-life meme have been making the rounds lately, so I came up with my own version, which I call “The Twenty-Five Record Albums That Changed My Life.” Throughout the coming month, I’ll write about one of these albums each weekday in the rough order in which I first heard them.

My father, who was born in 1926, loved the popular music of his generation, especially the big bands of the Thirties and Forties (Stan Kenton was his all-time favorite) and the pop singers of the Forties and Fifties (he favored Frank Sinatra, Peggy Lee, and June Christy). He started buying records of his own when he was in high school, and eventually amassed a good-sized collection of 78s, 45s, and long-playing albums, to which I was allowed to listen whenever I liked.

Alas, he started to lose his hearing in the Sixties, and a time came when he no longer listened to music for pleasure save when driving. By then, though, it had become surpassingly clear that I had a not-considerable amount of musical talent, and my parents went well out of their way to make it possible for me to pursue that talent. I started studying violin in the elementary-school music program of Smalltown, U.S.A., in 1966, and from then until I graduated from high school eight years later, I would spend much of my free time playing, listening to, and thinking about music.

It was, of course, classical music that I played on violin, but I’d taken a a shine to jazz and big-band music long before that. While my father wasn’t specifically interested in jazz, he picked up a fair number of full-fledged jazz albums over the years. After $64,000 Jazz, the first one to which I listened regularly and closely was In a Mellotone, an anthology of sixteen extremely well-chosen 78 sides cut by the greatest of Duke Ellington’s bands, the one that he led from 1940 to 1942.Released in 1956, the year of my birth, In a Mellotone featured most of Ellington’s top soloists, including Johnny Hodges on alto saxophone, Tricky Sam Nanton on trombone, Ben Webster on tenor saxophone, and Cootie Williams on trumpet, and it contained several of the Ellington band’s best-remembered compositions, among them “Cotton Tail,” “Main Stem,” “Rumpus in Richmond,” “Perdido,” “A Portrait of Bert Williams,” and the title tune, a medium-tempo swinger that became and has remained a jam-session staple.

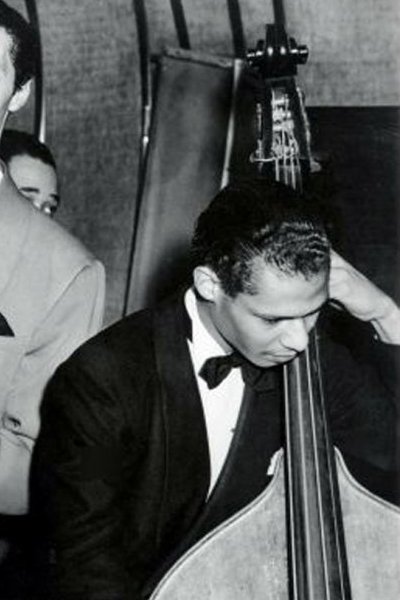

The track that hit me hardest, though, was “Sepia Panorama,” which featured Jimmy Blanton, the first bassist ever to become a major jazz soloist. I had only just started teaching myself how to play that notoriously unwieldy instrument, and Blanton’s slender, penetrating sound and breathtaking technical facility were worlds away from the simple one-and-three bass parts heard on most of the pop and country records played on the radio in those days. I didn’t know anything about Blanton, but I instinctively understood that I wanted to play the way he did, and within a few months I was capable of plucking out a more-than-approximate facsimile of his introductory solo. If anything in particular made me long to be a bass player, it was hearing “Sepia Panorama” at the age of twelve.

Beyond that, what could I possibly have made of the Blanton-Webster band, as this Ellington group is known to jazz aficionados, in 1968? The fact is that I took it for granted. It was, after all, one of countless musical discoveries that I made around that time, and no one in Smalltown knew enough to tell me that Ellington was a genius and In a Mellotone a landmark of American music. I must have assumed that this was what big-band music was supposed to sound like, and it took rather longer for me to understand that the Blanton-Webster band was to jazz what Men Without Women was to short stories.

Even the dullest of dullards finally figured out that the records [Ellington] cut in 1940 were setting a new standard, not just for him but for jazz in general, and today the recordings of what has come to be known as “the Blanton-Webster band” are generally thought to mark the summit of his compositional achievement. Long before his death, that view was enough of a commonplace for Ellington to find it oppressive. “I find I have all these other lifetimes to compete with,” he said. In time he found the competition so irksome that he relegated the Blanton-Webster years to a single sentence in Music Is My Mistress: “During this period—1940-41—we produced some very good music.” He had a point, for the band continued to play on a high level long after Blanton died, just as Ellington continued to write first-rate pieces. But never again would he do so with such consistency, nor would any of his later bands strike so perfect a balance of virtuosity and idiosyncrasy.

That, however, was in 2013. In 1968, I would have been content to assure you that In a Mellotone was a great album and that the guy playing bass on “Sepia Panorama” was…well, I probably wouldn’t have thought to call him a “motherfucker.” At least not yet, that is: I still had a lot to learn.

(To be continued)

* * *

“Sepia Panorama,” composed by Duke Ellington (with the unacknowledged collaboration of Billy Strayhorn) and recorded by the Ellington band in 1940. The bassist is Jimmy Blanton and the tenor saxophonist is Ben Webster:

“Sepia Panorama,” recorded by the Modern Jazz Quartet in 1988. The arrangement is by John Lewis, the group’s pianist, and the bassist is Percy Heath:

* * *

To read about album #1, go here.

To read about album #2, go here.

To read about album #3, go here.

To read about album #4, go here.

To read about album #5, go here.

To read about album #6, go here.

To read about album #7, go here.

To read about album #8, go here.

To read about album #9, go here.